Breaking the chains of pain

Although surrounded by prison walls, razor wire, security and prison guards, the patient cohort that physiotherapist Matthew Beard treated was not that different from those freely walking the city’s streets. If anything, Matthew discovered that incarcerated patients he treated in Adelaide’s jails were grateful to have someone listen.

The idea was simple: start a program for the treatment of prisoners at the prison rather than transporting them to hospital and then run it for a while before passing the program on to another staff member.

The catch? No-one stepped forward to take over the program, so Matthew Beard APAM spent 10 years treating prisoners in Adelaide’s jails.

The program was created to supplant a service that had involved prisoners being escorted to a local hospital for treatment, which posed a security risk

Matthew was involved in introducing a service where clinicians would visit the prison instead. Once established and tested, the program was then extended to all metropolitan Adelaide prisons.

Matthew figured he would pass the reins of the program on to a more junior physio once he got it up and running.

Instead, a decade passed before Matthew moved on—but not from the unforgettable experiences and patients that he met behind bars.

‘Back then I could often be in my prison clinic and have four or five lifers sitting waiting to see me—and there wouldn’t be a prison guard within 100 metres.

'Believe it or not, I never, ever felt unsafe.

'The prisoners were always so appreciative that someone bothered to come out to see them,’ Matthew says.

‘The funny thing is that it was incredibly interesting. I had the chance to hear some remarkable stories—sad and tragic, but some great tales.’

Wearing his professional hat, Matthew would sit and listen as the inmates detailed their medical issues but sometimes the talk

would move beyond the medical to include disclosures about their colourful lives.

He recalls one particular prisoner, who, following an escape, experienced a profound, life-changing injury.

On his return to the correctional facility, rehabilitation became the priority.

This change was driven by a patient who was no longer physically imposing. His future looked different and as a proud First Australian, he sought permission from his Elders to commence traditional painting.

‘At the time the prison authorities weren’t all that enthusiastic about providing paints and canvases [for the inmate], which I thought would be the best form of rehab for him. Far better than anything I’d offer,’ Matthew says.

‘But he was able to acquire paints and materials to paint on.

'He used to bring in his artwork each time I saw him at the clinic and the work was remarkable, really remarkable.

‘My eldest child was very unwell at that time and I let it slip at the time that the only thing that really settled him was watching an ABC program, Bananas in Pyjamas.

'I thought nothing more of it but I knew I probably made an error in divulging some personal matters that weren’t really anything to do with therapy.

'Some months later a package arrived at my office and to my surprise the patient had done a dot painting of B1 and B2 for my son.

'And I tell you what, you never forget that. It was such a touching moment.’

Eventually Matthew moved on from prison work and turned his attention to creating efficiencies within the hospital’s country outreach clinics, which were a costly venture— particularly when they involved flying clinicians out to far-flung locations.

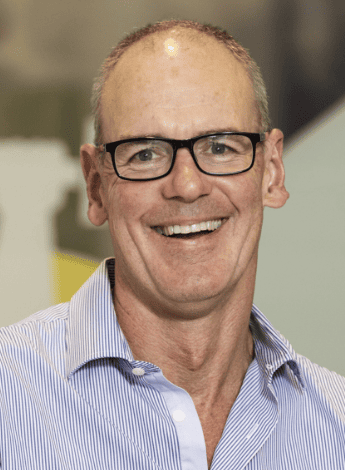

Matthew Beard spent 10 years treating prisoners in Adelaide’s jails.

At the time, SA Health had established a telehealth network, primarily to deliver and support mental health assessments and guardianship reviews.

Taking a look at the technology and realising it was good, Matthew began to inquire about using the videoconferencing for the country outreach clinics but this was initially met with resistance.

‘This was back in 2012 and there were a whole lot of critics who thought that my suggestion was unsafe, that we shouldn’t be considering running clinics remotely,’ Matthew says.

‘But by then the technology had advanced enough. It was really good. It had high bandwidth and the radiology images I could project for the patient were very clear.’

After eventually finding the support he needed, Matthew chose a single site at which to trial the telehealth clinic and then the program was rolled out to GP and community health locations across regional and remote locations.

At that time, there were still people who considered videoconferencing with patients to be a risky endeavour.

However, Matthew was convinced of its value and pushed to highlight the benefits to patients and to the hospital’s bottom line.

‘People said, “Oh, your older patients won’t engage with [telehealth]; they’ll hate it.”

'Well, they don’t; they really like it. We always offer patients the option that if they are uncomfortable with telehealth they can attend the clinic in person.

'I have had maybe a handful of people who requested to come and see us in Adelaide; the remainder were more than happy for our service to be available via videoconferencing.

'Then a COVID-19 pandemic came along and all the critics went quiet. A couple of them even asked me for the protocols of how to set up this kind of service,’ Matthew says.

Long-term vision is something Matthew has developed throughout his physiotherapy career, which started after completing a Bachelor of Science, then honours in neurophysiology, at Adelaide University.

Matthew considered a research career before discovering it wasn’t for him (‘I got fed up spending so much time with mice’). Matthew then went on to complete his physiotherapy degree in the late 1980s, with later postgraduate study to upgrade his skills.

‘Initially I had a dream that I was going to become a sports physio, even though I got my first gig at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

'This was a great opportunity to see many aspects of physiotherapy, across inpatient and rehab settings. And I think that was a very important start,’ Matthew says.

‘You can have ideas, as I did; I was going to become a great sports physio but two things happened.

'One, I wasn’t particularly good at it and two, I didn’t actually like the work.

'Dealing with elite or amateur athletes is sometimes like working in a parallel universe. After a few years, I thought I’d leave it to those who are more gifted and passionate than me.’

Matthew continued to work in the hospital system while also setting up a small private practice within Wakefield House Rheumatology, which he still runs today.

He had the opportunity to act in several management roles before moving into his current position as lead physiotherapist

at the Royal Adelaide Hospital’s Spinal Assessment Clinic.

It is in this advanced practice role that Matthew has discovered his passion for supporting the next generation of physiotherapists and working to keep them in the profession.

‘The elephant in the room for all of us now is the continued loss of many great clinicians early in their career.

'We’ve got numerous universities producing lots of physio graduates but we’re still losing them at a great rate. So why is that?’ Matthew says.

‘There are matters like remuneration and I can’t change that. I think there’s the challenge that for many, regardless of whether they’re in private or public practice, they probably reached their career ceiling at between five and seven years.

'Once they’ve reached that point, I think many of them think, “How long can I stay in this if this is as high as I can go?” I don’t think it matters whether it’s the public or private sector.’

Matthew says it is a complex problem but it is important to take steps to ensure that young physiotherapists are not doing the same tasks day in and day out. There should be variety in their work and what they do well should be celebrated.

‘I’m not just parking these tremendous clinical assets, these amazing staff, in clinic all the time because my concern is that there’s

a potential to burn them out,’ Matthew says.

‘With a changing health landscape, we need to embrace reforms.

'There’s a finite number of patients I can see from now until my retirement—and the same applies to newly minted physios.

'Evolving services that support patients and also staff must be the Holy Grail. Reforms like telehealth, virtual clinics and web-based support tools should be part of the present, not reserved for the future.

‘I believe people have strengths and weaknesses and as a leader I should try to work out what they are. Then I need to try to match their tasks to their strengths and acknowledge success,’ Matthew says.

If there is one thing that Matthew would like to achieve in his career, it is keeping young and gifted physiotherapists in the profession.

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.