Five facts about disorders of the temporomandibular joint

Dr Rod McLean of the APA Musculoskeletal national group presents five discussion points about the relationship between the temporomandibular joint and temporomandibular disorders, including aetiology, subtypes and diagnosis.

1. TMD has multiple effects and causes

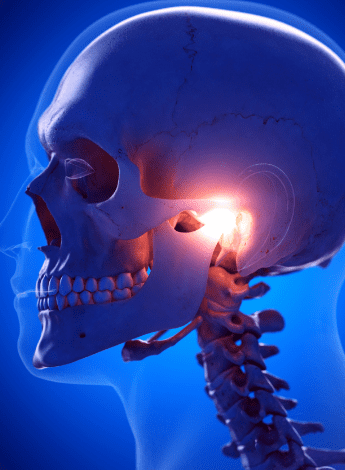

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is the articulation of the lower jaw (mandible) with the temporal bones of the skull.

Normal movement of the TMJ allows for a range of important bodily functions such as eating, drinking, laughing and breathing—alongside numerous other vital tasks.

If a temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is present, several of these important processes may be affected.

The aetiology of TMD is often multifactorial; causes can stem from biological factors, arise from the surrounding environment or emerge due to the individual’s mental and cognitive health (Gauer & Semidey 2015).

Signs and symptoms may include pain, headaches, clicking and locking as well as a reduced mouth opening (Durham 2015, Shaffer et al 2014a, Dinsdale et al 2020, Dinsdale et al 2021).

TMD affects up to 15 per cent of adults, with a peak incidence between 20 and 40 years of age (Magnusson et al 2000, Lim et al 2010, Goncalves et al 2011, Maixner et al 2011, Sharma & Ohrbach 2018).

In comparison to men, women have disproportionately high rates of TMD (LeResche 1997, Sharma & Ohrbach 2018).

There are a number of other pain conditions associated with TMD including chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, autoimmune disorders and sleep apnoea (Lim et al 2010, Kleykamp et al 2022).

An estimated half of TMD cases arise from issues relating to musculature or joint structures (Gauer & Semidey 2015).

It is a persistent condition causing concurrent distress and interference in daily life (Penlington et al 2022).

2. There are multiple subtypes of TMD

In order to distinguish and classify the subtypes of TMD, it is necessary to reference the diagnostic criteria (Schiffman et al 2014).

The subtypes of TMD have been delineated according to contributing factors. For example, an Axis 1 diagnosis recognises the role of biological contributors in the development of TMD.

By contrast, an Axis 2 diagnosis emphasises the role of psychological and behavioural factors in the development of the condition (Schiffman et al 2014).

It is important to note that Axis 1 and Axis 2 diagnoses are not mutually exclusive.

Through identifying TMD’s subtypes, clinicians are able to take a more targeted approach when managing the condition.

3. Physiotherapists are well placed to diagnose, assess and manage TMD

The presence of musculoskeletal signs and symptoms and physical impairments in TMD means that physiotherapists can play a crucial role in the diagnosis, assessment and management of patients with the condition.

Treatment of TMD is based on a biopsychosocial model of care, which physiotherapists deliver through a multimodal management approach.

This might include manual therapy, massage and therapeutic exercise as well as patient education and relaxation strategies (Shaffer et al 2014b).

Surgery is rarely required to manage TMD.

Because the majority of TMD cases can be managed conservatively, physiotherapists are afforded great scope to be the practitioners of choice for assessment and management of TMD (Durham 2015, Scrivani et al 2008).

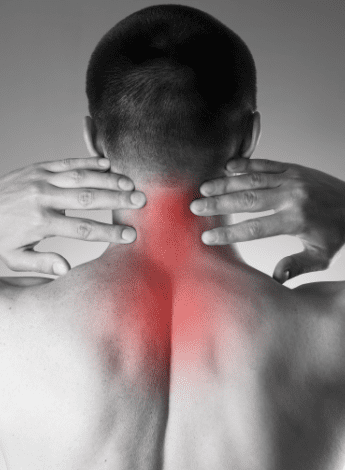

4. The upper cervical spine should be a diagnosis of exclusion in TMD

There is well-documented evidence for the upper cervical spine referring to the jaw and facial region through the shared

trigeminocervical nucleus, which has efferent input from and afferent output to the upper three cervical joints and the regions supplied by the trigeminal nerve.

This has been explored through pain mapping of the cervical zygapophyseal joints (Cooper et al 2007).

Through careful questioning and assessment of the upper cervical spine, an upper cervical contribution can be determined.

The presence of positive joint signs with referral to the TMJ region would indicate that this region should be explored with treatment.

A systematic review explored the presence of cervical musculoskeletal disorders in TMD (De Oliveira-Souza et al 2020).

However, there were only a small number of studies and low sample sizes within the studies.

As a result, the role of the upper cervical spine needs to be proven or disproven through careful examination.

5. Psychological factors and comorbidities contribute to TMD

Social and emotional factors are commonly associated with the aetiology of TMD and physiotherapists need to consider the role of psychological factors in TMD patients.

Factors such as stress and anxiety may be involved in the perpetuation of a patient’s TMD or may be a comorbid condition.

For example, anxiety and depression are often associated with TMD (Brochado et al 2018). People with myofascial pain (one

of the most common subtypes of TMD) may be more likely to exhibit symptoms of anxiety and depression than those with other subtypes of TMD (Reis et al 2022).

In addition to questions in the patient interview, screening questionnaires such as the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 are helpful for quantifying these domains and their use is encouraged.

As musculoskeletal practitioners, we should consider whether we have the skills to manage this component of a patient’s presentation or whether trained mental health professionals (eg, psychologists) should be called on to assist in managing patients with TMD.

Psychologists offer education and coping strategies to help patients develop new cognitive and behavioural skills so that they can reflect on and manage their symptoms (Penlington et al 2022).

This enables patients to reduce pain and disability and lessens the distress associated with pain (Penlington et al 2022).

A Cochrane systematic review described low-certainty evidence that cognitive behavioural therapies may decrease pain intensity more than alternatives at long-term follow-up (Penlington et al 2022). However, more research is required in relation to this.

While TMD is common and there are several subtypes, physiotherapists are well placed to manage TMD from a biopsychosocial perspective.

A thorough patient interview, history and physical examination and the use of questionnaires (in order to delineate psychological contributors) are all essential features for diagnosis.

Quick links:

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.