5 facts about … pelvic pain

APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health group members Amanda Lee, Tarryn Lawrence, Tory Toogood, Rachel Andrew and Sarah Walsh contribute five discussion points about pelvic pain, and offer examples of how physiotherapy intervention can benefit patients experiencing a range of pelvic pain presentations.

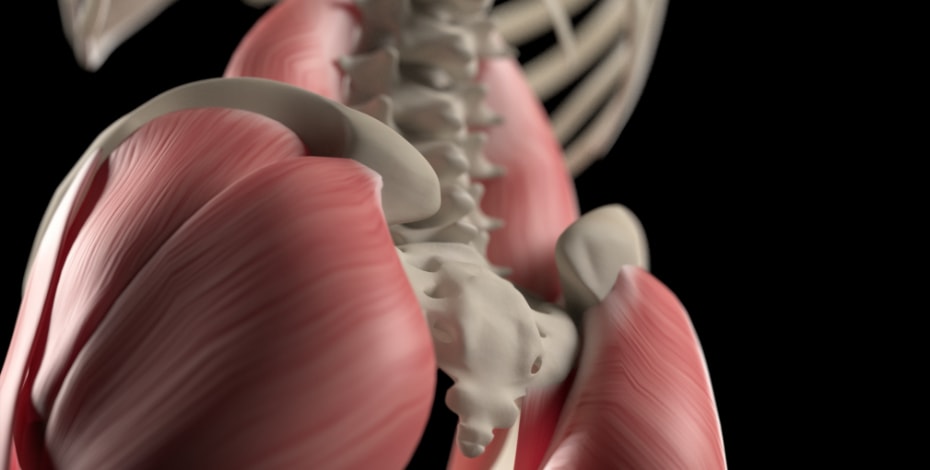

1. Coccydynia—a pain in the buttocks?

Coccydynia is defined as pain in the region of the coccyx. A contributing factor is abnormal mobility of the coccyx, which triggers a chronic inflammatory process. Often there is a history of an associated traumatic event.

People with an increased anterior angulation of the coccyx are more prone to pain than those with a slight forward curve. While this condition may affect individuals of all ages and gender, the prevalence is five times greater in women than in men.

Non-surgical management is considered the gold standard for treatment of coccydynia. As such, physiotherapists working in pelvic health are well placed to treat this condition. Management includes education about less sitting time, advice on suitable chairs and cushioning, massage of muscles that attach onto or close to the coccyx, mobilisations, postural adjustments and potentially local injection of steroids or anaesthetics. Coccygectomy is for patients who fail to get relief from conservative measures and those who show evidence of advanced coccygeal instability or spicule formation.

Manual therapy involves release of the gluteal muscles and pelvic floor muscles, externally first, and if indicated, internally. Mobilisations help to release any stiffness between the sacrum and the innominate, allowing for optimal sacral movement. Global or local muscle imbalances contributing to abnormal sacral tilt are corrected through strengthening or stretching. Specific coccyx mobilisations internally may also be administered if indicated. In most cases, physiotherapy is very successful in the management of coccydynia.

References

Ravi et al. (2008). Coccydynia. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 1:223-226

Fogel et al. (2004). Coccygodynia: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 12:49-54

Maigne et al. (2000). Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 25:3072-79

Postacchini et al. (1983). Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. J Bone Joint Surg. 65:1116-24

2. Physiotherapy can assist people with bladder pain syndrome

Bladder pain syndrome (BPS), also called interstitial cystitis, is a persistent pain condition affecting the bladder. It is characterised by a feeling of pain and/or pressure in the area of the bladder, which gets worse on filling and improves once the bladder empties, along with lower urinary tract symptoms, which may include frequency, urgency, and nocturia. BPS is not a bladder infection, but many people with BPS describe having recurrent urinary tract infections. This is often a flare of their symptoms—when their urine is tested there is rarely an infection.

People with BPS also frequently have penetrative pain and problems with their bowel and sexual function. BPS prevalence rates vary according to diagnostic criteria; however, it is estimated to affect 2–17 per cent of the general population, more commonly in females.

People with BPS generally require multidisciplinary input (eg, urology/urogynaecology, GP, psychology, dietetics) including physiotherapy. Physiotherapists with training in women’s, men’s and pelvic health are able to assist people with BPS in a number of ways. This may include assessment of a bladder diary, education regarding fluid intake and avoidance of bladder irritants, and assessment of the pelvic floor muscles to determine whether they are contributing to symptoms. It is quite common for people with BPS to have pelvic floor muscle overactivity, which has also been shown to benefit from physiotherapy intervention.

References

Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia website

Davis, N. F., Gnanappiragasam, S., & Thornhill, J. A. (2015). Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: the influence of modern diagnostic criteria on epidemiology and on Internet search activity by the public. Translational andrology and urology, 4(5), 506.

Pelvic floor muscle hypertonicity can be a component of pelvic and hip musculoskeletal conditions

The pelvic floor muscles (PFM) and other muscles inside the pelvis can be a source of pain, and a source of referred pain. There have been case reports of combined gluteal, proximal hamstring, groin and pelvic pain, leading to a conclusion that there can be a relationship between lumbopelvic and lower limb movement patterns and hamstring, posterior thigh, buttock and pelvic floor disorders.

Women with hip labral injuries that aren’t responding well to standard physiotherapy management may also have concomitant pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, particularly overactivity into the obturator internus and iliococcygeus. Such women may not report any change in bladder or bowel behaviour, nor dyspareunia, but on physical examination from a competent pelvic health physiotherapist, may demonstrate signs of tenderness to palpation, increased tone and reproduction of ‘deep pain’ symptoms on the affected side.

Usually we would also find this higher tone PFM has difficulty relaxing, relatively poor strength, shows poor endurance, poor timing and poor coordination. Treatment focuses on muscle relaxation and lengthening, general pelvic/hip stretching, improved awareness of any ‘gripping’ habits, and soft tissue mobilisation. It is worthwhile for musculoskeletal and sports physiotherapists to work with a pelvic floor physiotherapist for some of those tricky hip patients, to exclude a pelvic floor contribution.

References

Butrick CW (2009) Pelvic floor hypertonic disorders: identification and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin N AM 36:707-722

Gyang, A., Hartman, M., & Lamvu, G. (2013). Musculoskeletal Causes of Chronic Pelvic Pain. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 121(3), 645–650

Podschun L et al (2013) Differential diagnosis of deep gluteal pain in a female runner with pelvic involvement: A case report

Weiss JM (2001) Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. J Urol.166:2226- 2231

4. Pelvic floor physiotherapy can reduce painful periods

Around 80 per cent of Australian women experience period pain or dysmenorrhoea at some time in their lives, but it is not normal to have to miss school, work or sport. Severe dysmenorrhea can have a huge impact on quality of life, relationships and sexual function.

Primary dysmenorrhoea is painful menstrual periods, without underlying disease. Secondary dysmenorrhoea is due to an underlying disease, such as endometriosis, and can present as either new symptoms or a change in symptoms.

Women may not disclose painful periods due to embarrassment, taboo or an assumption that it is normal. Dysmenorrhoea can be subject to wind up, sometimes resulting in persistent pelvic pain. Due to the pelvic floor muscles’ close relationship to oestrogen and two dips in oestrogen during the menstrual cycle, other pelvic floor symptoms such as incontinence or prolapse (heavy dragging sensation) can worsen.

Treatment options for dysmenorrhoea offered by pelvic health physiotherapy include stretching of the external muscles which attach to the pelvic girdle, pelvic floor down training, internal soft tissue manipulation and desensitisation, relaxed breathing and mindfulness, pessary to support prolapse, TENS, pain neuroscience education, pelvic anatomy and menstrual cycle education, and support with lifestyle habits to reduce inflammation.

References

LR Gerzon et al (2014) Physiotherapy in primary dysmenorrhoea: literature review. Rev Dor Sao Paolo 15(4)290-5

AK Subasinghe et al (2016) Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea, and management options reported by young Australian women. Australian Family Physician 45(11) 829-834.

https://www.myhormonology.com/learn/female-hormone-cycle/

5. Painful intercourse occurs in women and men of all ages

Dyspareunia is the term used for painful intercourse in women and men. This pain can be experienced before, during, or after intercourse. It can be further defined as primary (occurs at initial intercourse) or secondary (occurs after a period of pain-free intercourse). For women, it can be also defined as superficial (localised to the vulva or vaginal entrance) or deep (inside the vagina or lower pelvis).

It is thought that 20 to 50 per cent of all women and one to five per cent of men will experience dyspareunia in their lifetime. Many women and men do not seek help; therefore, unless directly asked, people will often not reveal this pain. It can have many physical and psychosocial consequences, both for the individual and their partner.

Dyspareunia is the ‘symptom’ for which there are many potential physical and/or psychological causes. A multidisciplinary approach is therefore usually needed to assess and manage it. Pelvic floor physiotherapy can be important in educating about pain science and promoting active self-management, for women and men.

References

Basson, R., Berman, J., Burnett, A., Derogatis, L., Ferguson, D., Fourcroy, J., Goldstein, I., Graziottin, A., Heiman, J., Laan, E. and Leiblum, S., 2000. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. The Journal of Urology, 163(3), pp.888-893.

Doggweiler, R., Whitmore, K.E., Meijlink, J.M., Drake, M.J., Frawley, H., Nordling, J., Hanno, P., Fraser, M.O., Homma, Y., Garrido, G. and Gomes, M.J., 2017. A standard for terminology in chronic pelvic pain syndromes: A report from the chronic pelvic pain working group of the international continence society. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 36(4), pp.984-1008.

Engeler, D., Baranowski, A.P., Borovicka, J., Cottrell, A.M., Dinis-Oliveira, P., Elneil, S., Hughes, J., Messelink, E.J. and de C Williams, A.C., 2018. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain, 2018. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Copenhagen 2018, The Netherlands, viewed 25 April 2019, http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/.

Pitts, M., Ferris, J., Smith, A., Shelley, J. and Richters, J., 2008. Prevalence and correlates of three types of pelvic pain in a nationally representative sample of Australian men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(5), pp.1223-1229.

Sorensen, J., Bautista, K.E., Lamvu, G. and Feranec, J., 2018. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: A clinical review. Cureus, 10(3). pp.1-11.

Amanda Lee, APAM, is a member of the Victorian APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health Group committee. She works clinically at The Melbourne Sports Medicine Centre and Pelvic Health Melbourne.

Tarryn Lawrence, APAM, is the chair of the Queensland Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health committee. She currently works as a physiotherapist in an advanced role in the Pelvic Health Clinic at Logan Hospital.

APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health Physiotherapist Tory Toogood has much experience in both pelvic health and sports physiotherapy, both personally and professionally. She works exclusively in private practice, including consulting to gynaecologists and colorectal surgeons.

APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health Physiotherapist Rachel Andrew is a women’s health and continence physiotherapist who works in Hobart. She works in a group practice and loves treating pelvic pain.

APA Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health Physiotherapist and APA Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist Sarah Walsh (nee Propsting) works at Flex Rehabilitation Clinic and the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Adelaide, South Australia.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.