Good hygiene, best practice

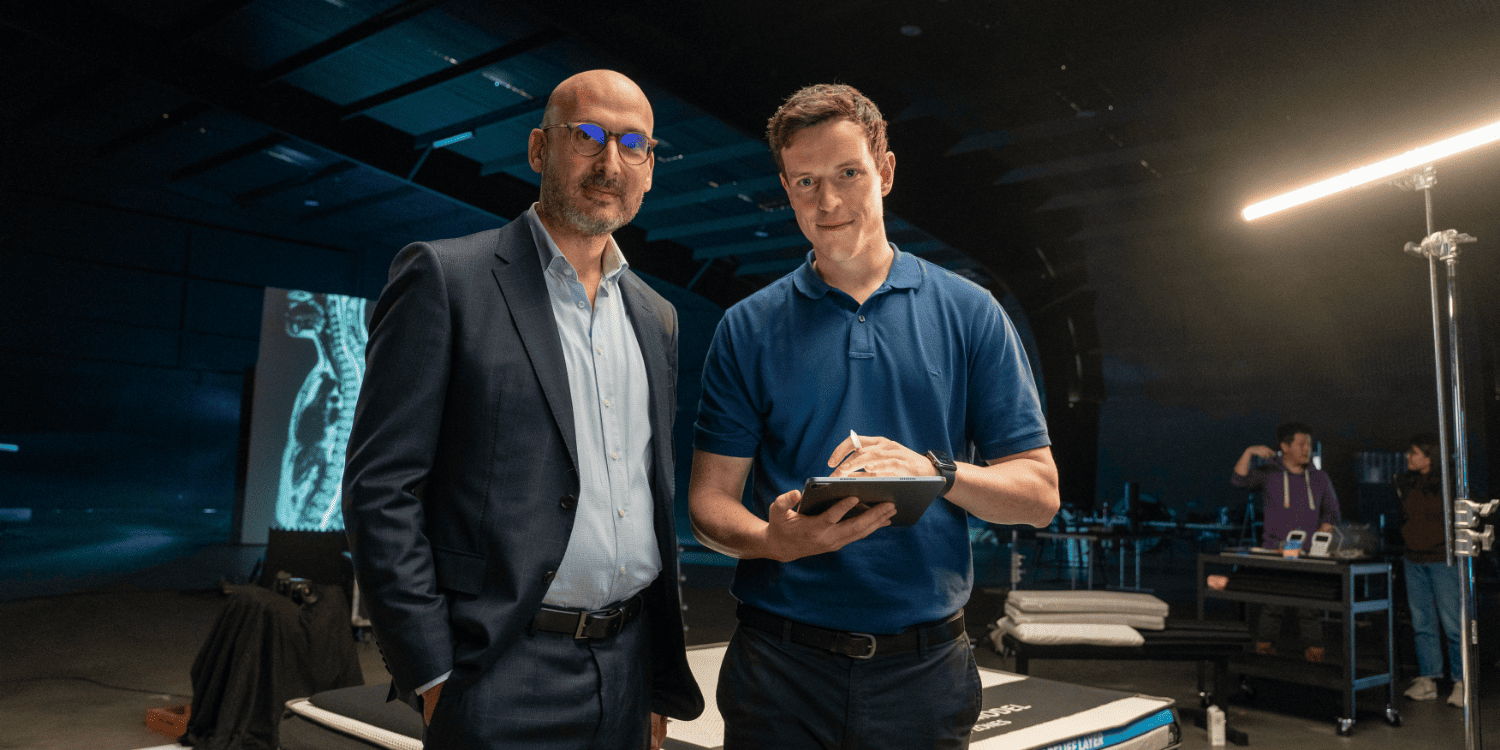

Good hygiene practice is a crucial part of a physiotherapist’s duty of care and has never been so important, particularly given heightened hygiene awareness among consumers. Ibrahim Samaan, practising physiotherapist and founder of hygiene company Purifas, outlines his hygiene practice guidelines for private physiotherapists.

What are the go-to hygiene regulations therapists should follow in order to minimise the risk of infection in their clinics and therapy environments? The astonishing answer is that there are none.

To date, physiotherapists have been left to their own devices— to attend therapy forums, to navigate their way around numerous websites, to approach government bodies, to scour the media and to ask their colleagues and professional networks—in an attempt to determine the areas of risk and how to manage them effectively in a clinical setting.

It was this distinct lack of any clear and direct instruction that prompted me to develop a set of best practice guidelines (based on current research and evidence) specifically for therapy professionals.

These essential guidelines are laid out below in five easy-to-follow steps.

Clients with symptoms of illness should be strongly advised not to attend therapy

It is well established (Sartwell 1966, Brookmeyer 2015, Backer et al 2020) by virologists and medical experts that the infectious period after contraction of an infectious pathogen begins before the carrier becomes symptomatic (if at all).

While the overlap may vary between diseases, the incubation period is usually 7–10 days and a carrier typically becomes infectious within the latter five days.

While it is near impossible to monitor infection without symptoms, it should be made explicitly clear that a client with any symptoms, no matter how mild, should not attend therapy as they have the potential to be a carrier of an infectious pathogen.

Extra caution may also be established by asking clients who have been exposed to people who are ill to also reconsider their attendance.

You can communicate this to your clients by:

• displaying signs in high-traffic areas of your clinic

• including a hygiene requirement section on your website

• promoting your policies on social media

• explicitly asking your clients at the time of booking or when confirming their appointment.

Clients and therapists should wash their hands before and after therapy

The primary focus of hygiene research has been on hand hygiene and its effectiveness in diminishing the transmission of disease via contact (Johnson et al 2005, CDC 2002).

Handwashing is accepted as essential, especially in healthcare. However, the issue is compliance by healthcare personnel and attendants. Studies show the compliance rate to be as low as 10 per cent (Grayson et al 2011, Azim & McLaws 2014).

Therapy professionals must observe frequent and stringent handwashing at three critical points:

• upon entry to the clinic

• prior to treatment

• immediately following contact with a client.

Clients should be given access to facilities to wash their hands upon entry to the clinic and at the completion of their treatment.

While thoroughly washing their hands, they must also limit the use of re-usable towels, which have been shown to harbour bacteria despite repeated washing (Sifuentes et al 2013).

Healthcare-associated infections are a substantial contributor to the healthcare burden and preventable disease figures.

More than 12 per cent of MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) infections are contracted in a community setting, so it is imperative that the increased hygiene practices implemented to mitigate the COVID-19 viral pandemic remain in place and become the new norm.

Within the therapy room, only apply single-use, fit-for-purpose hygiene products to all shared surfaces and items.

Single-use protective materials are known to be more hygienic, preventing the spread of potential infectious pathogens

The main points of entry and exit of a pathogen are through the nasal mucosal openings (Alberts et al 2002).

Prone therapies use a shared face hole, which can significantly increase a client’s risk of cross transmission via contact, droplets and potentially airborne microbes shed from the nose, mouth and even eyes.

Single-use materials dramatically reduce the risk of cross contamination by bacteria, flora or microbes.

Research (Sifuentes et al 2013) has shown that re-usable materials—such as towels, pillowcases and bed linen—can harbour bacteria despite hospital-grade washing.

In particular, it was shown that Staphylococcus aureus can survive up to three weeks in cotton towels, which are commonly used in therapy clinics and hospitals, despite regular laundering (Sifuentes et al 2013).

It was concluded that normal washing or laundering of towels, whether done in-house or externally, was not enough to remove all viable microorganisms (Sifuentes et al 2013).

Sanitise all shared surfaces after each therapy session

All shared surfaces should be sanitised between each client to minimise the risk of cross transmission.

To effectively sanitise a surface, research indicates that it must first be cleaned with a detergent and then disinfected with an appropriate Therapeutic Goods Administration-approved antibacterial or sanitising agent (CDC n.d., Hota 2004) (Remember to ensure that these agents are safe for use in a clinical setting).

All high-traffic areas and contact points should be cleaned regularly

High-traffic contact points, such as door handles, armchairs, waiting room areas and reception desks, are cross-transmission risks, especially in facilities with a high turnover of clients.

All areas that customers come into contact with upon entry to and exit from the clinic, such as bathroom areas, should be cleaned and sanitised regularly.

There is evidence to show a significant reduction in healthcare-associated infections when an employee is hired specifically to clean and sanitise high-traffic and common areas (Doll et al 2018).

Depending on the size of your clinic, this may not be feasible. In that case, these hygiene and safety tasks should be clearly assigned to the appropriate personnel, including clear outlines of what needs to be done and how often.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has provided some resources to assist business owners and health-related professionals to develop an environmental cleaning program.

Making these five steps standard practice in your clinic or therapy setting will help maintain a safe and hygienic environment for your clients and contribute to a reduction in community transmission of illness.

Purifas FaceShield and Best Practice Guidelines are APA endorsed—click here for more.

>> Ahpra-registered physiotherapist Ibrahim Samaan is the founder of Purifas, a healthcare company committed to reducing the risk of infection and improving comfort during therapy treatments. Ibrahim is the winner of two Gold 2021 Asia-Pacific Stevie Awards and is a 2020–2021 Physiotherapist of the Year Finalist in the Allied Health Awards for his efforts to improve hygiene standards in the physiotherapy sector.

- References

-

GUIDELINES 1. SARTWELL, P “The incubation period and the dynamics of infectious disease”, American Journal of Epidemiology (1966) – Accessed online; 04/05/2020 http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/pubhealth/p8462/misc/sartwell.pdf

• (1a) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118445112.stat05241.pub2 Brookmeyer, Ron. Incubation Period of Infectious Diseases. Wiley Online (2015). Accessed 04 May 2020 at https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat05241.pub2.

• (1b) Backer Jantien A, Klinkenberg Don , Wallinga Jacco . Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20–28 January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5):pii=2000062. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062

2. Johnson, PDR, Martin, R, Burrell, LJ, et al. Efficacy of an alcohol/chlorhexidine hand hygiene program in a hospital with high rates of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. Medical Journal of Australia (2005) 183:10 509–515

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR 2002;51(No. RR16). Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5116.pdf. Accessed 5 May, 2020

4. Grayson, ML, Russo, PL, Cruickshank M, et al. Outcomes from the first 2 years of Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Medical Journal of Australia, 2011; 195(10): 615–620.

5. Azim, S, McLaws, ML (2014) Doctor, do you have a moment? Medical Journal of Australia 2014; 200(9)

6. Sifuentes, LY, Gerba, CP, Weart, I, Engelbrecht, K, Koenig, DW. Microbial contamination of hospital reusable cleaning towels. American Journal of Infection Control. 2013 Oct;41(10):912–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.015. Epub 2013 Mar 22.

7. Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. Cell Biology of Infection.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26833/

8. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention - “Cleaning and Disinfecting your Home” Accessed 04 May 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/disinfecting-your-home.html

9. Hota B, Contamination, Disinfection and Cross-Colonizations: Are hospital surfaces reservoirs for nosocomial infection? Clinical Infectious Diseases 2004; 39:1182–9

10. Doll, M, Stevens, M, Bearman, G. Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection of Patient Areas; International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2018; 67: 52–57 -

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.