Improving pain for young people

Improving the quality of life for young people experiencing persistent pain is a focus of interest for APA member Bec Fechner.

In her role as a senior physiotherapist with the Queensland Interdisciplinary Paediatric Persistent Pain Service (QIPPPS) at Queensland Children’s Hospital, Bec Fechner supports children and their families to understand the biopsychosocial complexity of persistent pain.

She has been with the service since it opened three years ago, bringing years of experience gained in child development, musculoskeletal physiotherapy and adult persistent pain throughout Australia and the UK. She has worked as an educator for the Pilates Institute of Queensland, helping physiotherapists and exercise physiologists explore body–mind exercise and ‘apply complex motor control clinical reasoning to their practice through a biopsychosocial lens’.

‘I had moved into a niche area of persistent pain in my career and when I heard the service was starting, I was really excited,’ she says. ‘I had a bias towards rehabilitation for people experiencing persistent pain, and was interested in working more with young people.’

The interdisciplinary pain service offers a ‘gold standard’ in paediatric care, with allied health and medical staff researching and consulting with peers at children’s hospitals across Australia, the US and UK to benchmark standards of care before launch. Bec is also a panellist on the Queensland Children’s Hospital Paediatric Persistent Pain ECHO series that brings together tertiary and local healthcare providers across the state in facilitating collaborative, evidence-based and best practice care for paediatric persistent pain. ‘There were lots of literature reviews, emails and teleconferencing when getting things started,’ she says of the collaborative approach.

Access to the evidence-based persistent pain service is by doctor referral and it is available to children up to the age of 18 who live in Queensland. Those living remote to the hospital are linked through local services and access the pain services team through telehealth. The service was initially funded as a trial in its first 18 months of operation, becoming permanent in late 2017.

‘Some enthusiastic hospital staff rallied together for families and patients as they could see the hospital was struggling to support children with such complex presentations without a dedicated service.’ Bec says. ‘The trial was successful and now it is a permanent part of the Queensland Children’s Hospital.’

The response from hospital staff, health professionals and families within the wider community has been encouraging. ‘It’s a positive service offering; we are still small and seeing only the tip of the iceberg of children with persistent pain, but the word is spreading that we are here as a supportive service. It is alleviating the pressure that was previously put on hospital staff in the acute setting to find answers and deliver treatment options.

‘For me, I’ve achieved some nice collaborations with other physios throughout Queensland during those three years. I never thought that this job would also include collaborating with physios all over the world. It’s an exciting time to be working in the field of persistent pain, as its study has come a long way in the past 10 years.’

She says the recent release of a proposed new definition for pain from the International Association for the Study of Pain taskforce reflects how clinicians and researchers are thinking about how it is managed and understood. ‘The proposed definition states that it [pain] is an aversive sensory and emotional experience typically caused by, or resembling that caused by, actual or potential tissue injury. So, understanding that pain can exist in the absence of injury forms the crux of our intervention. If we put this in a different way, pain is an output for the brain, serving a purpose for the child to communicate threat and/or distress. Threats can be hard to find, as they are not always organic, such as a broken leg.’

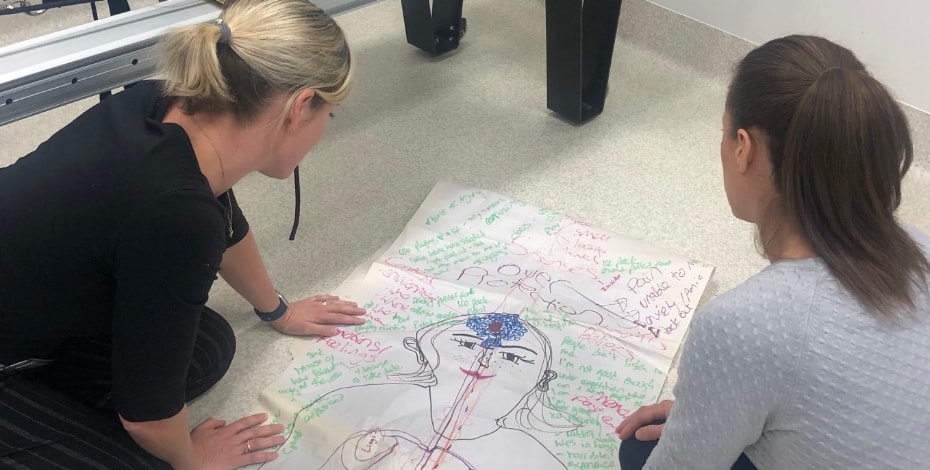

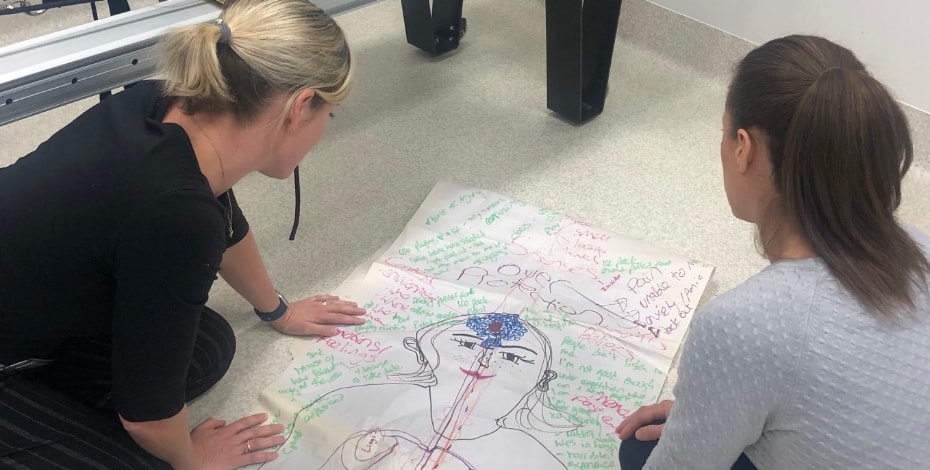

Persistent pain presentations seen at QIPPS include headaches, widespread joint, back, abdominal, neuropathic and complex regional pain syndrome. Patient assessment and intervention aligns to the shift in how pain has been categorised, with a biopsychosocial interdisciplinary approach involving a team that includes a pain specialist, nurse practitioner, psychiatrist, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and a music therapist. Together they address the psychological, social, occupational and biomedical factors related to each child’s persistent pain, which includes their functional ability to participate in school and physical activity, their sleeping patterns, relationships with family and other people, and mental health history. The team works to engage the child through activities, such as play, art, music, drama, dance, sport and cooking.

‘From a physiotherapy perspective, as we play together during these activities, we try and assess a child’s concept of pain. That is, how they understand what pain is. We use pain science to create a common language for pain and work together with families to hunt for “threats” or “dangers” that are triggering a pain response. When they learn what is happening in their nervous system through pain science, they can better understand their body’s own symptoms such as fatigue, nausea and pain.

‘Children begin to feel safe to explore their thoughts and feelings and connect with other therapies, such as psychology. Through this biopsychosocial approach, kids can start to feel confident to engage in school and sport again and reconnect with life, which is our mission,’ says Bec, laughingly adding that not all patients are initially receptive to treatment. ‘Our patients are in a really tough position—they usually hate us at first and then learn to love us.’

On board the pain revolution, she is passionate about changing the way clinicians understand pain, and is excited to see where research about persistent pain, particularly for children and young people, is heading. In her day-to-day assessment, children have withdrawn from sport, exercise and school due to developmental challenges, pain, injury, illness, poorly understood body symptoms such as hypermobility or sensory sensitivity, and anxiety and depression.

‘These young people experience deconditioning, and require a lot of support to rehabilitate. This has inspired me to pursue understanding the developmental impacts of persistent pain, that is, what happens when a child withdraws from play and physical activity for months or years at a time due to pain.’

She has implemented the use of a norm- referenced developmental assessment tool into the QIPPPS model of care to enable opportunities for rich, quality research into the associations between developmental delay and persistent pain in children and young people.

‘Who we see are generally kids who are really struggling in life and unable to function—in not getting to school, and not being able to participate in any activities. We are seeing kids totally disengaged from life—we try and help families understand how this is impacting their developmental trajectories, and support them to re-engage,’ she says. ‘It is fulfilling work.’

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.