Breaking the cycle of repeat fractures

A select group of patients who present with fractures to a hospital in Sydney, New South Wales, is getting help to avoid making the same mistakes again. Melissa Mitchell looks at the success of a new refracture prevention program underway at Liverpool Hospital.

They’re mostly middle-aged women who have slipped, tripped or fallen over and have broken a bone as a result. While not all patients referred to the Osteoporosis Refracture Prevention (ORP) Service at Liverpool Hospital, in Sydney’s south-west, fall into this category, they are by far the majority. And helping them all to take steps to avoid refracturing their injury is the clear objective of this new venture.

The Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI) Musculoskeletal Network and the NSW Falls Prevention Network developed the model of care for osteoporotic refracture prevention. It has been successfully running in various health settings in Australia, and has now been implemented at Liverpool Hospital.

‘Exercise is essential really, as a physio; that’s our mainstream treatment and making sure that patients are taking accountability to improve their condition and feel empowered.’

GLORIA SPRATT, APAM

The program, set up late last year by physiotherapist Julia Gaudin, with Dr Geraldine Hassett and Dr Carlos El-Haddad from the hospital’s rheumatology department, has at-risk patients referred to it from various departments within the facility. Since the program started, more than 100 patients have been invited to be a part of it, and they’re generally patients who have presented to the hospital with a minimal trauma fracture. The patients are identified through the system and assessed for suitability before being invited to join the program.

The hospital’s fracture liaison coordinator (maternity leave), Gloria Spratt, APAM, is a rheumatology physiotherapist and has stepped into Julia’s role to continue coordinating the service to bring potential candidates into the program. Gloria, who has been practising for almost 20 years and who also works in private practice as a hand therapist and Pilates instructor, says she sees the role as a ‘bit of a challenge’ and a great opportunity to upskill. Gloria works with other departments to identify patients who could benefit from the service.

‘I work closely with our rheumatologists and at the same time, when patients are presenting with falls or they’re in our orthopaedics ward, we receive a list indicating patients in the hospital with fractures.

There’s also a system where a list of patients aged over 50 who present to the emergency department with a fracture is emailed to our team weekly. Clinical history is reviewed to see if the injuries classify as a minimal trauma fracture and whether they may be suitable for the ORP service,’ Gloria says.

‘A key role as a fracture liaison coordinator involves identifying patients who have sustained minimal trauma fractures. This requires reviewing the patient’s clinical history and their mechanism of injury. If the fracture was sustained by tripping over or falling from a standing height, that would be classified as a minimal trauma fracture. Fractures sustained via high-velocity incidents, such as a car accident, would not classify as such,’ she says.

Alarmingly, most patients aged over 50 who suffer a minimal trauma fracture have double the risk of refracture within the next 10 years. Many patients are unaware of that fact, and many have been walking around oblivious to the possibility of having reduced bone density or osteoporosis. Gloria says an important part of her role involves educating patients about the risk they face after their initial fracture and advising on effective strategies to prevent refractures.

‘Many of the patients say they didn’t know there was such a high rate of a refracture after their first fracture. Basically, as the name of the service suggests, our purpose is to prevent a refracture because we know of the negative impact it can have on the individual and their family,’ Gloria says. ‘We need to raise awareness of osteoporosis and treatment strategies available to our patients. Improving bone health and fracture prevention can also be achieved through falls risk assessments and initiation of falls prevention strategies. Everyone over the age of 50, or any age for that matter, should engage in exercises involving progressive resistance and balance training. Exercises should be performed regularly and at an adequate intensity. Walking, a common form of exercise for the over 50s, may not be sufficient.’

Refracturing comes at a high cost for the patient and further burdens the healthcare system. For the patient, it can mean an increased risk of hospitalisation and an increased risk in morbidity and mortality rates. Keeping patients who have had one fracture from having another can prevent some patients, mostly the elderly, from experiencing a rapid decline in their health.

In its ‘Model of care for osteoporotic refracture prevention’ 2nd edition, the New South Wales Government and the ACI noted that as many as 50,000 fractures occur every year in the state, and the cost of treating fractures in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory combined is about $740 million. The model notes there is strong evidence to support intervening at the time of the first fracture to prevent the next fracture, and that evidence-based treatment tailored to the individual can lead to a reduced incidence of refracture and a significant cost-saving to the healthcare system.

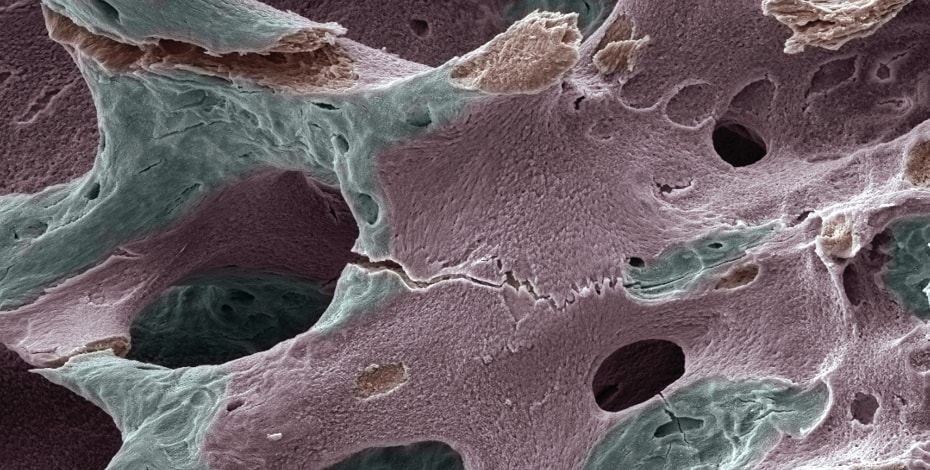

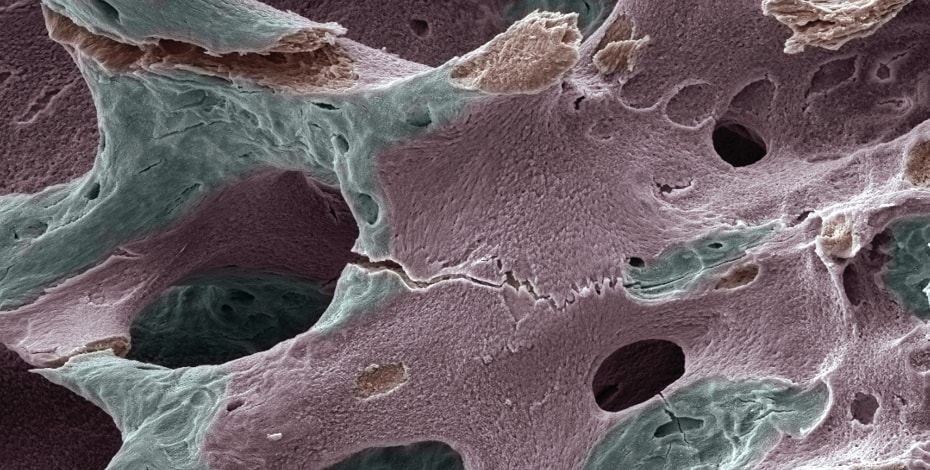

The model reveals that despite the burden osteoporosis and fractures have on society, osteoporosis remains a largely untreated chronic disease. Programs like that being run at Liverpool Hospital aim to identify many of those patients who have undiagnosed osteoporosis. It is estimated that about 4.74 million Australians aged over 50—that’s almost 20 per cent of the population—live with osteoporosis and poor bone health. Gloria says part of the ORP service assessment involves investigations such as a bone mineral density scan, otherwise known as a bone densitometry or DEXA.

‘When the patient presents following a minimal trauma fracture, often times they are women over the age of 50. In that age group, many have had a simple trip on an uneven surface and commonly sustain distal radius, shoulder or hip fractures,’ Gloria says. ‘In the majority of the cases, the patients haven’t had their bone mineral density investigated. So our rheumatologists will organise a DEXA scan to see whether our patients have osteopenia or osteoporosis, and blood tests to determine whether there may be other underlying conditions or factors contributing to the loss of bone density. If indicated, the doctors will start that patient on appropriate medications.’

Part of the service also involves looking at other contributing factors of the fracture such as finding out more about the patient’s lifestyle, their habits, what their nutrition is like, whether they are getting enough time outdoors for vitamin D and whether they are engaging in physical activity or resistance exercises. Gloria says there are many risk factors to consider as part of the individual patient’s treatment plan.

‘Sometimes it’s just the simple things we can implement. It can be getting the patients into our clinic and providing education to start. As part of our assessment we conduct a falls risk assessment and perform a thorough objective examination of the patients. If there are any deficits or impairments, I would prescribe an adequate home exercise program and also encourage them to regularly engage in high-intensity resistance training and balance training as well.

‘Exercise is essential really; as a physio, that’s our mainstream treatment and making sure that patients are taking accountability to improve their condition and feel empowered to optimise their capacity. It’s all about trying to maximise the patient’s physical capacity, their function, strength and mobility,’ Gloria says. ‘We want to empower and encourage patients to stay active and healthy. And, as we know, exercise has immense benefits— mentally, on patients’ brain health, physically, socially and in so many other ways.’

Although the program at Liverpool Hospital is relatively new, Gloria says about 88 per cent of the patients invited to join the program were commenced on pharmaceutical therapy or on osteoporotic medications such as Prolia, a monoclonal antibody used to treat bone loss in women who are at high risk for bone fracture after menopause. She says it is very rewarding work picking up osteoporosis in a patient who has presented with a minimal trauma fracture, as the condition would likely have gone undiagnosed.

‘Osteoporosis can be challenging to manage because it’s essentially a silent condition. Patients usually don’t complain of any pain. In some cases, patients may present with back pain because of a vetebral fracture that they didn’t know was there,’ Gloria says. ‘If they’ve had a fracture they might say “Okay, I’ve broken my hip” and that’s the end of it, not realising that when you’re in that over 50 or the post-menopausal group, bone mineral density reduces and it’s important that we investigate further.

I am really passionate about this role because it’s about educating and increasing awareness in our patients, but more importantly it’s about empowering them to take action with the knowledge they’ve gained to significantly optimise their health and wellbeing.’

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.