Complex emotional distress and severe, persistent non-specific abdominal pain

Emotional distress has a bi-directional relationship with pain. Here is a case of a middle aged Aboriginal woman who presented with a nine-year history of worsening abdominal pain after surgery, was effectively bedridden, and had been experiencing worsening pain-related fainting.

Psychological distress is a state of emotional suffering characterised by symptoms of depression and anxiety, affecting between five to 27 per cent of the general population (Drapea et al 2012).

Individuals with persistent pain are three to 16 times more likely to report high levels of psychological distress than those without pain (Blyth et al 2001).

Conversely, people with high psychological distress are also more likely to report persistent pain with the likelihood of disabling pain among people who are depressed 6.7 times that of those who are not, and anxiety 4.8 times (de Heer et al 2014).

Depression and anxiety commonly co-exist, and the risk of persistent disabling pain increases dramatically among individuals with both depression and anxiety (30.3 times; de Heer et al 2014).

Higher levels of psychological distress are associated with higher levels of pain and disability (Dominick et al 2012, Gerrits et al 2012, Lerman et al 2015).

Several mechanisms could underlie the relationship between pain and psychological distress.

From a neurobiological perspective, pain and psychological distress share common cortical regions, neurobiological networks and neurochemistry (Lerman et al 2015).

Both anxiety and persistent pain are associated with downregulation of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline, key neurochemicals involved in descending pain modulation (Lerman et al 2015, Lucchetti et al 2012).

Psychological distress, in particular co-existing anxiety and depression, is reported to increase pain via chronic inflammation, due to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis and impaired immune system function (Camacho 2013).

From a cognitive standpoint, psychological distress is associated with more negative cognitive bias and increased catastrophic worry about pain (Lerman et al 2015).

Behaviourally, individuals who are anxious or depressed may also be less motivated to engage in self-management.

Major risk factors for psychological distress include being female (twice as likely), having parent(s) with anxiety/depression, and adverse childhood experiences such as physical and/or sexual abuse (Craske et al 2017).

In particular, traumatic experiences in childhood and throughout the lifespan are strongly associated with future emotional distress and pain (Sachs-Ericsson et al 2017).

From a physiotherapy management perspective, providing high-value, person-centred care for individuals with severe emotional distress and disabling pain requires an understanding of the psychological processes, integrating these into care, and, often, working successfully with an inter-professional health team.

This article reports the case of ‘Tamsin’, a 52-year old Aboriginal woman living in a rural town, who has severe, disabling abdominal pain closely linked to emotional distress.

Her case is reported due to the unusual, severe, debilitating nature of the symptoms that include severe functional loss and regular episodes of fainting in response to pain.

Treatment is continuing, so this case report describes Tamsin’s early presentation, examines the hypothesised determinants and contributing factors, and outlines considerations in ongoing psychologically informed management.

History

Tamsin presented with a nine-year history of predominantly right-sided abdominal pain following emergency abdominal surgery to remove her gall bladder.

Due to postoperative complications, Tamsin spent six weeks in a metropolitan hospital, describing her experience as ‘traumatic’ and ‘horrible’. She had persisting mild abdominal pain following discharge.

Later that year she and her husband travelled around Australia during which time Tamsin resumed part-time work as a kindergarten teacher. She reported markedly worsening abdominal pain while working, and was unable to continue, increasing her anxiety.

She believed there was an ongoing internal abdominal problem and something hadn’t healed after surgery. Because of worsening pain, Tamsin returned home to Western Australia for medical care.

Over the next five years Tamsin underwent multiple investigations (exploratory surgery, endoscopy, colonoscopy, ultrasound, MRI) and no medical explanation for her pain was identified.

She was eventually diagnosed with ‘chronic pain’, although she did not know what this meant. Eighteen months ago she began fainting in response to pain, often when going out for medical appointments. Medical investigations were not able to identify a cause.

Tamsin had not been able to work and 15 months ago her husband gave up his work as a mechanic to become her carer.

In February 2020 Tamsin underwent an abdominal MRI with contrast. She described this experience as very distressing because her husband was not allowed to accompany her and the nurse who inserted the cannula was very ‘rough’.

Following this, her anxiety and pain increased substantially. Since February she had been out of bed only for personal care (toileting and showering) and once to visit a family member.

Tamsin was referred in April 2020 and seen on a home visit in June 2020.

She described constant right-side abdominal pain (six to eight out of 10 on numerical rating scale) spreading around her abdomen to her back, and had fainted 10–12 times in the previous week.

Her pain was aggravated getting out of bed. Her husband assisted her to shower (past six months) and toilet (past four months). Eating a big meal triggered reflux and pain.

Her sleeping pattern revolved around her pain and medications. She slept poorly for four hours after medications at 9pm, two hours after medications at 6am, and two hours after medications 10am. She avoided touching her right abdomen due to pain.

Tamsin’s reported poor mental health, describing anxiety, depression, high levels of family-related stress and post-traumatic stress disorder having experienced ‘trauma her whole life’. She requested not to talk about childhood trauma events.

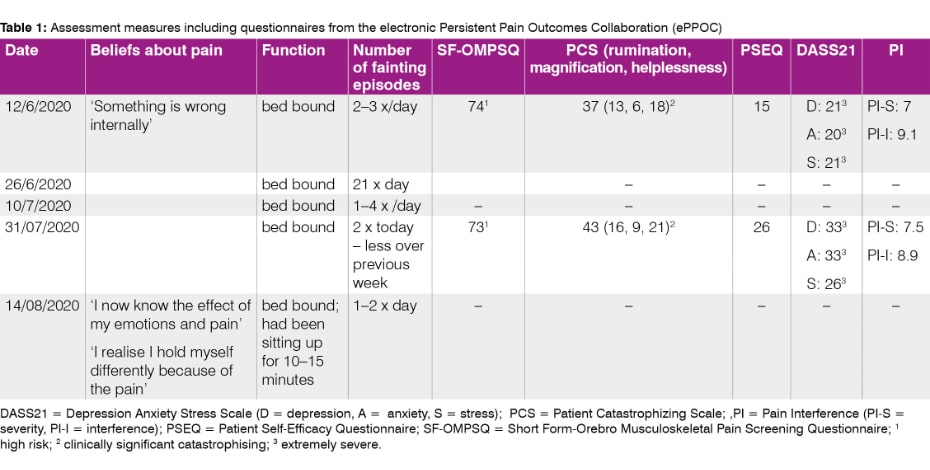

Tamsin had recently started seeing a clinical psychologist (two visits). Pain interference, emotional distress, catastrophising, and self-efficacy, assessed using outcomes from the electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration (ePPOC), placed her in severe/high risk categories.

She was asthmatic, experienced tension headaches, strong period pain, reflux, and was intolerant to lactose, oil and some animal fats.

She was taking medications for these in addition to a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (duloxetine 60 mg) for depression/anxiety.

Tamsin was taking opioid medications (Palexia SR, Temgesic, Palexia) equal to 197 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and Pregabalin (75 mg/day). When her pain was worse she described her abdomen as tight and her breathing ‘working against her tummy’.

Tamsin was fearful of physiotherapy and the possible effect on her pain. On the recommendation of her GP, three weeks prior to when first seen, she had commenced an online chronic pain management program.

She reported that this was the first time she had become aware of the link between emotions and pain. Her primary goals were to visit a new grandchild in northern Western Australia, and to cook and garden again.

Clinical examination

When examined, Tamsin was lying supine in her darkened bedroom with three pillows and a flexed neck.

On clinical sensory testing (CST; Beales et al 2020) sharp and cold hyperalgesia were noted in the right abdomen, around the surgical scar.

When undertaking a ‘body scan’ Tamsin reported that her right abdomen felt like a ‘lump’ and was difficult to visualise.

Directing her attention to this region increased her pain. This was associated with increased respiratory rate and trembling of her left foot. Temporal summation and pressure palpation were not assessed because of patient irritability.

Active straight leg raise was effortful and increased her abdominal pain, with elevated respiratory rate and contraction of her abdominal muscles.

Pain reduced with guided, relaxed diaphragm breathing. Visualising her leg as light ‘balloons lifting your leg’ reduced the heaviness sensation. Left leg lift was not painful, nor felt heavy.

Left shoulder flexion was pain-free (150 degrees—able to touch the wall behind her head). Right shoulder flexion (in supine) was painful in her abdomen and limited (120 degrees).

Following guided relaxed diaphragm breathing and gentle repeated flexion, her shoulder movement increased to 150 degrees.

Removing one pillow (less neck flexion) resulted in an elevated respiratory rate, increased abdominal pain, twitching/ shaking in the face and legs, and a fainting sensation.

This reduced when the pillow was returned and with guided diaphragm breathing. Turning her head repeatedly to look to the right was more effortful and painful. Attending to a task on her right side, ‘how many fingers am I holding up?’, was slower and less accurate than the left.

Further functional movements such as rolling and getting out of bed were not attempted.

Clinical reasoning

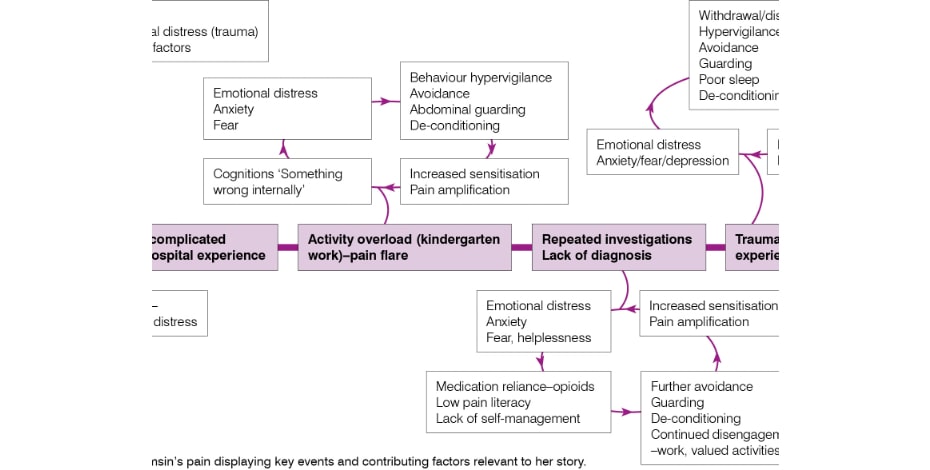

Interpretation considered the multidimensional factors contributing to Tamsin’s condition (Mitchell et al 2017).

The diagnosis was persistent, severe, non-specific abdominal pain. Central to her presentation was the relationship of pain and emotional distress.

Episodes of fainting were hypothesised to be a form of psychological escape triggered by pain and strong emotions such as fear, distress and panic (Buodo et al 2012).

This response could be a dissociative response, a common feature of complex trauma, and is a protective coping mechanism (Kezekman & Sarvopoulos 2019).

Tamsin’s pain and emotional distress were entwined with other contributing factors, including the belief that she had something wrong internally, low levels of pain literacy, and a high sensitivity suggesting nociplastic pain and central sensitisation.

She was highly fearful of movement and its effect on her pain. Tamsin utilised unhelpful guarding behaviours of her trunk muscles, associated with pain-related anxiety and fear, which worsened her pain.

Tamsin appeared to be physically de-conditioned. The interpretation of Tamsin’s pain is detailed as a timeline of key events and contributing factors relevant to her story.

Management

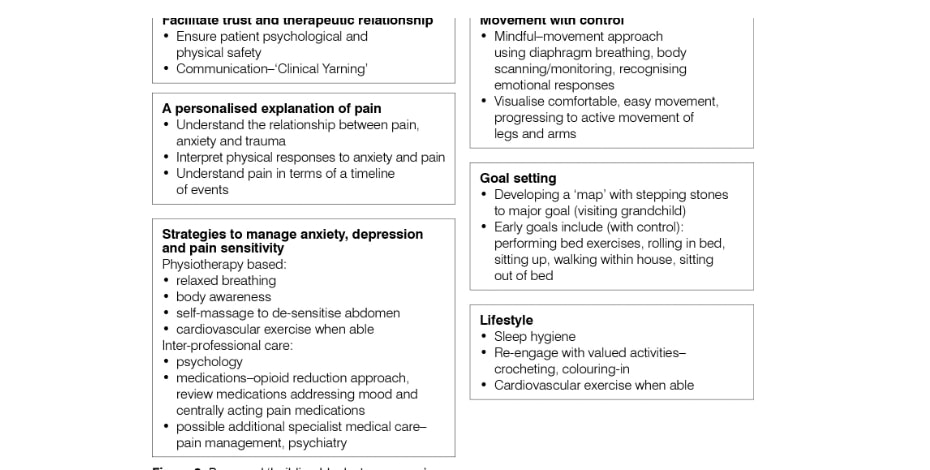

Management was guided by complex trauma-informed practice (Kezelman & Stavropoulos 2019).

A deliberate focus was given to developing trust and the relationship with Tamsin, utilising a clinical yarning style of communication (Lin et al 2016), listening carefully to her story with empathy, and being aware of cues indicating overt distress.

Guidelines for complex trauma emphasise the importance of physical and psychological safety and keeping within a ‘window of tolerance’ (Kezelman & Stavropoulos 2019).

Episodes of fainting were interpreted as a marker of distress and an unhelpful maladaptive behaviour, and avoided where possible.

Management involved an explanation, based on her story, to enable her to make sense of her pain (Bunzli et at 2017).

Conscious diaphragm breathing and body scanning were introduced as a strategy for trunk muscle relaxation, to reduce over-arousal and to increase mind–body awareness.

This was also combined with visualising movements of her arms and legs (hip flexion, straight leg raises, arm elevation/ reaching across her body), progressed to active movements provided pain and signs of pain/distress (increasing breathing and abdominal muscle contraction) did not increase.

Turning her head to the right and attending to activities to her right, such as her husband talking to her on her right side, were recommended.

Gentle self-massage around her scar was encouraged within tolerance as a de-sensitising strategy. The benefits and safety of movement and touch were emphasised, related back to her pain story.

Collaborative goal-setting worked backwards from Tamsin’s primary long-term goal to travel to visit her granddaughter (one to two days via car).

Initial goals were to do her arm and leg exercises as above, practise rolling on her side and sitting on the edge of her bed when it was not essential (eg, for toileting) for 10 seconds.

Steps towards her goals were mapped out (eg, sitting, standing, walking). She was encouraged to re-engage with enjoyable activities she had been avoiding, including colouring-in and crocheting.

Her GP and psychologist were emailed to inform them of the planned physiotherapy approach and to invite a case discussion.

Progress to date

To date Tamsin has been seen for five home visits and three phone call discussions over nine weeks. During this time, she has experienced the deaths of three family members and high levels of family-related stress that she identifies as increasing her pain.

She has fainted twice during physiotherapy. Most recently, Tamsin reported that she had begun sitting on the edge of her bed for up to 15 minutes, the first time for non-essential reasons in seven months.

ePPOC follow-up questionnaires were repeated at six-weeks, coinciding with a period of elevated pain and distress. Pain interference, catastrophising, emotional distress and the SF-OMSPQ scored similarly or poorly compared to previous.

The exception was pain self-efficacy (increased from 15 to 26) exceeding a minimally important change of 5.5 points (Chiarotto et al 2016).

Her beliefs about the cause of her pain had shifted from ‘something still wrong inside’, to beliefs more aligned with contemporary, biopsychosocial understandings.

In low back pain, changes in an individual’s schema about their pain, including their beliefs, expectations and meaning of a stimulus, are believed to underlie shifts in the construct of their pain, resultant pain- related behaviours, and disability (Caneiro et al 2019).

In Tamsin’s case, changes in her beliefs and self-efficacy are some of the proposed ‘building blocks to change’, and appear related to early positive signs of progress.

Discussion

This report documents the assessment, interpretation and management of a client with severe, disabling abdominal pain linked strongly to complex emotional distress.

Physiotherapy management to date has been cautious, due to her regular fainting. Functional assessment has been limited.

The rationale of adopting a slow, cautious approach was taken because of Tamsin’s fear of physiotherapy, the need to ensure client physical and psychological safety (Kezelman & Stavropoulos 2019), the time required to develop trust and a strong therapeutic relationship, and to avoid aggravating pain given her high levels of pain sensitivity (Beales et al 2020).

Despite this caution, she has fainted at two physiotherapy appointments.

Reorienting patient beliefs about pain, and then confronting feared tasks with strategies to control pain, that is, exposure with control, can be a powerful catalyst to behavioural change and improvements in disability (Nijs et al 2015, O’Sulliivan et al 2018).

At this stage, control of pain is lacking and arguably a barrier to progression.

A number of ‘building blocks to recovery’ for Tamsin have been proposed. Addressing these building blocks requires integrated multidisciplinary care, for areas outside of the scope of physiotherapy.

A key element of pain control is pharmacological management. Currently there is a strong reliance on opioid medications, equivalent to 197 MME/day.

This is substantially higher than the threshold recommended by clinical guidelines of 90 MME/day (Dowell et al 2016).

Potential risks include dependence, overdose, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia (Dowell et al 2016). Although definitive evidence is lacking, first-line medications for nociplastic pain are triclyc antidepressants (Finnerup et al 2015), which may also reduce depression and improve sleep.

A review of pharmacological management for emotional distress may also be warranted.

Physiotherapy exercise management is focusing on mindful, body-aware movements, and control of autonomic responses (eg, through breathing).

In addition to benefits on pain, mind–body approaches are reported to improve emotional distress by assisting individuals to disentangle and better regulate physical, cognitive and emotional input (van de Kamp et all 219, Van der Colo et al 2014).

Progressing to more challenging functional tasks is a priority once there is more stable control of pain. Graded motor imagery is another mind–body approach (Moseley 2012) and tasks such as left/right discrimination may be helpful if movement is too irritable.

Once able, commencing cardiovascular exercise is a priority to enhance pain management, physical and mental health (Daenen et al 2015).

Integrated multidisciplinary pain management is often provided by specialty pain management services. However, in rural areas where Tamsin lives, accessibility to such services is low, and may be further reduced for Aboriginal Australians (Lin et al 2018, National Pain Summit Initiative 2010).

Despite willingness from the health professionals involved in her care (GP, psychologist and physiotherapist), integrating care has been challenging, possibly because practitioners are time poor, funding models do not support integrated pain care by primary care providers, and services are not co-located.

After some challenges, the involved practitioners have scheduled a case meeting to better integrate care approaches.

Conclusion

Severe disabling pain and complex emotional distress requires multidisciplinary care. Physiotherapy addressing underlying unhelpful beliefs and using mind–body approaches can benefit both physical and psychological contributing factors.

However, unless all ‘building blocks’ to recovery are addressed, resolution may be challenging.

- References

[1] Beales D, Mitchell T, Moloney N, Rabey M, Ng W, Rebbeck T. Masterclass: A pragmatic approach to pain sensitivity in people with musculoskeletal disorders and implications for clinical management for musculoskeletal clinicians. Musculoskeletal science & practice 2020:102221.

[2] Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJM, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain 2001;89(2–3):127-134.

[3] Bunzli S, Smith A, Schütze R, Lin I, O’Sullivan P. Making Sense of Low Back Pain and Pain-Related Fear. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017(0):1-27.

[4] Buodo G, Sarlo M, Poli S, Giada F, Madalosso M, Rossi C, Palomba D. Emotional anticipation rather than processing is altered in patients with vasovagal syncope. Clin Neurophysiol 2012;123(7):1319-1327.

[5] Camacho Á. Is anxious-depression an inflammatory state? Med Hypotheses 2013;81(4):577-581.

[6] Caneiro J, Smith A, Linton SJ, Moseley GL, O'Sullivan P. ‘How does change unfold?’an evaluation of the process of change in four people with chronic low back pain and high pain-related fear managed with Cognitive Functional Therapy: A replicated single-case experimental design study. Behav Res Ther 2019.

[7] Chiarotto A, Vanti C, Cedraschi C, Ferrari S, Resende FdLeS, Ostelo RW, Pillastrini P. Responsiveness and minimal important change of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire and short forms in patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain 2016;17(6):707-718.

[8] Craske MG, Stein MB, Eley TC, Milad MR, Holmes A, Rapee RM, Wittchen H-U. Anxiety disorders. Nature reviews Disease primers 2017;3(1):17024.

[9] Daenen L, Varkey E, Kellmann M, Nijs J. Exercise, not to exercise, or how to exercise in patients with chronic pain? Applying science to practice. The Clinical journal of pain 2015;31(2):108-114.

[10] de Heer EW, Gerrits MMJG, Beekman ATF, Dekker J, van Marwijk HWJ, de Waal MWM, Spinhoven P, Penninx BWJH, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. The Association of Depression and Anxiety with Pain: A Study from NESDA. PLoS ONE 2014;9(10):e106907.

[11] Dominick CH, Blyth FM, Nicholas MK. Unpacking the burden: Understanding the relationships between chronic pain and comorbidity in the general population. Pain (Amsterdam) 2012;153(2):293-304.

[12] Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315(15):1624-1645.

[13] Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. Epidemiology of Psychological Distress, Mental Illnesses-Understanding, Prediction and Control, Prof. Luciano LAbate (Ed.), InTech, DOI: 10.5772/30872, 2012.

[14] Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Neurology 2015;14(2):162-173.

[15] Gerrits MMJG, Vogelzangs N, van Oppen P, van Marwijk HWJ, van der Horst H, Penninx BWJH. Impact of pain on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Pain 2012;153(2):429-436.

[16] Kezelman C, Stavropoulos P. Practice guidelines for clinical treatment of complex trauma. Sydney: Adults Surviving Child Abuse. Milsons Point: Blue Knot Foundation, 2019.

[17] Lerman SF, Rudich Z, Brill S, Shalev H, Shahar G. Longitudinal Associations Between Depression, Anxiety, Pain, and Pain-Related Disability in Chronic Pain Patients. Psychosom Med 2015;77(3):333-341.

[18] Lin I, Green C, Bessarab D. ‘Yarn with me’: applying clinical yarning to improve clinician–patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Aust J Prim Health 2016;22(5):377-382.

[19] Lin IB, Bunzli S, Mak DB, Green C, Goucke R, Coffin J, O'Sullivan PB. Unmet Needs of Aboriginal Australians With Musculoskeletal Pain: A Mixed‐Method Systematic Review. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70(9):1335-1347.

[20] Lucchetti G, Oliveira AB, Mercante JPP, Peres MFP. Anxiety and fear-avoidance in musculoskeletal pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16(5):399-406.

[21] Mitchell T, Beales D, Slater H, O'Sullivan P. Musculoskeletal clinical translation framework: from knowing to doing, 2017.

[22] Moseley GL. The graded motor imagery handbook: Noigroup publications, 2012.

[23] National Pain Summit Initiative. National pain strategy: pain management for all Australians Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian Pain Society and Chronic Pain Australia, 2010.

[24] Nijs J, Lluch Girbés E, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Man Ther 2015;20(1):216-220.

[25] O'Sullivan P, Caneiro J, O'Keeffe M. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain (vol 98, pg 408, 2018). Phys Ther 2018;98(10):903-903.

[26] Sachs-Ericsson NJ, Sheffler JL, Stanley IH, Piazza JR, Preacher KJ. When Emotional Pain Becomes Physical: Adverse Childhood Experiences, Pain, and the Role of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. J Clin Psychol 2017;73(10):1403-1428.

[27] van de Kamp MM, Scheffers M, Hatzmann J, Emck C, Cuijpers P, Beek PJ. Body‐and Movement‐Oriented Interventions for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. J Trauma Stress 2019;32(6):967-976.

[28] Van der Kolk BA, Stone L, West J, Rhodes A, Emerson D, Suvak M, Spinazzola J. Original research yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75(6):e559-e565.

Ivan Lin is a musculoskeletal registrar undertaking Fellowship of the Australian College of Physiotherapists by Clinical Specialisation. Ivan works on Yamaji country as a clinician with the Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service, is a researcher and senior lecturer with the Western Australian Centre for Rural Health (University of Western Australia), and is adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the Curtin University School of Physiotherapy and Exercise Science.

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.