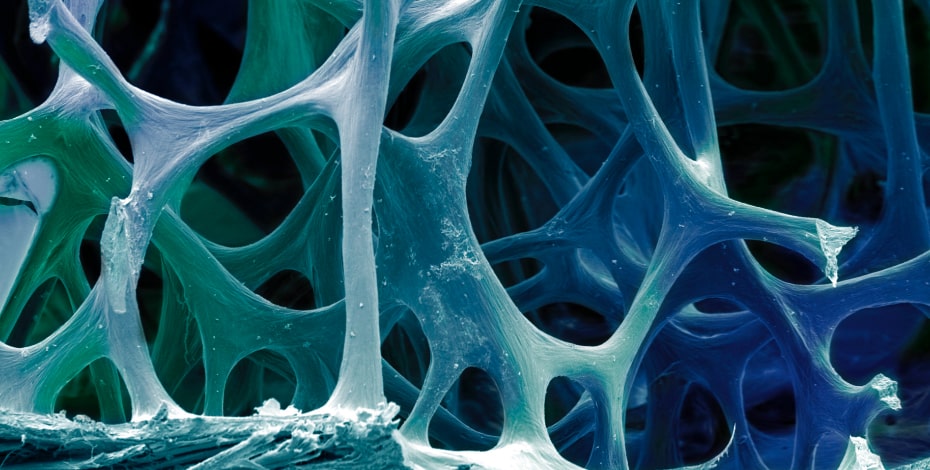

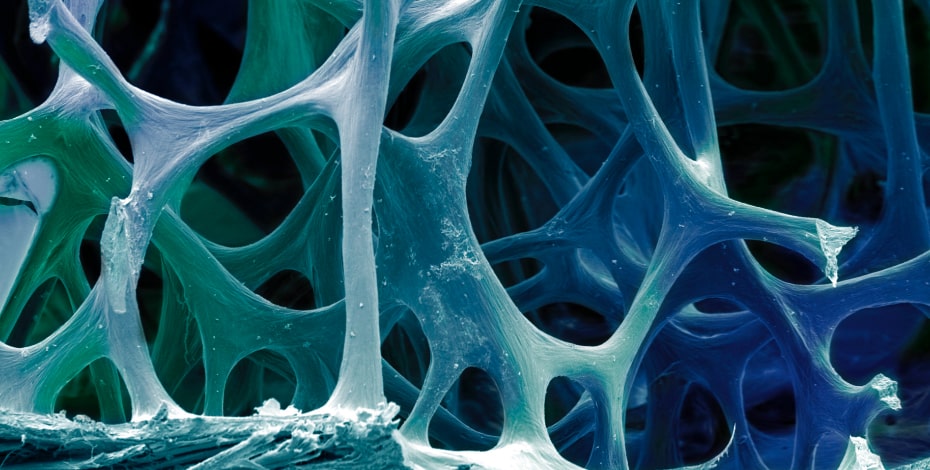

Physiotherapy and bone health

Five discussion points about exercise for bone health across the lifespan are explored by Brea Kunstler, Shae Martello, Christie Wall, Genevieve Dwyer and Rebecca Fagan.

1. Strong bones start in childhood

One in two women and one in four men will suffer an osteoporotic fracture after the age of 50 but while the problem manifests in adulthood, its origin is in childhood.

Behaviour patterns set in childhood are therefore critical to bone health in later life.

Weight-bearing activities, developing strong muscles and being physically active in infancy and childhood optimises bone accrual and maximises peak bone mineral density, which in turn is pivotal to ensuring good bone health across the lifespan.

There are many different options beneficial for bone health and suggesting activities in a child’s local area can improve engagement and enhance participation.

For example, a child may have tried playing tennis but not enjoyed it. However, they may then try a team sport such as soccer and find this more enjoyable, with greater peer interaction. If they enjoy an activity, they are more likely to continue to participate in it into adulthood.

Encouraging families to exercise together can also create positive behaviours, as children will often look up to their parents or older siblings as role models. It can be as simple as going out to the park to kick a ball around as a family.

2. Resistance exercise is safe and necessary in adolescence

Increasing bone mineral density during adolescence is equally as important for preventing osteoporosis in later life.

While we know the benefits, it is sometimes tricky to convince younger people to make changes to their activities now to benefit them in the long term.

Physiotherapists are sufficiently skilled to instruct clients on how to perform resistance training for healthy bones.

However, sometimes teenagers and their parents can be concerned about young people hurting themselves when participating in resistance training.

Physiotherapists must teach both teenagers and their parents about correct technique, safe loading and progression when performing resistance training.

This helps teenagers and their parents to know how to exercise safely, calming nerves and potentially preventing avoidance of this important exercise type.

Learning safe and correct technique supports the development of correct movement patterns, setting teenagers up to safely participate in resistance training throughout their life.

One way to support teenagers to participate in resistance training is by running weekly circuit-style classes that conclude with a discussion on topics including nutrition, mental health, posture, sleep, stretching and ways to incorporate exercise into their life.

During the class, it is important to supervise the teenagers and correct their technique if necessary, ensuring they develop the skills and coordination they need to progress to an independent resistance program.

3. Young people with disabilities can have a high risk of developing osteoporosis

Young adults (aged between 18 and 40 years) with paediatric-onset disabilities (eg, congenital musculoskeletal, neurodevelopmental and chromosomal abnormalities and chronic respiratory conditions) are at significantly higher risk of poor bone health and increased risk of fragility fractures compared to those without disability.

Strategies to optimise bone strength should commence early in life and physiotherapists are well positioned to foster behaviours to achieve this outcome.

Secondary osteoporosis related to immobility experienced by people with conditions such as cerebral palsy or Duchenne muscular dystrophy can lead to significant morbidity, pain and low-trauma fractures throughout their life.

Simple everyday activities such as transfers and continence care can be painful and stressful experiences.

Implementing a program to facilitate loading, such as the use of a standing frame for those unable to stand independently, can assist to maintain and even improve muscle and bone health, leading to a better quality of life.

4. Bones love exercise but only when it is partnered with sufficient energy intake

Many adults exercise to maintain or improve their health.

These ‘recreational athletes’ might exercise every day, or close to, and not realise that they might be doing as much exercise as some competitive athletes.

Competitive athletes often have support teams who ensure that they are eating enough to fuel their activity, but recreational athletes don’t.

Recreational athletes often exercise a lot with the goal of losing weight, restricting their fuel intake and depriving themselves of the fuel needed to exercise, recover effectively and perform daily activities.

Exercising a lot and not fuelling enough is a recipe for poor bone health.

Bones need fuel to become stronger in response to the exercise performed. Inadequate fuel intake and high exercise levels can lead to low energy availability, where the person doesn’t have enough energy to perform normal bodily functions (eg, healthy reproductive function for men and women) as well as to support the demands of daily exercise.

The longer low energy availability lasts, the weaker our bones get as they simply don’t have the energy available to maintain their strength.

This can lead to lower limb stress fractures, extensive rehabilitation periods and mental health concerns associated with injury and time away from sport.

Physiotherapists often have clients seeking advice about how to improve their running.

The client may report that they have been increasing their distance and session frequency or doing some speed training and not seeing any improvements.

In fact, some report that they are getting slower, experiencing poor mood and frequent injuries (eg, shin splints, stress fractures).

These people have often increased the amount of exercise they do to try to improve their performance, but they haven’t increased their energy intake and are seeing the results of low energy availability.

This is where physiotherapists must discuss the client’s general health rather than just focusing on running performance.

5. Yoga can improve bone health in older adults

Osteoporosis is not an inevitable part of ageing. Evidence shows that exercise such as yoga can protect bones, reverse osteoporotic bone loss and improve strength and balance.

Yoga has become increasingly popular with people of all ages (14–50+). More Australians now do yoga than play soccer, cricket, tennis or golf, or do Pilates or aerobics (Roy Morgan, 2018).

Many physiotherapists play a role in prescribing and delivering yoga programs, including making modifications to suit the individual’s therapeutic needs.

There are now so many styles of yoga and class supervision levels, from energetic power flow to restorative, chair-assisted, yin yoga and yoga nidra relaxation.

It is important that physiotherapists know what is offered before referring clients to a general community class.

Yoga practices can easily be prescribed as part of a treatment plan. Yoga is not just about flexibility and twisting into a pretzel. The heart of yoga is teaching mindful movement with body and breath awareness.

Flexibility, strength, bone health and balance develop over time with continued practice. Yoga is a great fit for physiotherapists working with a modern biopsychosocial approach.

Basic yoga training can be integrated into many areas of practice, such as children with autism, teenagers, cancer recovery, multiple sclerosis, prenatal and postnatal care, back care, falls and balance, persisting pain and older adults.

It also increases feelings of wellbeing, which enhances exercise compliance.

Click here for an infographic poster version of this article. Click here to access the Australian Government physical activity guidelines and here for the UK’s magic pill benefits of exercise.

>>Dr Brea Kunstler, APAM, is a behaviour change scientist at BehaviourWorks Australia and provides online coaching services as a physiotherapist. She has a PhD in physical activity behaviour change and uses her passion for physical activity in her role as co-convenor of the APA advisory group Physiotherapists for Physical Activity.

>>Shae Martello, APAM, works in private practice at Healthfocus Physiotherapy in Albury-Wodonga and has special interests in resistance training, nutrition and adolescent health. She is currently completing the Master of Clinical Rehabilitation through the University of Melbourne.

>>Christie Wall works as the Bone and Mineral Coordinator at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead. A senior paediatric physiotherapist with specialised skills in the area of bone health, Christie provides a statewide clinical service for children with bone and mineral disorders.

>>Dr Genevieve Dwyer, APA Paediatric Physiotherapist and HNEKids Rehab Team clinician (Newcastle), is a senior paediatric physiotherapy lecturer at Western Sydney University. Her paediatric research interests include physical activity for all children, outcomes for preterm infants, telehealth experiences during COVID and development of the Mini-Wobbly shoe to train balance.

>>Rebecca Fagan, APAM, is a clinical physiotherapist, a yoga teacher and educator in therapeutic yoga. She established her Physioyoga & Wellbeing practice in 2013. Rebecca brings her passion for yoga into education and runs online therapeutic yoga training courses: Restorative Yoga Nidra Method and Mindfulness, and Yoga for Common Musculoskeletal Conditions.

- References

Fact 1 References:

Bland VL et al (2020) Association of objectively measured physical activity and bone health in children and adolescents: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Osteoporosis International 31:1865–1894.

Santos L, Elliott-Sale KJ and Sale C (2017) Exercise and bone health across the lifespan. Biogerontology 18:931-946.

Troy et al (2018) Exercise early and exercise often: effects of physical activity and exercise on women’s bone health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 878-895.

Fact 2 References:

https://eprints.qut.edu.au/77058/

https://www.strengthandconditioning.org/news/692-child-and-youth-resista...

Fact 3 References:

Whitney DG et al (2020) Early-onset noncommunicable disease and multimorbidity among adults with pediatric-onset disabilities. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 95(2):274-282.

Jefferson J et al (2016) Clinical guidelines for management of bone health in Rett Syndrome based on expert consensus and available evidence. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0146824.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146824

Fact 4 References:

https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/48/7/491.full.pdf?with-ds=yes

https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2019/04/22/relative-energy-deficiency-in-spor...

https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/1/38

Learn more about REDS and female athlete health https://www.ais.gov.au/fphi

Fact 5 References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4851231/

https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7544-yoga-pilates-participation-decem...

Lu YH, Rosner B, Chang G, Fishman LM. Twelve-Minute Daily Yoga Regimen Reverses Osteoporotic Bone Loss. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2016 Apr;32(2):81-87.

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.