Cognitive functional approach to back pain pays off

The results from a large clinical study on the use of cognitive functional therapy to treat people with chronic low back pain have shown that the approach significantly improves outcomes both clinically and from an economic perspective. Peter Kent and Peter O’Sullivan talk about the trial.

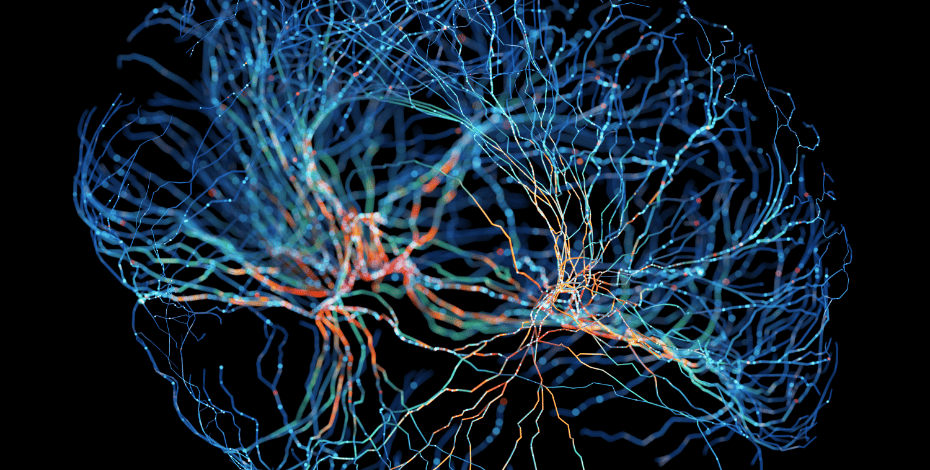

Chronic low back pain (LBP), defined as lasting for three months or more, is the leading cause of years lived with disability globally, due to both persistent pain and high disability.

Around 20–30 per cent of people who have LBP go on to develop chronic LBP and this affects all aspects of their lives.

The societal costs of chronic pain are higher than those of cancer and diabetes combined, mostly due to a loss of work productivity and participation.

Existing treatment approaches for people with LBP are inadequate and LBP-related disability continues to increase.

Part of the problem is that LBP is a complex interaction between biological, physical, lifestyle, psychological, social and cultural factors.

A recently published clinical study compares the relatively new biopsychosocial model of care for chronic LBP—cognitive functional therapy (CFT)—with the usual care that patients typically receive for the condition.

CFT is an individualised approach targeting unhelpful pain-related cognition, emotions and behaviours contributing to pain and disability.

Developed by physiotherapist and Curtin University researcher Professor Peter O’Sullivan APAM FACP, the technique takes a biopsychosocial approach to treating chronic LBP.

‘A common view among both people with pain and clinicians is that chronic back pain means that there’s something damaged in your back and that you need to protect your back and avoid doing things that might hurt you.

'We scan people’s backs and we invariably find stuff. We attribute their symptoms to what is on the scan—you’ve got a degenerative disc or you’ve got disc bulges; therefore, you need to be careful with your back,’ says Peter.

He says that a person’s belief system or mindset about pain can dictate how they respond to chronic pain.

'For example, ‘My pain means I’m damaged; I need to protect it; I need to start avoiding stuff’.

'Patients with chronic LBP become very fearful about engaging in movements and activities, which changes both the body and the nervous system.

'They guard their muscles, moving more slowly and stiffly, in an effort to protect themselves from pain and they start worrying about their back.

'The very behaviours that people use to try to avoid pain end up making the pain worse.

‘CFT explores those factors, explores the person’s beliefs and their emotional responses, the impact that pain has on their life.

'It validates the person, because often they don’t feel validated. It builds rapport and then it explicitly looks at the way the person uses their body in the activities that are painful, that they avoid or that are scary for them,’ Peter explains.

‘You might say to the patient, “You’re holding your body very stiffly and you’re protective when you move.

'Let’s see what happens when we get you to relax and get you to breathe through and engage with those movements that are scary.”

'That’s what we call a process of reframing, making sense of pain by understanding that the pain is not about damage; it’s actually more about your body over-protecting you.’

Through CFT, patients learn how their mindset influences their body’s behaviour and their pain and are taught how to relax their bodies and break the protective reflexes so that they can move and use their bodies again.

Previous small trials of CFT had shown that it could help people with chronic LBP and at least two of the trials demonstrated long-term efficacy.

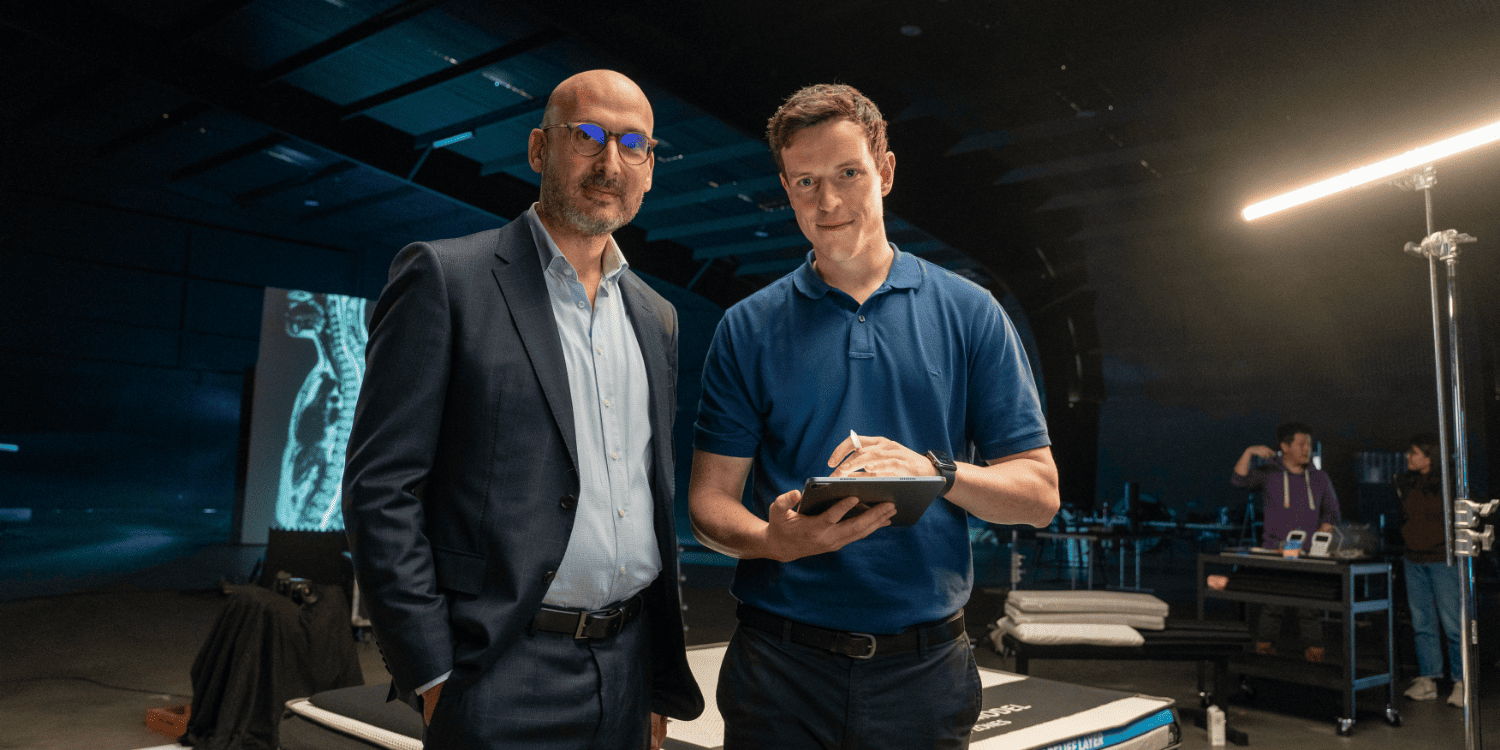

The RESTORE study, a phase 3 randomised controlled trial led by Associate Professor Peter Kent at Curtin University in Perth and Professor Mark Hancock APAM at Macquarie University in Sydney, was designed to look at both clinical outcomes and the economic efficacy of the approach in comparison to usual care.

The study also looked at whether the use of movement sensor biofeedback in combination with CFT was better than CFT alone.

In the trial, 492 participants were randomly assigned to one of the three groups: usual care, CFT or CFT with movement sensor biofeedback.

Participants in the two CFT groups had seven treatment sessions with a physiotherapist trained in CFT over 12 weeks plus a booster session at six months to review and optimise the patient’s self-management plan.

These were longer sessions than is typical (one hour for the initial and 30-40 min for the follow- up appointments).

Both groups wore movement biosensors during the sessions, but clinicians and patients only had access to the biofeedback from the sensors in the CFT with biofeedback group.

All participants were free to seek whatever usual care they preferred during the trial.

Peter O’Sullivan, who was a member of the clinical trial team, says they specifically set out to avoid excluding people from the trial.

‘We included elderly people.

'We didn’t exclude people with mental health challenges or other health comorbidities because we know that chronic, disabling back pain is often comorbid with mental health problems.

'We deliberately wanted to target those patients because we thought the intervention was really well suited to them.

'And we set the criteria so that we didn’t include people with minimal back pain; we wanted people with significant back pain that was disrupting their life,’ Peter says.

‘We found that, compared to other big back pain trials, the people in this trial were generally more disabled.

'We wanted to be very inclusive and capture the people who are really in trouble to see if the intervention helps them. That’s a real strength of this trial.’

Both the clinical effectiveness and the economic efficiency of CFT were compared across the three arms of the study.

The primary clinical outcome was measured using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, a self-test designed to assess physical disability caused by LBP.

Peter O'Sullivan.

This was accompanied by a series of secondary clinical outcome assessments including pain intensity, functional limitation, pain catastrophising, pain self-efficacy, fear of movement and more.

The economic analysis was measured using quality- adjusted life years, taking into account direct and indirect health costs and productivity losses due to an inability to work.

The results of the study were significant.

‘Broadly, there were large and clinically important effects on all the outcomes and those were sustained at 12 months.

'And that’s unusual—not unprecedented, but unusual because what we normally see is a loss of effect.

'Most typically, we see small to moderate effects that are not still there at the 12-month follow-up, but what we saw here was large effects that were sustained and those effects were across all of the outcome measures,’ says Peter Kent.

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire score dropped from an average of about 13.5 (out of 24) to 7.5 for both the CFT and the CFT plus biofeedback groups, when compared to the usual care group, at 13 weeks and this was sustained through to 52 weeks.

This pattern was also seen in the secondary clinical outcomes, which increases the team’s confidence in its results.

The economic outcomes also suggested that CFT, with or without biofeedback, was more effective and much less costly than usual care with savings over $5000 per person over a year.

‘It’s tempting to think that we—or, more accurately, the clinicians who were in the trial—changed something important,’ Peter Kent says.

‘When you look at the relationship between those improvements and quality-adjusted life years and the costs at a societal level, and then put those things together, we see evidence of cost-effectiveness.

Not only was it more effective in terms of quality- adjusted life years, it was also cheaper.

Beyond the direct costs, most of the savings were in participation—that is, the capacity to engage more in paid and unpaid work.

And that’s where the big cost normally is in chronic LBP.’

Surprisingly, there was little difference between the two test arms of the study—the use of the movement sensor biofeedback did not significantly change the CFT results.

While the study team is not sure exactly why, Peter O’Sullivan postulates that it might be because the physiotherapists working with the patients in the CFT only group were addressing each patient’s movement problems effectively, using other forms of feedback such as mirrors, clinician demonstration and video.

While the trial offers the best evidence to date that CFT is an effective approach to treating chronic LBP, there are barriers to implementing it as a preferred model of care.

One of these barriers is the need to train physiotherapists to deliver CFT (see article below).

‘The big question is, can we deliver this in a real-world setting?

'We are looking at ways in which we can support implementation studies to deliver this kind of care at a larger scale. And of course the biggest constraint will be trained mentors to support that,’ Peter says.

Additionally, Peter Kent says, implementing CFT as a preferred model of care has implications from a cost perspective.

A typical CFT session takes about twice as long as the standard 20–30-minute consultation.

‘If you want this quality of care to produce better outcomes at both a societal level and an individual level, we need to re-evaluate the funding model.

Marginally longer consultations can be a cost saving for the community downstream. We need to have a conversation about how we remunerate high-value care,’ he says.

Peter O’Sullivan agrees. ‘We can’t afford to keep doing what we’re doing.

'Through Medicare, we’re paying for $50,000 surgeries, which we know doesn’t work well for many patients with complex presentations, but we fail to spend a thousand dollars on an effective intervention that teaches people to self-manage their condition and reduce reliance on the health system and get them back to work.

‘There’s a strong argument for piloting a change to the funding model to allow people to practise in a different way.’

CFT is likely to have uses beyond the treatment of chronic LBP.

Peter O’Sullivan and his colleagues are looking at the application of CFT to other forms of chronic musculoskeletal pain, including people with knee arthritis and hip pain.

‘We see it as a model of care—it fits with any chronic pain problem. If people are not responding to first-line care, don’t let them go down a dark path of giving in and feeling like there’s no hope.

'This is just an additional, different pathway of care,’ Peter says.

Training physios to deliver CFT

The scale of the trial meant that the trial team needed a large group of physiotherapists trained in CFT to a high level of competence.

In previous trials up to three clinicians provided the CFT, far fewer than the 18 clinicians required for the RESTORE trial.

And those studies had also shown the importance of mentoring the clinicians trained in CFT to enable them to reach the appropriate level of competency and confidence—a weekend of lectures and demonstrations was not enough.

‘You can’t do this in a workshop. You can learn knowledge, but you also need to learn skills and competencies,’ Peter O’Sullivan says.

Before the RESTORE trial could get started, the team trained 18 physiotherapists in Sydney and Perth, a process that took 80 hours over six months.

After the initial training to teach the theory and the skills involved in CFT, the physiotherapists participated in a series of workshops where they each received hands-on instruction and mentoring while working with patients with chronic pain in a group setting.

‘It’s like a learner driver model. One person would be working with the patient and at the beginning we’d be tandem driving with them; we’d be stepping in and coaching them.

'Over time, we slowly stepped back so that they were the driver and while we were still in the passenger seat, we weren’t grabbing the wheel,’ Peter says.

‘One of the key things with the training was a checklist of certain competencies that we expected them to demonstrate when they assessed and treated the patients.

'We filmed each session and gave them personalised feedback based on the checklist so they could go back and see what they missed.’

Because these sessions were performed in a group setting, the physiotherapists were able to see what their fellow trainees did with their patients, further reinforcing the learning process.

At the end of the training, the physiotherapists completed a competency assessment in front of the research team’s trainers.

Peter Kent.

Peter Kent says that qualitative analysis of interviews with the clinicians during the training process has signalled that the one-on-one mentoring was critical to developing competence and confidence in CFT and so was the support provided by training the clinicians in groups.

‘Our trainees described that training journey as paralleling the patient journey in the sense that they also were going through a kind of behavioural modification approach,’ he says.

Peter O’Sullivan says the next step will be to help more physiotherapists upskill so they can deliver CFT as part of their care for people with LBP.

'We have a number of follow-up implementation studies running where groups of people in different parts of the world have said, we want to train our group to do this,’ Peter says.

‘We are thinking the best way is to train communities of practice—that’s the most sustainable model going forward.'

>> Click here for more information about the RESTORE trial. And for an infographic summarising the key results of the study, click here.

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.