Physiotherapy management of sciatica

The April issue of the Journal of Physiotherapy includes an Invited Topical Review on physiotherapy management of sciatica. Here is a Q&A with Professor Raymond Ostelo.

Does everyone agree on the definition of sciatica and how common it is?

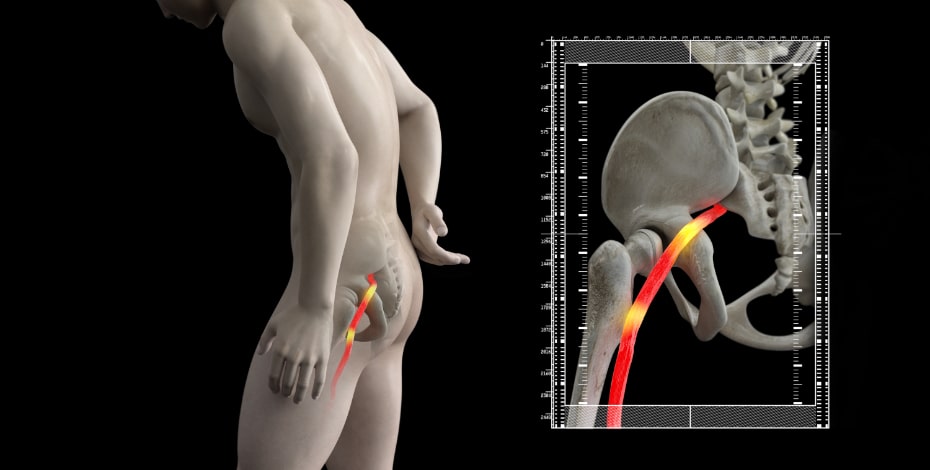

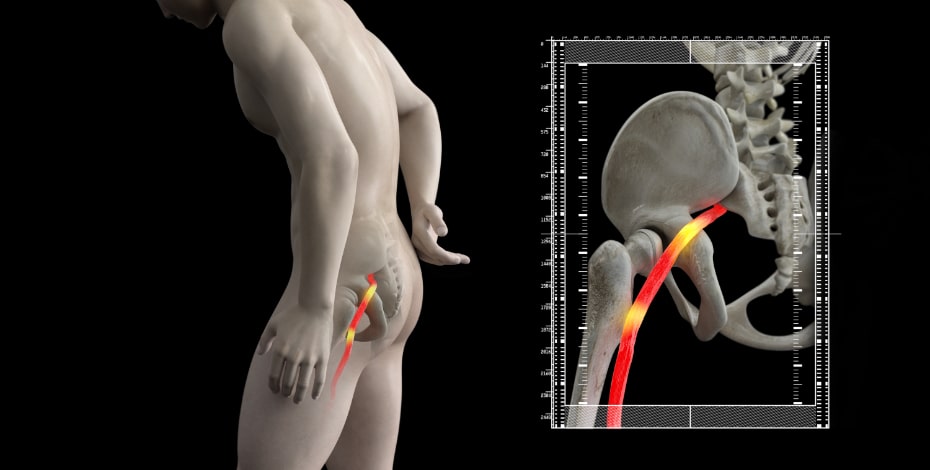

The term is not used consistently in the literature or in clinical practice. Some use it for any type of leg pain or any type of combination of back and leg pain. In most cases sciatica is used to describe pain that radiates from the buttock downward along the course of the lumbosacral nerve roots. An alternative term that is often used is lumbar radiculopathy. Sciatica occurs frequently, although the estimates come with uncertainty. In Western countries the incidence has been estimated to be five per 1000.

What causes it?

Sciatica is caused by a herniated lumbar disc where the nerve root is compressed by disc material that has ruptured through its surrounding annulus. Rarer causes include spondylolisthesis, lumbar stenosis, foraminal stenosis and malignancy. The common denominator is that the lumbar nerve root is compressed—but mainly the combination of pressure-related, inflammatory and immunological processes seems to be the important cause of sciatica.

How should physiotherapists manage a patient with sciatica?

Patients should be provided with adequate explanation of the nature and prognosis of sciatica. Additionally, it should be discussed with the patient that imaging is not recommended unless there are good reasons to do so (suspicion of cauda equina syndrome or fractures). This is an important topic to discuss as imaging tests are often performed because the patient feels it should be done, or to reassure them.

What about the advice to stay active?

International clinical guidelines include the ‘encouragement to stay physically active’ and bed rest is not recommended, except maybe for the first one or two days if pain is really disabling. Activities mainly include activities of daily life that are important to the patients themselves.

And other interventions?

Exercise therapy and spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) are two important interventions that could be considered. But for both interventions the evidence is not overwhelmingly strong, which leads to some differences in recommendations for different clinical guidelines. One clinical guideline recommends supervised exercise therapy (eg, directional exercises, motor control exercise, nerve mobilisation, or strength exercises), but no specific recommendations for a type of exercise treatment was made. For clinical practice, that means that the type of exercise should be aligned with the specific complaints and wishes of the patient, and the specific training of the physiotherapist. In contrast, a guideline for GPs recommends exercise therapy only when patients have complaints for more than six to eight weeks—and these complaints have not considerably improved over this period.

Are medications used?

Medications are used, despite the fact that the evidence tells us it is unlikely these are effective. There is only some evidence that might suggest that in acute sciatica corticosteroids and NSAIDS might marginally improve pain in the short term.

Physiotherapists also get involved in rehabilitating patients after surgery?

Yes, they do. In general, it is not necessary to start immediately after surgery with these rehabilitation programs. For patients who have not improved substantially four to six weeks after surgery, there is some evidence that suggests that physiotherapy is associated with better outcomes immediately after treatment compared to no treatment on pain and physical functioning.

Where to from here?

One of the challenges is integrating clinical findings, results from physical tests, and biomarkers into one classification system—with a specific focus on primary care, where the majority of sciatica patients are screened and treated.

Therefore, some important issues need to be addressed. The role inflammation plays in sciatica, and if there is a certain stage in the course of (developing) sciatica at which this mechanism may be more prominent, should be explored in more depth. There is also an urgent need to reach consensus on definitions for leg (and back) pain in an unambiguous manner in order to overcome the current confusion regarding descriptors for radiating leg pain. If these issues are addressed, research can focus on the classification system with the ultimate aim to get the patient the right treatment from the beginning.

>> Raymond Ostelo is professor of evidence-based physiotherapy. He is one of the program directors of the Amsterdam Movement Sciences Research Institute and is leading the musculoskeletal research section of the department of Health Sciences at Vrije University in Amsterdam.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.