What is pain sensitivity and why does it matter?

In this first instalment in a series on pain sensitivity, Darren Beales FACP and Tim Mitchell FACP provide an overview of what pain sensitivity is and why it’s an important concept to understand in clinical practice.

Movement and function are key domains of physiotherapy and pain often gets in their way. For many physiotherapists, addressing pain to optimise movement and function is core business.

Pain is necessary. Pain is complex. The International Association for the Study of Pain provides this definition of pain: ‘An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.’

The sensory nature of pain and the emotional aspect of pain are complex. It is this complexity that makes it fun for physiotherapists to know about pain, think about pain, talk about pain and, ultimately, help our clients manage their pain.

One idea about pain that has become popular is pain sensitivity. The term alone can cause hours of debate. We don’t mind this term. Laypeople get it.

Figure 1.

Search PubMed and you will find that it is a populist term in the literature (eg, pain sensitivity had 15 times more hits than central sensitisation at the time of writing). Is it technically correct? We are happy to leave that debate to the pain scientists.

So, what is pain sensitivity? We have recently offered this definition: ‘Pain sensitivity in the clinical context can be considered as a term used to encompass the phenomena that some people’s experience and perception of pain is enhanced (or reduced) beyond that of others.’ Vague, perhaps.

However, think of someone with allodynia, where pain is provoked by what would normally be considered a non-painful stimulus. Look at this video of someone with allodynia on one side of their back. Think again about the definition just provided.

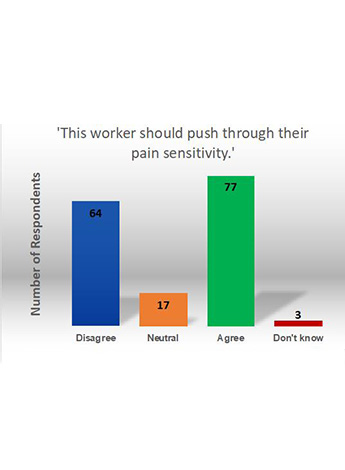

We showed this video to a room of 161 people involved in the management of people with work-related pain.

We told them, ‘A worker has non-specific spinal pain (no significant MRI findings) that presents as being dominantly non-mechanical. They have high pain sensitivity—allodynia with light touch, hyperalgesia with sharp and cold, pain flare-up with light physical activity, minimal effective strategies for pain relief.

We said, ‘The worker needs to push through their pain to increase their physical capacity.’ We asked them if they agreed or disagreed. See Figure 1 for the range of responses. There was clearly a divide in opinions on how this person should approach their pain. Perhaps this reflects the complexity of pain and pain sensitivity.

Is there a right answer? Well, stick with us through this six-part series and at the very least you will be able to make an informed decision.

Keep in mind that pain sensitivity is not relevant in many patient presentations, but it should be (at least briefly) considered in all presentations.

Who is this for?

Everyone. We feel that any physiotherapist who has anything to do with pain should understand pain sensitivity. Clinicians need to understand it.

Pain sensitivity is known to be a factor in musculoskeletal conditions like back pain, neck pain, shoulder pain and knee pain. It is an important factor to consider in pelvic pain disorders. It is also known to have an impact on surgical outcomes.

Pain sensitivity can be a feature in neurological disorders (eg, shoulder pain after a stroke) and respiratory disorders (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis). That covers the patients of just about everybody working in clinical practice.

This series will focus on helping clinicians understand pain sensitivity. However, administrators and policymakers should also understand it. For example, the development of care pathways for health disorders might require different considerations for those who have significant pain sensitivity as a prominent contributing factor in their presentation.

Person-centred care

We champion the concept of person-centred care that takes a holistic, biopsychosocial approach to pain disorders. Pain sensitivity is only part of the equation.

For a broader contextualisation of pain sensitivity within a person-centred approach, click here to access the Musculoskeletal Clinical Translation Framework: From Knowing to Doing.

This is now embedded in the curriculum of more than 10 universities internationally, so it is probably a reasonable resource for understanding the broader context. Yes, it has musculoskeletal in the title. But we feel it is relevant to all areas of practice.

Why should clinicians consider pain sensitivity?

There are contradictory findings in research related to the effect of pain sensitivity. For instance, pain sensitivity has been linked to higher levels of reported pain and disability, though this is not always the case.

A number of systematic reviews have failed to establish consistent links of this nature. Despite these findings, there are various ways in which understanding pain sensitivity might help both clinician and patient.

A. Pain sensitivity can alter a person’s response to treatment. There is an emergent body of literature examining the extent to which pain sensitivity can be a treatment effects modifier. For example, pain sensitivity can negatively influence the effect of lumbar spine surgery and knee surgery. It can also negatively affect the response to the implementation of guideline-based physiotherapy for knee osteoarthritis and whiplash. Understanding whether pain sensitivity is a significant factor in a person’s presentation may be useful for predicting how they might respond to treatment.

B. Understanding pain sensitivity can help a patient make sense of their overall condition. When recovery extends well beyond expected healing times, or when there is persistent pain despite no evidence for trauma or tissue damage, patients may struggle to understand what might be driving their pain. When pain sensitivity is a significant factor contributing to their condition, education about it can significantly help people understand what is going on with their bodies.

C. Patients can be subgrouped based on their sensory profiles. While it is not always the case that subgroups of people with heightened pain sensitivity features have higher levels of pain and disability, we believe that awareness of these subgroups can help clinicians recognise the spectrum of pain sensitivity presentations and consider the impact of pain sensitivity at an individual level.

D. Pain sensitivity might provide insight into a patient’s prognosis. Some studies have shown that pain sensitivity in the acute phase of an injury can predict delayed recovery (eg, in acute whiplash). Understanding the presence and relevance of pain sensitivity early on may help prioritise care needs.

Next time

In next month’s article, we will discuss a pragmatic way for clinicians to consider pain sensitivity during the client interview.

Resources

Like to hear Tim and Darren casually chat about pain sensitivity? Click here.

Like to read about our take in a scientific journal? Click here for Beales et al. ‘Masterclass: A pragmatic approach to pain sensitivity in people with musculoskeletal disorders and implications for clinical management for musculoskeletal clinicians.’ Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 2021.

Like some useful patient education resources? Click here, here and here.

Want the bigger picture? Click here for more.

Want the pain science? Click here.

Like something short and fun? (Yes, it’s Tim and Darren again.) Click here.

>> Darren Beales is a Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist (as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2008) and a director at Pain Options in Perth, WA. As a Senior Research Fellow at Curtin University, Darren’s research in clinical pain is broad, covering the mechanistic understanding of clinical pain through to efforts to enhance the management of persistent pain and implementation of knowledge into practice.

>> Tim Mitchell is a Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist (as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2007) and a director of Pain Options. Tim has completed a PhD in the area of low back pain and has a special interest in the translation of logical reasoning into clinical practice. He holds positions with the Australian Physiotherapy Council and the Australian College of Physiotherapists.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.