The search to find your true self

PROFILE An Ancient Greek aphorism, from the Delphic maxims, is ‘know thyself’. For APA Sports and Exercise Physiotherapist Peter Dornan, the journey to know his own self has been a challenging but ultimately triumphant one. Melissa Mitchell speaks to the man about his search for a meaningful life and how it can help others.

With one outstretched arm extending skyward, the bronze statue of Mt Everest climber Sharon Cohrs (below) captures a poignant moment of her reaching for the support of her husband, Allan. Forever frozen in that moment, Sharon’s ascent of the mountain is extraordinary when put into context. At age 36 Sharon was diagnosed with breast cancer and, after undergoing aggressive treatment, she started walking on a treadmill. The couple then devised a heavy and challenging exercise program. Three years after her diagnosis, at age 39, Sharon stood on the summit at Mt Everest, becoming the first breast cancer survivor to do so—a feat which truly inspired the statue’s creator, physiotherapist Peter Dornan.

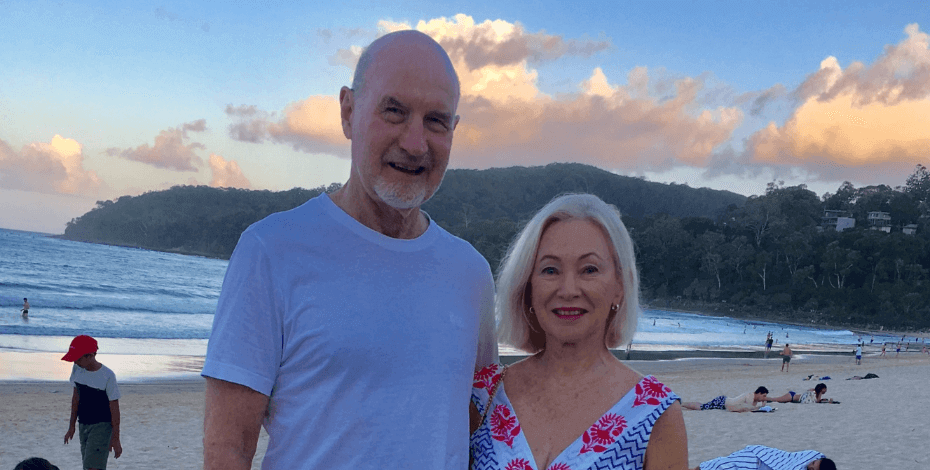

It is easy to draw parallels between the lives of Sharon and Peter. Both survived intense and invasive cancer treatment: Peter was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1996 at age 52. Both had the loving support of their partners: Peter’s wife Dimity has been an anchor and an inspiration since the couple wed in 1967. And both Sharon and Peter showed incredible inner strength in the face of extreme adversity.

How Peter coped with his own cancer diagnosis and the impact it has had on his life and that of countless other men with prostate cancer is in itself an incredible story. But for Peter, what it mostly comes down to is this—once you know yourself you can be a much stronger person. The author of eight books has found meaning in many forms on his journey—a journey that really began when he walked the Kokoda Trail at age 40.

Peter’s father had fought on the trail but never discussed his war experiences with his son. When his father died at an early age from injuries he’d received on the Kokoda Trail, a young Peter was left with many unanswered questions. Walking the trail was an adventure and offered insights into Australia’s military history, his father’s likely experiences and some insights into his own identity.

‘At the end of the Kokoda Trail walk, I was profoundly changed. Even though I was very fit and I got lost many times because there was no map … within two hours I knew a little bit about what it meant to search inside yourself,’ Peter says. ‘I responded to that little voice inside saying “you have to do this, you haven’t done this yet but you can”. Bit by bit you scrape away at the veneer and find out what is underneath. The trappings fall off and you find out who you are. That’s been an important part of my journey, to try and find out what I was capable of achieving.’

A little over a decade later, Peter’s mettle was tested when he was confronted with the biggest challenge of all—his prostate cancer diagnosis and the resultant life-saving prostatectomy. At a time when very little information about prostate cancer surgery side-effects was available to patients—and even less support—Peter was left battling incontinence, erectile dysfunction and psychosocial legacies that had a huge impact on his life, marriage and his career.

‘I got myself absolutely depressed, the side-effects were absolutely horrendous. It was a situation I hadn’t had any way of getting out of because there was nothing set up anywhere in Australia at his stage for men,’ Peter says. ‘When I was trying to come to terms with all these side-effects I had to really search and find out who I am. Part of this quest was to answer the question “what does it mean to be a man?”,’ Peter says. Prostate cancer was the stimulus for the men’s health movement, and Peter was at the front of it.

‘There’s a great loss involved. You go through the grief process of denial, anger and depression, and eventually you come to acceptance. With insight, you go through a process psychologists call post traumatic transformational growth, a situation where you gain some wisdom concerning life and how it relates to you. Cancer doesn’t change you, it reveals you. It gives you a chance to recalibrate your belief systems, your standards and values. You emerge as if from a chrysalis.’ From that growth Peter set about founding the first support group for prostate cancer in Queensland, which went on to become the largest such group in Australia. It lay the foundations for a network which now ensures the thousands of men diagnosed with prostate cancer— typically about 19,000 each year in Australia—do not go through the experience alone as he did.

As an elite sports physiotherapist, Peter called on the help of his own expertise and redesigned aspects of his life as a dynamic business plan. Part of this involved paying attention to what he calls ‘Big Red’— rest, exercise and diet. Rest, he says, means you take holidays, you design your day so that you do creative things and express yourself through mediums such as art or sculpting, the latter of which Peter took up (he also plays the saxophone and sings in operatic productions).

And rest also means finding time to meditate or for deep relaxation. Exercise is a combination of pelvic floor and abdominal muscle work that includes 400 abdominal crunches a day and combinations of running, boxing and swimming six days a week for 45 minutes. Diet is based on the Mediterranean fare of fish and chicken, fresh fruit and vegetables, very little red meat, and nuts and olive oil, among others.

His experiences led Peter to pen the book Conquering Incontinence, which is now widely used as an essential guide by prostate cancer support groups. To celebrate, six years after diagnosis, at age 60, Peter climbed Mt Kilimanjaro in Africa. He is now a director of Cancer Council Queensland, and Sharon Cohr’s sculpture stands in the annexe and inspires all cancer survivors to believe that anything is possible. Peter was also acknowledged for his distinguished service by way of an award from the Australian Prostate Cancer Foundation, among many other accolades he has received throughout his career and life. These include being appointed as a Member of the General Division of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2002 and being awarded the commemorative 2000 Australian Sports Medal for his achievements in sport. Peter’s ongoing interest in pelvic conditions led to another book, Pelvic Pain, being published in 2014. Peter is also a member of the APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health group and teaches men’s health through classes entitled Mastering the Martians.

‘We have really good classes, we have about 40 physios along, and we teach them male behaviour, and at the end of it they understand a lot more about what males are. Since we’ve been doing that, a lot more physios, both men and women, are now treating men with prostate cancer before and after, so my need has dropped off tremendously there. This has allowed me to concentrate completely, or almost completely, on pelvic pain,’ Peter says. He is recognised as an international leader on the musculoskeletal approach to treatment and, as such, a revised edition of Pelvic Pain is expected to be published soon.

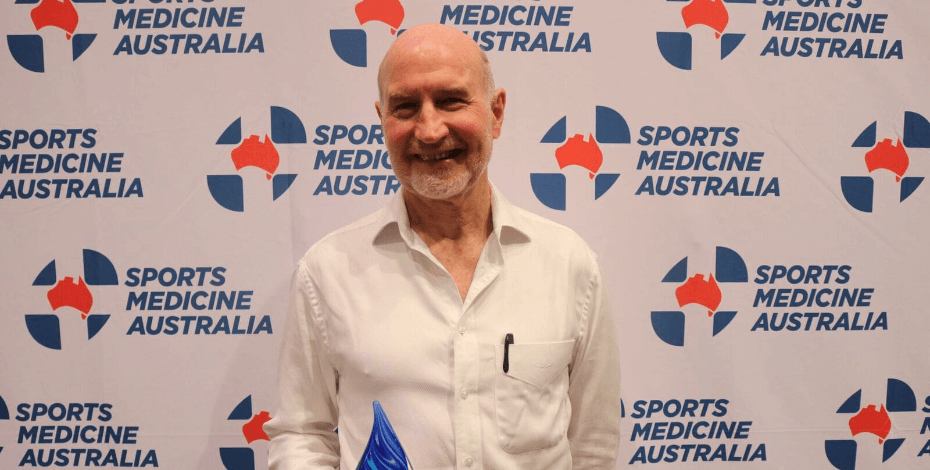

Peter is also relishing working at his private practice in Toowong, Brisbane, which he opened after graduating in 1967. In that time, Peter has also been heavily involved in APA groups (he helped start the first private practitioners’ group, now the APA Business group) and on various subcommittees. He recently celebrated 50 years as a physiotherapist and says an important part of his passion for the profession has been his involvement with the APA and other professional bodies such as Sports Medicine Australia (SMA). Peter was cofounder of the Queensland branch of SMA in 1970. In fact, Peter considers involvement at all levels is one of the main ingredients for achieving professional longevity.

Peter looks forward to going in to work every day, and at each lunchtime he shuts the door at his private practice so that he can meditate for 20 minutes. ‘You have to create a meaningful life, life doesn’t always reveal a meaningful purpose to you. You’ve got to go and search for it.’

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.