Five Facts about osteosarcopenia in gerontological physiotherapy

Hannah Sharma, Hannanja van der Veer, Caitlin McDonald and Alison Reading of the APA Gerontology national group present five discussion points about osteosarcopenia in older adults and the importance of screening and exercise in physiotherapy management of the condition.

1. Osteosarcopenia is an emerging ‘geriatric giant’

Osteosarcopenia is the concurrent presence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia.

Osteoporosis is low bone mass and structural deterioration of the bone, while sarcopenia is the loss of muscle mass and function (Clynes et al 2021).

Through longevity, the increase in the ageing population and a lifestyle of minimal physical activity, the health and economic implications of the condition are expected to rise.

Osteosarcopenia is now being referred to as a ‘geriatric giant’ (Duque 2021).

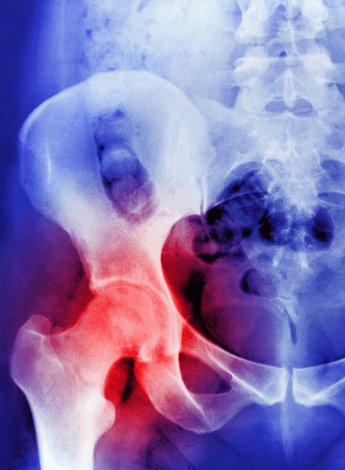

Osteoporosis and osteopenia are defined as structural deterioration of the bone leading to reduced bone density and strength.

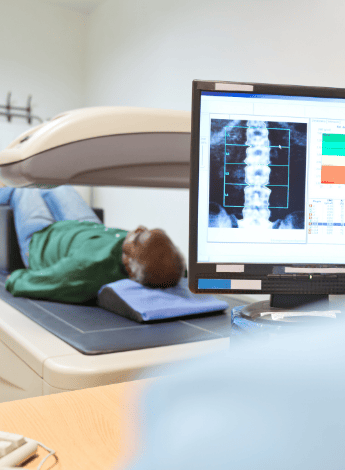

The gold standard for assessing bone density is a DEXA scan.

World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis and osteopenia are based on bone mineral density scores, in which a T-score of -1 or less is indicative of osteopenia and a T-score of -2.5 or less is indicative of osteoporosis.

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People defines sarcopenia as loss of muscle mass, reduced muscle strength and poor physical performance.

This definition has been updated to emphasise the loss of muscle strength as measured by reduced hand grip strength and the sit-to-stand test.

Severe sarcopenia is associated with poor physical performance (Cruz-Jentoft et al 2019).

2. Osteosarcopenia is a subset of frailty

Osteosarcopenia is associated with lifestyle-related risk factors such as poor nutrition (including low protein intake and low levels of calcium and vitamin D) and low levels of physical activity (Kirk et al 2020).

This can create a cycle of undernutrition and low energy expenditure leading to even lower activity levels due to poor muscle strength and low bone mass (Theou et al 2020).

Other lifestyle-related factors include smoking and alcohol consumption.

Comorbid conditions such as osteoarthritis and cancer are associated risk factors, along with endocrine dysfunction (eg, insulin insensitivity).

Non-modifiable risk factors include older age, female gender and Caucasian race (Kirk et al 2020, Park et al 2021).

The pathogenesis of osteoporosis and sarcopenia is also interrelated (Park et al 2021).

Bones and muscles provide structural support to the body and are intricately related on mechanical, chemical and molecular levels.

Various plausible theories have been put forth to explain the concurrent occurrence of the two conditions.

Mechanostat theory proposes a lack of muscle forces on the bone, resulting in reduced bone formation activity and eventually bone loss.

Bone–muscle cross-talk theory relies on the chemical connections between bone and muscle via hormones.

Inflammaging theory discusses the role of low-level inflammation and molecular connections through cytokines as the pathological mechanism of osteosarcopenia (Hirschfeld et al 2017).

3. Early recognition and intervention improve outcomes

Older people with osteosarcopenia represent an important subset of frail individuals at higher risk of poor health outcomes if the condition is left unmanaged.

They have impairments in balance and mobility and are at higher risk of falls and fractures (Park et al 2021).

The presence of osteosarcopenia in older adults who sustained a fracture post-fall was associated with higher mortality one year later compared to non-osteosarcopenic controls (Kirk et al 2020).

Older people with osteosarcopenia also have lower functional capabilities (Sepulveda-Loyola et al 2020), which may limit activities of daily living and reduce independence.

Osteosarcopenia can exacerbate depression and disability in older adults living in the community and is associated with a higher risk of institutionalisation (Park et al 2021).

A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for non- pharmacological management of osteoporosis recommends early detection and intervention (Coronado-Zarco et al 2019).

It has been suggested that DEXA analysis should look at bone mass as well as muscle mass (Park et al 2021).

Early screening for decreasing bone density and muscle loss in younger individuals (ie, people in their 40s) may allow for individualised risk factor reduction and management programs to be implemented before functional decline occurs, mitigating the development of osteosarcopenia (López-Teros et al 2021).

4. Multidisciplinary input is vital for holistic and individualised management

It is recommended that screening for osteosarcopenia be included in a comprehensive geriatric assessment.

The presence of osteoporosis must trigger screening for sarcopenia and vice versa.

Underlying causes of osteoporosis and sarcopenia should be explored (Kirk et al 2020).

The role of the multidisciplinary team is central because individual risk factors need to be identified and managed and targeted investigations undertaken (Pilotto et al 2017).

High-risk clients with multiple risk factors for osteoporosis and sarcopenia should be referred to a specialised multidisciplinary care clinic run by a geriatrician (Hassan & Duque 2017).

First-line prevention and treatment for osteosarcopenia is a healthy lifestyle and regular exercise.

Recommendations may include smoking cessation; alcohol restriction; adequate intake of vitamin D, calcium and protein; and pharmacotherapy.

In addition to physiotherapists, team members include geriatricians, dietitians and occupational therapists.

Psychologists may also be involved because there is a high association of depression with osteosarcopenia.

If a patient cannot access a specialist clinic, they should be referred for physiotherapy or exercise physiology for management of their falls risk (Hassan & Duque 2017).

The SARC-F tool—a self-reported, five-item questionnaire—has been validated for use in hospitals and community settings to screen for sarcopenia (Malmstrom & Morley 2013) and is suggested as part of an osteosarcopenia screening (Huang et al 2023).

5. Physiotherapists play a key role in managing osteosarcopenia

Physiotherapy management of osteoporosis and sarcopenia must include interventions that target bone mineral density and increase muscle strength and physical performance, along with balance training and falls risk reduction.

Multi-component exercise programs including osteogenic exercises, resistance training and balance training have been shown to be effective and safe in older adults with osteoporosis (Giangregorio et al 2014) as well as postmenopausal women (Watson et al 2018).

Not all exercises have an osteogenic effect.

Evidence-based recommendations for managing osteoporosis include high-intensity, weight-bearing, impact-loading exercises (Beck et al 2017).

Short bursts of dynamic and cyclical loading with high strains to the bone are effective in creating an osteogenic effect, while progressive resistance training at high intensity has been shown to improve muscle strength, function and physical abilities.

Such exercises modulate the pathophysiology of sarcopenia and can delay the onset as well as reverse sarcopenia in older adults (Talar 2019).

A supervised resistance training program is safe and effective for older adults and no serious adverse outcomes have been reported (Atlihan et al 2021).

Resistance training has been shown to increase lumbar bone mineral density over 12 months and maintain hip bone mineral density over 18 months.

It may also increase muscle strength and quality in osteosarcopenic individuals.

Moderate–high intensity, supervised resistance training should therefore be recommended for older adults living with osteosarcopenia.

>> Hannah Sharma APAM is a physiotherapist and educator with 17 years of clinical experience across public, private, community and disability settings. Hannah’s PhD focuses on supporting sustained engagement in exercise for older people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Hannah is the chair of the Victorian branch of the APA Gerontology national group.

>> Hannanja van der Veer APAM is a senior physiotherapist working for the Tasmanian Health Service on a slow stream rehabilitation unit with clients with cognitive and/or mental health problems as well as working as a domiciliary physiotherapist. Hannanja is the chair of the Tasmanian branch of the Gerontology group.

.>> Caitlin McDonald APAM is an experienced physiotherapist working in community aged care who leads a multidisciplinary team delivering care in the community. Caitlin is a strong advocate for physiotherapy for older adults and is the chair of the Western Australian branch of the Gerontology group.

>> Alison Reading MACP is a Titled APA Gerontological Physiotherapist who works as a senior physiotherapist within the Western Australian Department of Health. Alison completed her Master of Applied Gerontology at Flinders University and is a member of the Gerontology group’s Western Australian committee.

Quick links:

Course of interest:

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.