The science of behavioural change

Physiotherapy is much more effective when patients are able to change their behaviour and adhere to treatment, yet there are a number of barriers to behavioural change. Dr Tamina Levy explores a systematic approach designed to bring about the differences that will help patients the most.

Human behaviour, or ‘anything a person does in response to internal or external events’, is a fundamental component of physiotherapy practice.

Facilitating behaviour change is the key to most areas of physiotherapy work, from clinical work to policy change and guideline implementation.

There are three main ways we aim to influence behaviour—initiating a new behaviour, stopping an existing behaviour or changing how a behaviour is performed.

To change behaviour, we need to understand it.

The evidence tells us that in order to bring about change that is sustained in the long term, we should integrate sound theoretical models into our planning, implementation and evaluation of behaviour change programs or interventions.

Despite this evidence, many physiotherapists report a lack of knowledge about behaviour change and a lack of confidence in choosing the ideal model for their specific scenario.

In my PhD, ‘An exploration of adherence to intensive exercise in stroke survivors’, I explored a wide range of behaviour change models and considered the evidence supporting them as well as the ease of application.

The model I adopted throughout my studies was the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Michie et al 2011).

I found the BCW to be logical and simple to apply, while providing clear processes and producing a rich analysis.

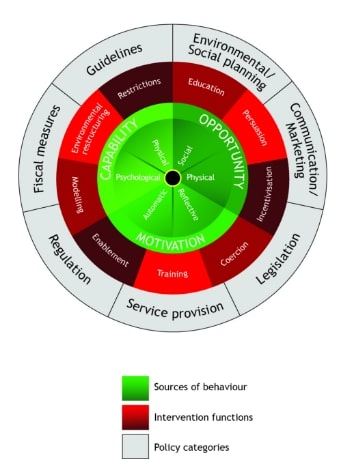

The Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al 2011).

The BCW was developed from a synthesis of 19 behaviour change frameworks and expert consensus and is widely used in the implementation science literature.

It provides a structured, systematic method for understanding behaviour, planning a behaviour change intervention and considering how it will occur.

The BCW consists of three layers and we work logically from the centre of the wheel outwards.

The hub of the wheel, the COM-B model, identifies the sources of behaviour that could be the target for intervention.

Surrounding this is a layer of nine behaviour change ‘functions’ that we can select to bring about change, based on our COM-B analysis.

The outer layer identifies seven policy options, which are important to consider when planning large-scale intervention projects.

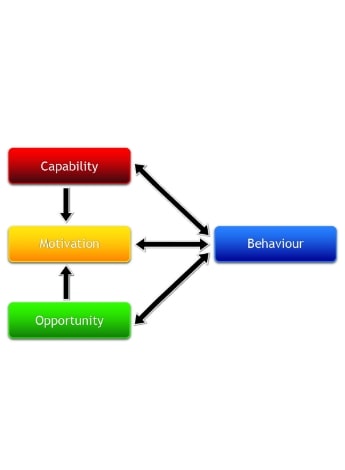

To produce different behaviour, something must change within at least one of the three main behavioural categories in the COM-B model (capability, opportunity or motivation).

Capability can be classified as either physical (having the physical skills, strength or stamina to perform the behaviour) or psychological (having the necessary mental processes or psychological skills).

Psychological capability encompasses important phenomena including memory, attention, decision-making, interpersonal skills and self-regulation.

Opportunity can be physical (what the environment allows in terms of time, resources or physical barriers) or social (interpersonal influences, social cues and cultural norms).

Motivation can be considered reflective (involving self-conscious evaluations, plans and belief systems) or automatic (wants, needs, impulses and habits).

An analysis based on these six components will help us identify what needs to change in the person or the environment in order to achieve a change in the target behaviour.

As well as using this model in our professional roles, we can apply it to our own behaviour.

For example, I recently decided I should try to get to the gym a bit more.

I know I am capable, because I already go twice each week, and I do have opportunity, as I can set the alarm to go before work.

My main barrier is motivation—it’s hard to set the alarm at 5.40 am in the middle of winter when it’s cold.

If I want to change this target behaviour, I need to develop a plan focused on the motivation aspect of my behaviour.

Motivation is central to the COM-B components and it is often the focus—if we have capability and opportunity, we will do what we are most motivated to do at that time.

The PRIME (Plans, Responses, Impulses/Inhibitions, Motives, Evaluations) model of motivation (West & Michie 2020) aligns with COM-B and can be integrated into your BCW analysis and intervention planning if motivation is considered the central factor.

The BCW can be used to design interventions, to identify what is in a current intervention and as a framework for evaluating interventions.

The COM-B model can be applied at any level, from an individual to groups and larger populations.

For many of us working in a clinical environment, it is a practical tool that ensures that we consider all the potential barriers and enablers to behaviour change.

At an individual level, if you are working with a patient and you consider a home-based exercise program to be an important part of their management, the model can be used to guide you in developing a program that is tailored and therefore more likely to be adhered to.

This is because you can work systematically through the aspects of capability, opportunity and motivation and discuss any barriers that the individual patient may experience.

For example, let’s say you have a patient, Jim, presenting with low levels of physical activity following a period of hospitalisation.

You can ask, ‘What would it take for you to do 30 minutes of exercise every day?’ and consider prompts specific to capability such as ‘I would need to know more about it’, ‘I would need better skills’ or ‘I would need more mental strength’.

Prompts specific to opportunity could include ‘I would need to have more time’ or ‘I would need more support from others’ and motivation prompts could include ‘I would need to believe it is worthwhile’, ‘I would need to develop a habit’ or ‘I would need to feel like I want to do it’.

An in-depth analysis following this COM-B structure will then give you a list of modifiable barriers that you can address as you plan your exercise program.

The COM-B system—a framework for understanding behaviour (Michie et al 2011).

For those of us wanting to develop interventions with a wider implementation, the BCW can also provide a comprehensive and systematic process to follow.

In addition to COM-B, Susan Michie and colleagues developed the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Atkins et al 2017).

This tool predates COM-B and provides a more granular, detailed analysis of behaviour.

It has 14 domains: knowledge; skills; memory, attention and decision processes; behavioural regulation; social/professional role and identity; beliefs about capabilities; optimism; beliefs about consequences; intentions; goals; reinforcement; emotion; environmental context and resources; and social influences.

The TDF has been used extensively to improve implementation of evidence-based practice in a variety of health settings.

The COM-B components link to the TDF domains and the two can be used individually or together.

One possibility would be to use COM-B first to ‘screen’ the patient’s behaviour and provide an indication of which areas may need a more in-depth analysis with the TDF domains.

There are many examples in the literature of large studies that have used COM-B and TDF in their intervention design and implementation, such as the development of an intervention to support adherence to home-based exercises in people with knee osteoarthritis (Nelligan et al 2019) and an intervention to reduce ‘sitting time’ in desk-based workers (Ojo et al 2019).

Once the ‘behavioural diagnosis’ (COM-B) has been completed, the BCW directs us to the next step as we move out from the centre of the wheel: selecting intervention functions.

The nine intervention functions are: education (increasing knowledge or understanding), persuasion (using communication to induce positive or negative feelings), incentivisation (creating an expectation of reward), coercion (creating an expectation of cost), training (imparting skills), restrictions (using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the behaviour), environmental restructuring (changing the physical or social context), modelling (providing an example for people to aspire to) and enablement (increasing means beyond education/training or environmental restructuring).

Each of the six COM-B components aligns to one or more intervention function and within the BCW guide (Michie

et al 2014) there are easy-to-use ‘grids’ to assist with this process.

For example, when you talk to your patient Jim, you discover that one barrier he is facing is that he does not really understand (psychological capability) why he needs to do 30 minutes of exercise each day or believe that it will help him (reflective motivation).

A behaviour change function that could be considered to target psychological capability would be education—you could spend time with Jim, looking at information on healthy living and providing him with resources to improve his knowledge.

To address reflective motivation, one approach would be to provide examples of positive case studies where people have experienced improved quality of life by increasing physical activity (persuasion/modelling).

For ‘large-scale’ behaviour change interventions, the next step is to consider what policies would support the delivery of any intervention functions identified.

Seven policies have been included that aim to help support interventions: communication/marketing, guidelines, fiscal measures, regulation, legislation, environmental/social planning and service provision.

The BCW guide (Michie et al 2014) provides recommendations for which policy categories are likely to be appropriate and effective in supporting each intervention function.

The final stages of the BCW process are to select specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and consider how they will be delivered.

A BCT is the active component of the intervention and BCTs have been synthesised into a taxonomy (Abraham & Michie 2008) of 93 techniques across 16 categories.

Again, the BCW guide provides details about the definitions of the BCTs and links to the intervention functions.

Examples of BCTs that could be useful when working with Jim include goal setting and self-monitoring of behaviour.

The science underlying behaviour change is complex and most intervention strategies require prioritisation and judgement on the basis of the available evidence.

Of course, the amount of time and resources we put into developing interventions will vary depending on the scale of the target behaviour.

Developing an intervention to improve the rate of hand hygiene in a hospital ward will require a more detailed analysis and plan than getting one patient to do an exercise program.

However, using a process such as the BCW and COM-B model will ensure that we systematically consider all factors specific to the target behaviour, at any level.

While we may be successful at changing behaviour, the biggest challenge remains maintaining change over time.

Tamina Levy's research includes exercise programs for chronic neurological conditions, with a focus on behaviour change.

Many of our patients (and ourselves) will make a great start with exercise programs and other forms of behaviour change, but struggle to maintain these changes.

Three key factors have been identified as critical for maintenance of behaviour change.

Firstly, there needs to be a sense of satisfaction with the change that has been made—does the experience match the expectation of behaviour change?

For physiotherapists, the key here is managing expectations.

Secondly, maintenance of change seems to be driven by intrinsic motivation or an inherent interest in the behaviour.

This can be fostered by concepts such as feeling competent with and connected to the behaviour, so it’s important to help the patient to carefully select behaviours that have meaning for them.

Finally, the most important factor affecting maintenance of behaviour change is habit formation.

This is the ultimate in behaviour change—habits will sustain change even when motivation reduces.

How can we move behaviour change to this level of habitual behaviour?

Well, that’s a whole science of its own.

We should consider that habits rely on learned associations and situational cues so repeated actions within a specific context may assist.

Within a clinical setting, we should consider individual patients’ potential barriers in terms of capability, opportunity and motivation.

This will enable us to tailor programs that address modifiable barriers and will lead to improved adherence.

From a personal perspective, when we consider issues such as our own physical and mental health, work-life balance and relationships, we should again explore our behaviour from a COM-B viewpoint and identify target behaviours that could be addressed to improve our own quality of life.

Now I need to go and set my alarm and get my gym bag ready!

>> Dr Tamina Levy APAM is a clinician researcher with over 30 years’ clinical experience in neurological rehabilitation. She is an advanced practitioner in neurological rehabilitation at Flinders Medical Centre and a lecturer at the College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University. Her ongoing research interests include implementation of exercise programs for chronic neurological conditions (including stroke), focusing on behaviour change.

- References

-

West, R. & Michie, S. (2020). ‘A brief introduction to the COM-B Model of behaviour and the PRIME Theory of motivation.’ Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/WW04E6.2.

Abraham, C. & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379-387.

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., Foy, R., Duncan, E. M., Colquhoun, H. & Grimshaw, J. (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Journal of Implementation Science, 12(1): 77.

Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Silverback publishing.

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Journal of Implementation Science, 6(1): 42.

Nelligan, R. K., Hinman, R. S., Atkins, L. & Bennell, K. L. (2019). A Short Message Service Intervention to Support Adherence to Home-Based Strengthening Exercise for People With Knee Osteoarthritis: Intervention Design Applying the Behavior Change Wheel. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(10): e14619.

Ojo, S., Bailey, D., Brierley, M., Hewson, D. & Chater. (2019) Breaking barriers: using the behaviour change wheel to develop tailored interventions to overcome workplace inhibitors to breaking up sitting time. BMC Public Health, 19:1126.

-

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.