Five facts about … osteoarthritis

Joanne Kemp, Christian Barton, Allison Ezzat, Danilo de Oliveira Silva, Joshua Heerey and Marcella Ferraz Pazzinatto present five discussion points about the role of physiotherapy in the diagnosis and management of osteoarthritis.

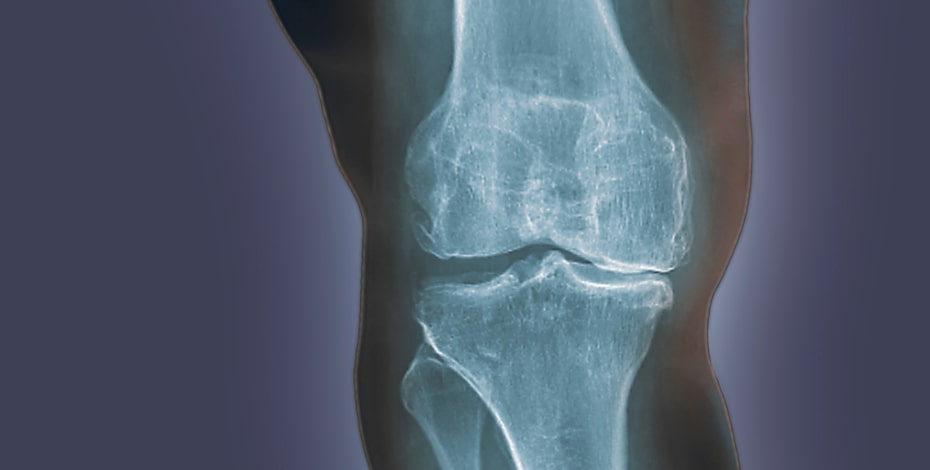

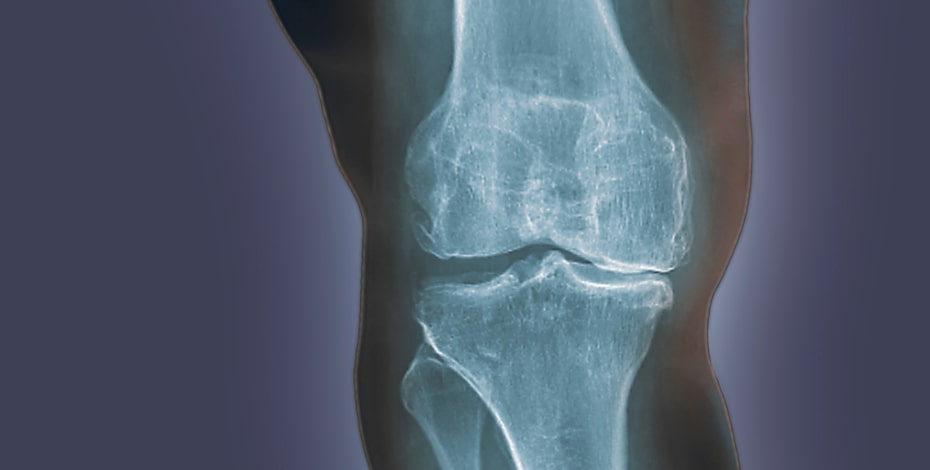

1. Imaging is not required to diagnose osteoarthritis

Guidelines endorse the use of clinical criteria for diagnosing osteoarthritis without the need for imaging (RACGP 2018).

Imaging should only be considered when a person has an atypical presentation, such as a history of joint trauma, rapid worsening of symptoms, evidence of a hot swollen joint or other potential red flags (RACGP 2018).

Physiotherapists need to understand the imprecise relationship between features of osteoarthritis on imaging and symptoms, especially with the increasing prevalence of structural osteoarthritis with ageing (Pereira et al 2011, Kim et al 2015).

Physiotherapists should conduct a comprehensive subjective and physical examination in a person with osteoarthritis.

It is important that the physiotherapist understands how osteoarthritis affects the individual’s function (including physical activity), quality of life, relationships (personal and professional), sleep, medication use and any other relevant medical conditions (RACGP, 2018).

This approach provides the physiotherapist with an understanding of the impact that osteoarthritis has on the person as a whole and allows for the provision of holistic, patient-centred care.

2. Joint structural damage does not fully explain osteoarthritis pain

Osteoarthritis symptoms can occur before any structural changes appear on imaging.

This highlights that pain is not necessarily a ‘message’ from a damaged joint, but a complex experience associated with memories, emotions, beliefs, and social context. Many factors play a role determining whether a person will perceive a stimulus as painful or not.

A large proportion of people with osteoarthritis present manifestations of peripheral and central sensitisation (eg, pressure hyperalgesia, impaired conditioning modulation, etc.), which have been linked to poorer clinical outcomes and prognosis (De Oliveira Silva et al 2019).

Additionally, psychological impairments including anxiety, depression, fear of movement, and pain catastrophising are associated with disability and pain flares in people with osteoarthritis (Wise et al 2009).

If physiotherapists focus less on imaging and more on the biopsychosocial factors related to each person’s pain and disability, opportunities for multidisciplinary collaboration and improved treatment outcomes will be created.

3. Exercise is safe and recommended for osteoarthritis

Exercise therapy is recommended by all guidelines as a first line intervention for osteoarthritis.

The incorrect belief that exercise may harm the joint cartilage is common among people with osteoarthritis and physiotherapists managing the condition.

Findings from two recent systematic reviews (Bricca et al 2019a, Bricca et al 2019b), including more than 1700 participants, suggest that exercise therapy does not trigger inflammatory reactions nor harm articular cartilage in people with osteoarthritis.

There is evidence that exercise therapy can improve cartilage matrix content in people who were at high risk of osteoarthritis (Roos & Dahlberg 2005).

Exercise therapy can also strengthen muscles, improve joint stability, and increase range of motion.

Therefore, instead of rest, people with osteoarthritis should be encouraged and supported to engage with exercise and physical activity, which is essential for good joint and general health.

Physical activity and exercise are essential to the prevention of at least 35 chronic diseases (Skou et al 2018), many of which are common in people with osteoarthritis.

4. Osteoarthritis can be prevented by managing modifiable risk factors

Strong evidence suggests that osteoarthritis can be prevented by addressing key modifiable risk factors (Whittaker et al 2019).

Traumatic joint injuries (usually during sport or exercise activities) are one of the strongest risk factors for osteoarthritis development, with one in two people developing osteoarthritis in the following decade.

However, injury prevention programs (eg, FIFA-11+, Prep to Play) can successfully prevent up to 67 per cent of sport-related injuries (Webster et al 2018).

Obesity is another well-established risk factor, contributing to osteoarthritis development in two distinct ways.

Mechanically, excess body weight results in increased mechanical loading to all joint structures.

Systemically, obesity-related metabolic factors contribute to osteoarthritis by inducing pro-inflammatory processes in cartilage and bone (Wang et al 2015).

Maintaining a healthy body weight is a strategy to both prevent the development and reduce the symptoms of osteoarthritis.

Excessive occupational load, physical inactivity, and muscle weakness have all been linked to osteoarthritis development.

Highly physical jobs involving large amounts of kneeling or lifting (eg, construction workers) may increase a person’s risk of osteoarthritis.

Physical activity is essential for joint health, stimulating cartilage regeneration. Muscle strengthening both in isolation and in functional tasks can reduce the odds of developing osteoarthritis and improve symptoms.

These modifiable osteoarthritis risk factors provide numerous opportunities for evidence-based strategies to prevent and manage this disease.

5. Surgery should not be the first treatment choice for patients with osteoarthritis

Many people believe the only way ‘to fix’ osteoarthritis is surgery.

Current evidence suggests that knee arthroscopic surgery is no better than other non-surgical interventions (ie, exercise therapy, injections), or even sham surgery, for people with symptomatic mild to moderate osteoarthritis (Palmer et al 2019, Moseley et al 2002).

Many people with severe osteoarthritis do get significant pain relief from joint replacement surgery.

However, up to one in five people with knee osteoarthritis who undergo this procedure are not satisfied with the outcome, with 30 per cent still presenting symptoms such as pain, stiffness, and difficulty in daily activities after surgery (Bourne et al 2010).

Approximately, seven per cent of people with hip osteoarthritis are dissatisfied with the outcome, having worse quality of life at one year after the total hip arthroplasty compared to before surgery (Anakwe et al 2011).

Surgery should only be considered after attempting high-value non-surgical care that includes exercise therapy, education, and weight management (if needed) (Bannuru et al 2019).

Click here for an infographic poster version of this article.

Associate Professor Joanne Kemp is a titled APA Sports and Exercise Physiotherapist and senior research fellow at the Latrobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. She is co-project lead for GLA:D® Australia with an interest in non-surgical, exercise-based interventions to slow the progression and reduce symptoms associated with hip pain and osteoarthritis.

Associate Professor Christian Barton is a physiotherapist and a current MRFF Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP), based at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. He is the co- lead of the GLA:D® Australia Program and leads education through the Translating Research Evidence and Knowledge (TREK) initiative.

Dr Allison Ezzat is a physiotherapist and postdoctoral fellow at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. Allison holds a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship. Her research focuses on using process evaluation and implementation science to advance the prevention of knee injuries and non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis.

Dr Danilo de Oliveira Silva is a physiotherapist, post-doctoral research fellow at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. His research focuses on understanding the integration among biomechanics, pain characteristics and psychological aspects associated with patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis. Danilo is the development director of the Translating Research Evidence and Knowledge (TREK) initiative.

Joshua Heerey is a physiotherapist and research fellow at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. His research has involved exploring the relationship between imaging findings of the hip joint and pain, and identifying risk factors for early hip osteoarthritis in young athletes.

Dr Marcella Ferraz Pazzinatto is a physiotherapist and research fellow at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre. Her research is focused on the assessment and management of persistent knee pain.

- References

Fact 1 References:

1. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2nd edn. East Melbourne: Vic: RACGP, 2018

2. Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araujo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(11):1270–85.

3. Kim C, Nevitt MC, Niu J, Clancy MM, Lane NE, Link TM, et al. Association of hip pain with radiographic evidence of hip osteoarthritis: diagnostic test study. The BMJ. 2015;351:h5983.

4. Altman, R., Asch, E., Bloch, D., Bole, G., Borenstein, D., Brandt, K., ... & Wolfe, F. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1986;29(8), 1039-1049.

5. Altman, R., Alarcon, G., Appelrouth, D., Bloch, D., Borenstein, D., Brandt, K., ... & Wolfe, F. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1991;34(5), 505-514

Fact 2 References:

1. De Oliveira Silva D, Rathleff MS, Petersen K, Azevedo FM de, Barton CJ. Manifestations of pain sensitization across different painful knee disorders: A systematic review including meta-analysis and metaregression. Pain Med. 2019;20(2):335-358. doi:10.1093/pm/pny177

2. Wise B, Niu J, Zhang Y, Wang N, Jordan J, Choy E, Hunter DJ. Psychological factor and their relation to osteoarthritis pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010, 18(7):883-887. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2009.11.016

Fact 3 References:

1. Bricca A, Struglics A, Larsson S, Steultjens M, Juhl CB, Roos EM. Impact of exercise therapy on molecular biomarkers related to cartilage and inflammation in individuals at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(11):1504-1515. doi:10.1002/acr.23786

2. Bricca A, Juhl CB, Steultjens M, Wirth W, Roos EM. Impact of exercise on articular cartilage in people at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(15):940-947. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098661

3. Roos EM, Dahlberg L. Positive effects of moderate exercise on glycosaminoglycan content in knee cartilage: A four-month, randomized, controlled trial in patients at risk of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3507-3514. doi:10.1002/art.21415

4. Skou ST, Pedersen BK, Abbott JH, Patterson B, Barton C. Physical activity and exercise therapy benefit more than just symptoms and impairments in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(6):439-447. doi:10.2519/jospt.2018.7877

Fact 4 References:

1. Whittaker J, Roos E. A pragmatic approach to prevent post-traumatic osteoarthritis after sport or exercise related joint injury. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(1):158–71.

2. Webster et al. Meta-analysis of meta-analyses of ACL injury reduction programs. J Orthop Res 2018

3. Wang X, Hunter D, Xu J, Ding C. Metabolic triggered inflammation in osteoarthritis. 2015; 23(1); 22-30.

Fact 5 References:

1. Palmer JS, Monk AP, Hopewell S, Bayliss LE, Jackson W, Beard DJ, Price AJ. Surgical interventions for symptomatic mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012128.pub2.

2. Moseley B. et al, A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine. Vol 347 (2) 2002.

3. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 468:57–63, 2010.

4. Anakwe RE, Jenkins PJ, Moran M. Predicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patients. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 26:209-213, 2011.

5. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Kraus VB, Lohmander LS, Abbott JH, Bhandari M, Blanco FJ, Espinosa R, Haugen IK, Lin J, Mandl LA, Moilanen E, Nakamura N, Snyder-Mackler L, Trojian T, Underwood M, McAlindon TE. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 27:1578-1589, 2019.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.