Former ballet dancer lands on his feet

After discovering the world of classical ballet as a boarding school student in Adelaide and going on to train at the New Zealand School of Dance, Jeremy Hunt, APAM, realised his fascination with body movement and his understanding of the dancer’s life had far wider applications.

Listening to an explanation about ankle ligaments may not sound like a life-changing event but it was the beginning of a deep fascination of human anatomy and physiology for Jeremy Hunt. As a young student with the New Zealand School of Dance, and a ballet dancer who had experienced injury, Jeremy was listening with nothing short of awe, as the school’s physiotherapist, Susan Simpson, rattled off names of the bones and ligaments of the foot and their functions.

‘I was just fascinated by how many bones there were in the foot and then how many ligaments there were. And the fact that Susie could remember the names of all the bones and the ligaments, and then all the things they did, I was just like “That is cool, but like nerd cool”. And, unashamedly, I’m a nerd,’ Jeremy says.

As a young dancer, Jeremy felt a step behind other male dancers who had started learning the discipline 10 years ahead of him.

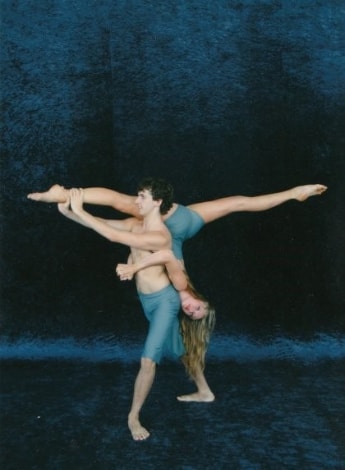

The complexities of the human body would continue to fascinate Jeremy long after he reached the point in his life when he realised he was not destined to be a professional dancer. Having been introduced to dance by a fellow Year 9 student Lewis Major, now a prominent choreographer in South Australia, Jeremy arrived late to the discipline— a good 10 years behind many of the other dancers he would train with. Although he displayed a natural talent and was hyper mobile, Jeremy struggled with the pirouettes required of professional male ballet dancers. ‘Because my legs were quite hyper extended and I had quite arched feet, I found it really hard to find my centre of gravity in a pirouette position,’

Jeremy says. ‘And because all the other kids that I was dancing with had 10-plus years more on me, they were doing triple, quadruple pirouettes. The boys were doing eight to 10 pirouettes and I was still trying to figure out where I was on my legs, so that was always a big struggle for me. I reckon if I could have done clean triples there’s a possibility that I might still be dancing, because boys have to pirouette, that’s the thing.’

Coming to the conclusion that he would not be a professional dancer, Jeremy began to very carefully plot a new course for his future. While he continued to love the art form, and still does to this day, Jeremy realised he wasn’t a fan of the dancer’s lifestyle. ‘It is a hard slog being a dancer. What you see on stage is the tiny, tiny tip of the iceberg. It’s the gruelling days, the rehearsals that go on forever, and the instability in the dancer’s life … that’s one of the reasons why I gave up.

When I did make the decision to give it up, I gave it up cold turkey because I knew that it had been my life for so long that I needed to put a big wedge between it and my life,’ he says.

Determined to put his dance knowledge to good use though, Jeremy packed his bags and left New Zealand, returning to Adelaide with a mission to become a dance physiotherapist. He enrolled to do his Polestar Pilates training and quickly met physiotherapist Jenni Guest, APAM, who he credits with becoming his mentor, his first physiotherapist employer, a colleague and a close friend. ‘I owe much of my career to the nurturing, guidance and support of Jenni Guest,’ Jeremy says of their connection.

Jeremy completed his undergraduate degree in human movement, and then undertook a Master of Physiotherapy at the University of South Australia—all the time using Pilates to pay his tuition. Jeremy became a mentor and educator for Polestar Pilates Australia by the end of his master’s program, and he now teaches and instructs the Certificate IV and diploma-level students. At the end of his university degree, Jeremy started working at Smart Health Training and Services in Adelaide, where he honed his skills as a dance physiotherapist under the watchful eyes of Jenni Guest, as well as ensuring he managed his standard musculoskeletal client list.

Drawn by the appeal of the big city life, Jeremy moved to Sydney in 2016 and began working and managing Polestar Pilates Studio while also maintaining a 30-hour a week clinical load on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. For two gruelling years Jeremy battled the daily Sydney traffic, hitting the road at 5.15 am to commute from his home in Darlington to start work at 8.00 am. “I’d committed to working at a place in Brookvale. I didn’t realise, because I’m a little country boy from Adelaide, when I looked on the map of Sydney I’m like “Oh yeah, it looks close on the map, there’s like one, two bridges on the road, that’ll be cool”. How naive was I?’

Eventually Jeremy began seeking other work opportunities, and while teaching the Certificate IV course he had a fortuitous meeting with one of his students, Tamara Salkavich, APAM, the head physiotherapist for the Indigenous Australian contemporary dance company, Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Bangarra Dance Theatre dancers, pictured here in the production called Dark Emu, present a unique set of challenges to the physiotherapists who treat them. Photo: © Daniel Boud.

‘Tam came and did the course and then I mentored her through some of her course because she missed one of the course weekends for some reason. So we had to make up some material and Tam and I just really clicked quite quickly,’ Jeremy said. ‘She kept saying “do you want to come and work with Bangarra, do you want to come and do some stuff? There’s an opening.” And I was like “Oh love to, but I just can’t fit it in, because I need to be driving for like 16 hours of my week!”

Jeremy quit the Northern Beaches and quit Australia to travel around India for a month before returning home to Sydney. In his first week back, Tamara serendipitously called Jeremy and asked him, once again, to come and work with Bangarra—and he’s been with the dance troupe ever since. Jeremy now splits his time between his clinical work at Square One Physiotherapy and Sports Injury Management in Mosman and with the dancers at Bangarra, where he is part of a treating team which includes another physiotherapist, five Pilates instructors, massage therapists and two sports doctors, Dr Grace Bryant and Dr James Lawrence. It takes a lot of work to keep the dancers in performance- ready shape, something Jeremy knows all too well.

‘I speak their dance language, their vocabulary, so when they talk about things in their contemporary class, like the barrel turn, if they’re talking in their ballet class about their developpe [a movement in which one leg is raised and then kept in a fully extended position] I don’t have to go “Oh what’s that? Can you show me?” because I’m a dance boy and I’m a physio,’ Jeremy says.. ‘Having a dance background helps me understand the culture and the demands that are placed on the dancers—not only the physical demands of having to do the quite difficult movements, but also the emotional investment they’ve put into it as well.

‘I’m not only looking at them to see what their feet are doing, I’m also asking how they are sleeping, how are they going with the choreography, how is their relationship with the choreographer or with the artistic staff. It’s so multifaceted when you treat a dancer. And the dancers’ bodies are so interesting,’ he says. ‘For example, for a few days the dancers were having to hold sticks up in the air while the choreographer was deciding who holds the stick where or whatever, or the time there was a canoe that the boys had to have on their shoulders. So they all came in that week with upper cervical and shoulder and thoracic presentations that would take a normal patient that I’d see in the clinic probably three to five weeks to get over.

‘Those dancers are back the next week with a totally different complaint like lower back pain or something because the choreographer is working on something down low or on the floor and they’ve been rolling around. So they’re all coming in with their lower backs and their hips a little bit achy, and I ask them how their shoulders are and they’re like “the shoulders and neck are fine now, it’s the lower back or the hips that are needing some work”.

‘We give the dancers lots of hands-on treatment because their bodies need it. We try and jump on the niggles as quickly as we can before it becomes an injury, because an injury means time lost. Time lost to a dancer is money to the company and emotional distress. It’s huge for the dancer. It’s really heartbreaking to tell a dancer that they need to have four weeks off. That’s like the end of their world if you say that to them, because it’s their life, it’s what they do, and it’s how they make money,’ Jeremy says.

When the dancers are in town, Jeremy shares the workload with Tamara. In a three-hour shift they work in half-hour blocks, treating up to six dancers in that time. If more dancers need treatment, shifts are extended to cater for their needs. ‘I think the longest I ever stayed for was about five hours on one day, so that’s 10 dancers, bang, bang, bang, bang, in a row. Yep, my poor little hands.’

Jeremy says he thrives in an environment where he can blend his physiotherapy, dance and his Pilates rehabilitation skills. He is also volunteering his time on the Pilates Alliance of Australasia Board as the treasurer for the past three years and works to help lift the level of skill of Pilates instructors in Australia to better enable them to work with allied health practitioners.

‘So what drives me to make a difference in physiotherapy? I know how hard the life of a dancer is, I know how hard they work, I know how much time and emotion they invest into this, and how much their families have invested into them as well,’ he says. ‘I just want to make the dancers’ lives as easy as possible. So in my capacity as a physiotherapist I help them with their pain and I decatastrophise things and enable them to keep dancing optimally and pain-free for as long as they can.’

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.