Implementing psychosocially informed practice for treating chronic pain

There is a push for for the development of psychosocially informed practice skills in physiotherapists for optimal outcomes for people with chronic pain.

Chronic pain is the leading cause of disability and disease burden globally (Mills et al 2109).

In Australia, 20 per cent of people over 45 years have chronic pain, leading to increased activity limitation, care seeking, opioid use and hospitalisation (AIHW 2020).

The traditional biomedical model of treating chronic pain was initially challenged over 40 years ago (Engel 1997, Waddell 1987), yet continues to be a common treatment approach despite limited evidence of effectiveness and the potential for significant harms (Foster et al 2018).

A biopsychosocial model reflecting biological (including pathoanatomical, impairment and neuroimmune factors), psychosocial and social factors (Hodges 2019, Hodges et al 2019) is now accepted as a more effective approach for health practitioners treating chronic pain, and is recommended in most clinical guidelines (Oliveira 2018).

Within the context of the biopsychosocial model, psychological factors can be seen as driven by cognitions (meaning thoughts) based on previous experience (Nicholas et al 2011).

These cognitions make sense of incoming signals representing noxious stimuli (Turk & Melzack 2010, Fordyce 1975, Linton 2005) and help to shape the pain experience (Linton & Shaw 2011).

Despite methodological shortcomings in the literature (van Oort et al 2012, Hilfiker et al 2007, Ashworth et al 2011), psychosocial factors have been shown to predict outcomes of people with pain (Ramond et al 2011, Gray et al 2011, Iles et al 2008, Hartvigsen et al 2004).

There is significant evidence supporting the relevance of specific psychological factors in the individualised treatment of chronic pain, including:

- self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task; Jackson et al 2014, Alhowimel et al 2018)

- catastrophising (an exaggerated negative cognitive-affective orientation towards pain; Alhowimel et al 2018, Schutze et al 2018)

- specific beliefs such as recovery expectations (Alhowimel et al 2018, Hayden et al 2019, Green et al 2018, Hruschak & Cochran 2018, Martinez-Calderon et al 2019, Leeuw et al 2007)

- anger (Sommer et al 2019) and

- mood including depression and anxiety (Nicholas et al 2011, Hruschak & Cochran 2018, Pinheiro et al 2016, Power et al 2001).

Social factors including socioeconomic status, income/education level, perceived lack of support, work-related factors and family issues are also likely to be relevant to the treatment of pain (Nicholas et al 2011, Linton & Shaw 2011, Mayer et al 1985, Shmagel et al 2016, Pincus et al 2010).

There are different modes of treating chronic pain using a biopsychosocial approach. Multidisciplinary pain management focusing on goal-oriented graded activity and exercise has demonstrated long-term effectiveness (Kamper et al 2015).

However, such treatment is intensive, costly and may be difficult to access. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) provided by psychologists also have evidence of effectiveness (Ehde et al 2014, Hilton et al 2017, Hughes et al 2017, Simpson et al 2017) but generally don’t incorporate exercise, which also has demonstrated modest effects on chronic pain (Geneen et al 2017).

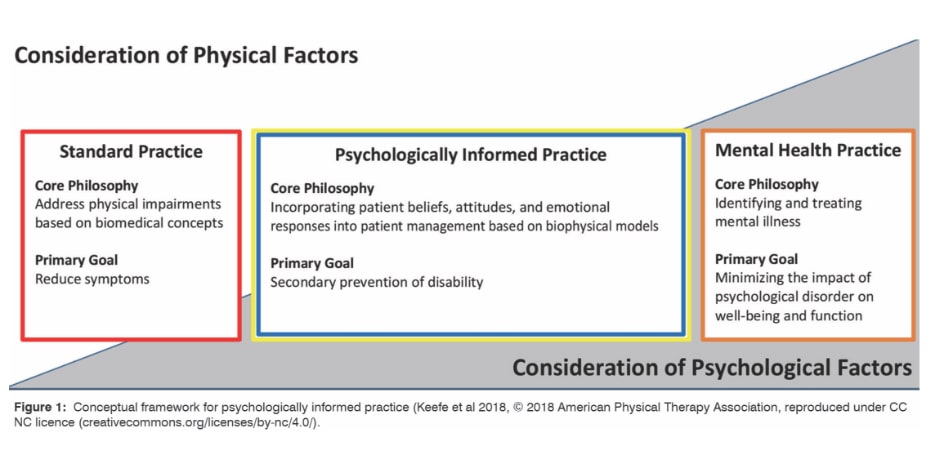

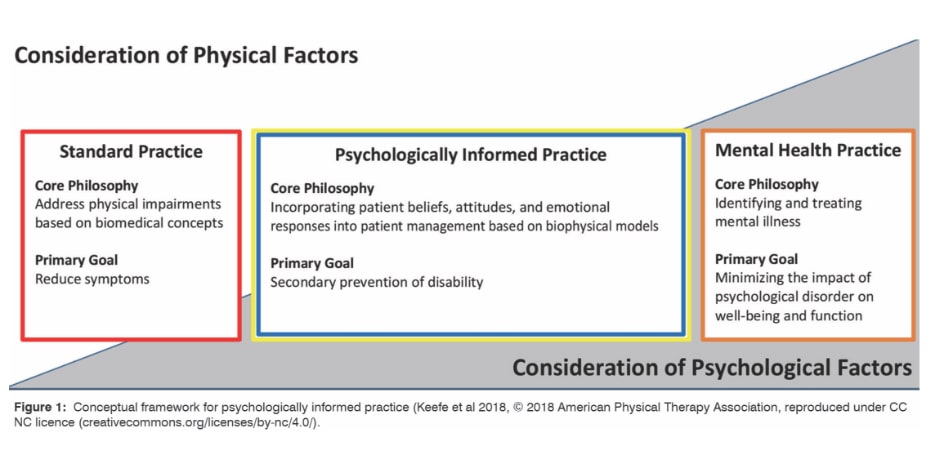

Physiotherapy utilising ‘psychosocially informed practice’ (PIP; Keefe et al 2018; see Figure 1, main image) is potentially comparable with multidisciplinary pain management, CBT and ACT, has some evidence of effectiveness (Richards et al 2013, Schaafsma et al 2011, Bostick 2017, Silva Guerrero et al 2018), and may be a more feasible option for the large number of people with chronic pain worldwide.

Most physiotherapists are aware of the importance of considering psychosocial factors in the management of chronic pain (Hill et al 2020, Synnott et al 2015, Alexanders et al 2015), although this is sometimes attached to the perception of patients being demanding, attention seeking and under-motivated (Synnott et al 2015).

Psychosocial screening is a simple and time-efficient process allowing identification of people at risk of poor outcome and is an initial step in facilitating PIP or referral for more specialised treatment.

However, more than 60 per cent of physiotherapists in New Zealand don’t use screening tools such as Örebro Musculoskeletal Screening Questionnaire (Hill et al 2020) despite significant limitations in physiotherapists’ capacity to identify relevant psychosocial factors for the treatment of chronic pain (Beales et al 2016, Miki et al 2020).

Recent data suggest that despite awareness of PIP principles, physiotherapists prefer dealing with pathoanatomical or impairment- based components of chronic pain (Synnott et al 2015, Fritz et al 2019).

This preference may be influenced by the perceived inadequacies of undergraduate and postgraduate training on PIP skill development (Synnott et al 2015, Fritz et al 2019).

Training issues may also be a factor contributing to the low levels of confidence in applying PIP by physiotherapists (Alexanders et al 2015, Fritz et al 2019, Driver et al 2019, Zangoni & Thomson 2017, Cowell et al 2018, Forbes et al 2018, Holopainen et al 2020, Driver et al 2017, Karstens et al 2018).

These factors potentially combine with financial disincentives, time limitations and insufficient support from managers/peers, particularly within the private practice setting (Synnott et al 2015, Fritz et al 2019, Karstens et al 2018), resulting in a relatively low uptake of PIP by physiotherapists for people with chronic pain apart from goal setting as a commonly used strategy (Alexanders et al 2015, Driver et al 2019).

It would appear that improved training for physiotherapists and PIP is required.

However, research on the effectiveness of training for psychosocially informed interventions is generally of poor methodological quality and there is insufficient data on identifying the most effective approach (Keefe et al 2018, Herschell et al 2010).

Physiotherapists have a preference for combinations of didactic and interactive training methods (Driver et al 2020) despite the fact that this may not result in sustained practitioner behaviour change in clinical practice (Holopainen et al 2020).

Intensive training in PIP may improve confidence and capacity to perform PIP (Synnott et al 2016); however, outcomes in high-quality clinical trials for physiotherapists having undergone such training (O’Keeffe et al 2019, Hill et al 2011) are of questionable clinical importance.

It has been suggested that practitioner PIP skills and patient outcomes would be improved by training more specifically individualised to practitioner capabilities and characteristics (Holopainen et al 2020), but this proposal has not been evaluated.

Treatment fidelity can be defined as methodological strategies used to monitor and enhance the reliability and validity of interventions and has been explored extensively in psychosocially informed treatments (O’Shea et al 2016).

Some key components of evaluating treatment fidelity have potential relevance to the evaluation of training programs of PIP skills in physiotherapy (O’Shea et al 2016, Karas & Plankis 2016, Borrelli 2011), including processes to:

- ensure adequate development and description of the treatment (eg, theoretical constructs underpinning the treatment are described and internally consistent, treatment dosage and content are described in written materials)

- ensure providers have been satisfactorily trained before commencing practice (meeting minimum competency standards on assessment) to deliver the treatment (eg, sufficiently experienced trainers, training program parameters, individualised training, optimising practitioner ‘buy in’, determining practitioner eligibility/qualifications to provide treatment)

- monitor and improve delivery of the treatment (once treatment provision has commenced) so that it is delivered as intended (eg, ensure skill maintenance/improvement over time, evaluation of dose/content of treatment delivered, consideration of non-specific treatment effects, engagement with written materials and other treatment fidelity methods, collaborative rather than hierarchical monitoring, remedial training for practitioners who don’t meet minimum competency standards)

- monitor and improve the ability of patients to understand and perform treatment-related behavioural skills and cognitive strategies during treatment delivery (eg, questionnaires on patient adherence and understanding of key concepts, assessment of change in activity/exercise, evaluation of psychosocial outcomes)

- consider relevant methods of pre-post assessment including written, audio/video review of patient consultations, practitioner/ patient self-report or questionnaire and independent evaluation of practitioner competency.

The training of PIP skills for physiotherapists viewed in the context of the treatment fidelity literature support the statement that ‘Essentially, there does not seem to be a substitute for expert consultation, supervision, and feedback for improving skills and increasing adoption’ (Herschell et al 2010).

In this context it seems unlikely that short course training or postgraduate degrees consisting of predominantly online training will result in consistently acceptable levels of PIP for physiotherapists.

The Australian College of Physiotherapists has established the Pain Specialist pathway to fellowship, incorporating a rigorous training program to develop specialist-level PIP skills including communication, assessment, understanding of and treatment for the range of psychosocial factors relevant for chronic pain.

Physiotherapists progress to the Pain Specialist program through Pain Titling.

Given the complexity and challenges described, it is arguable that these career pathways represent an effective methodology for developing PIP skills in physiotherapists that lead to optimal outcomes for people with chronic pain.

Email inmotion@australian.physio for references.

>>Dr Jon Ford (PhD), MACP, is a pain registrar undertaking Fellowship of the Australian College of Physiotherapists by Clinical Specialisation. He is Adjunct Associate Professor of Physiotherapy at La Trobe University; and Clinical and Managing Director of Advance Healthcare, a network of practices providing multidisciplinary pain management services to the community.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.