Knowledge helps to ease the pain

The Australian Pain Society’s 42nd Annual Scientific Meeting in Hobart in April celebrated the Global Year for Translating Pain Knowledge to Practice. InMotion catches up with some of the country’s leading speakers and presenters at the conference’s topical sessions, workshops and plenary and concurrent sessions.

Taking the pain out of online learning

APA Pain Physiotherapist Dr Tania Gardner MACP is a senior physiotherapist in the Department of Pain Medicine, St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney. Tania, whose research interests lie in chronic pain, patient motivation, goal setting, therapeutic alliance and rural/regional access to chronic pain management, speaks here about her presentation.

Working with the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, Dr Tania Gardner has led the team to develop the first multidisciplinary online chronic pain management program, Reboot Online.

The program sits on the This Way Up platform alongside a suite of online programs for various mental health conditions.

Information learned through the program was shared with those attending a topical session at the recent Australian Pain Society’s annual conference that explored digital health interventions for pain management.

At that topical session, Tania told attendees that her focus was on patient engagement in digital health and chronic pain and explained how that engagement could be used to improve adherence to the This Way Up online chronic pain management program.

‘While developing the program, we involved consumers to help inform what we do.

'Most recently we used the qualitative feedback to improve the program by changing components of it to make it more interactive and diverse and we also included some multimodal audiovisual components in the program,’ Tania says.

‘In terms of consumer engagement and digital health, you need to have a large team to do it because it is complex.

'It’s not just about the content. It’s how you present and deliver that content.

'Things like health literacy need to be considered, so the program needs to be at a level that the majority of the population can understand.

'Reading isn’t for everyone; you need to consider diverse delivery of the content.

'We’ve got audio, animation, text [and other] modes of delivery in our program to accommodate this.

‘We found that patients from rural and regional areas were more adherent to the program, as they have limited choice in terms of the local clinical services, so that was a factor.

'Interestingly, patients with high kinesiophobia or fear of movement had a lower adherence to the program.

'That probably suggests that these patients need to have more clinical interaction before participating in the online program.’

Tania says that developing and refining the program involved incorporating considerable consumer feedback and adaptations were made to match consumer needs and wants.

Getting the program out to clinicians and patients also takes a team, she says, as does training clinicians to help their patients get the most out of the program.

At the topical session, Tania told the audience that a recent paper published about the impacts of COVID-19 on the chronic pain online program showed there had been a 287 per cent increase in uptake during the pandemic with similar effectiveness.

‘It showed that you can increase accessibility without losing the effectiveness of the program, which was nice to know,’ Tania says.

‘Accessibility to multidisciplinary chronic pain management in general is really limited. This program gives that access to patients and it can be used in different models.

‘Clinicians can use it alongside their own treatment in a clinic or a physio could have the patient do the online program at home and come into the clinic [so the physio can check] their understanding of the lesson content and their skills and revise exercises, for example.

'Clinicians could also set up a computer in their clinic for patients who don’t have the internet.

'They can come in, do the online program and then work with the physio.

'Clinicians can adapt the model to their own circumstances and can think of ways to optimise the staff and space resources to increase patients’ access to evidence-based, multidisciplinary pain management.’

At the conference, Tania also spoke about her recent randomised controlled trial looking at using telephone coaching to improve adherence to the chronic pain management online program.

She found that using telephone coaching alongside the online program helped with onboarding of patients, so that more patients got started and completed the program.

Participants in the trial received one phone call every two weeks, with a total of eight fortnightly phone calls over three months.

Once the online program is completed, patients can continue to access it for a further 12 months and are also able to download a suite of video resources that are included in the program, Tania says.

Back to basics on pain and movement

Kevin Wernli APAM is a physiotherapist and researcher with a passion for using technology to enhance access to equitable and effective care. Kevin, who works clinically in a digital health startup and supervises and lectures at Curtin University in Perth, talks about the paper he presented at the conference.

Less was more when it came to the findings of the paper ‘Movement, posture and low back pain. How do they relate?’, as discussed at the Australian Pain Society’s annual scientific conference by lead author Dr Kevin Wernli.

The paper details how Kevin and his team used a replicated single-case design to gain in-depth insights into 12 participants in a way that studies with much higher numbers of participants can’t.

‘There’s quite a wide belief among physios, and generally in the public, that movement and posture are important for low back pain.

'Specifically, when people have low back pain we need to change their movement and posture in some way in order for them to get better.

'So, there’s this idea that there is a relationship between movement and posture changing and pain or function improving,’ Kevin says.

‘But when we look at the literature, that’s not very well supported.

'Most of the systematic reviews actually suggest that movement infrequently related to people improving.

'So, the question was whether the literature was looking at this question correctly or whether there was, in fact, no relationship.

'When we did a bit of a deeper dive, we identified that the way most of the systematic reviews and studies looked at this relationship was very generic.

‘They might look at the same movement for everyone; it might be a forward-bending range of motion, for example.

'But some people don’t have pain bending; some people have pain sitting, standing, running, lifting or twisting.

'The assessment is not really tailored to that individual person.

‘Then, when you look at it from a group average perspective, and you look at an average measure of movement and pain for everyone before a treatment, and then another group average at the end of treatment, you lack that individuality—some people might have changed heaps, some very little, but it can all get washed out with averages,’ Kevin says.

‘And the same people who improved in movement might not be the same people who improved or changed in their pain or function.

'There are limitations to the way the studies are done; they’re not individualising patients or specific individual problems.’

This set Kevin and his team on a journey to investigate using fewer participants in a deeper way.

Instead of investigating a lot of people and looking at averages (and only looking at them before and after), the team flipped that design to use far fewer participants, but look at them in detail by doing repeated measures over time.

‘We asked them at the start what the key activities or functions they have problems with were and then we measured them on repeated occasions—up to 20 times over a 22-week period.

'Almost weekly for six months I was catching up with these people and putting movement sensors on their backs, measuring their movement and posture.

'At the same time they were completing online questionaries about their pain and their function as well as a whole bunch of different psychological factors.’

Kevin, who was awarded a Physiotherapy Research Foundation project grant in 2017 for his project ‘Does changing movement matter? Understanding the relationship between changes in movement, pain, activity limitation and psychological factors in persistent low back pain’, told the conference that the results of the study of the 12 participants showed just how variable people are in their experiences.

And that movement and posture appeared to be important in treating low back pain.

‘One of the challenges with the amount of measures we took was identifying one variable to try to relate to pain and function improving.

'We ended up with a bunch of different ones for each person and then ran statistics on each of those to identify how strong the relationships were for different people.

'The biggest surprise to me was just how variable people are—sometimes they had really strong relationships with the speed of bending or with the range of how far they bend.

'And sometimes it was more to do with their muscle tension and sometimes it wasn’t.

‘Another interesting finding, in my opinion, is that people could get better even when measures that we thought were important didn’t actually change.

'That speaks to the idea of a “whole-person journey”.

'It’s not just to do with movement or posture and not just to do with one single factor.

'It’s also to do with the way they’re thinking and feeling and with other things going on in their lives from a stress perspective.

'It’s a lot more complicated than we first thought, which is true of lots of research.’

Having spoken about this topic on many occasions, Kevin says that the feedback he gets from physiotherapists and other health professionals is that they intuitively understood that movement and posture were important in treating low back pain but had been unable to find support for that in the literature.

‘When all these studies come out and say “Movement is not important; movement’s not related; it’s not related at a group level”, clinicians often feel a bit deflated.

'They say, “I see these patients and I can see that when their movement changes, they improve”,’ Kevin says.

‘The traditional narratives for low back pain are, “You’ve got to sit up tall”, “You’ve got to brace your core” and “You’ve got to keep your back straight”.

'We know from the literature that people with back pain usually demonstrate these protective patterns more than people without back pain.

‘What we highlighted as part of this study (and it’s obviously small numbers and early days; further research is needed)... is that as people get better, when it’s related to their movement changing, 93 per cent of the time their movement or posture is becoming ‘less protective’.

'So, they’re relaxing when they’re moving, they’re slouching more, they’re bending more, they’re rounding their back more, they’re moving faster.

'It speaks to this idea that the protective response in their movement or postural system might be an over-protective response.’

Taking control of pain management

Hayley Leake is a physiotherapist and PhD candidate at the University of South Australia. Hayley’s research focuses on understanding the mechanisms of, and optimising interventions for, chronic pain in adulthood and adolescence, with a particular focus on pain science education. She provides a synopsis of a workshop on formulating self-management strategies for persistent pain conditions.

The role of education in self-management for persistent pain

Alongside developing skills to independently manage pain, modern definitions of self-management emphasise the importance of understanding that support is available to access when needed (Kongsted et al 2021).

Those supports and skills include physical, psychological and pharmacological therapies. Yet often, self-management strategies conflict with pre-existing beliefs about pain.

Adults with chronic pain describe believing that their back is vulnerable, damaged and easily injured, leading them to protect it (Darlow et al 2015) by avoiding painful activities (Bunzli et al 2015).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, education is recommended as a component of self-management in guidelines for chronic pain (eg, the NICE guidelines for chronic LBP (Bernstein et al 2017)).

Education has been described as the missing link to turn advice to stay active, exercise and seek psychological therapy into sensible strategies to self-manage pain (Moseley 2019).

Pain science education seeks to provide an explanation of what pain is, what function it serves and what biological processes are thought to underpin it (Moseley & Butler 2015), neatly summarised as the ‘what, why, and how of pain’ (Pate et al 2019).

Pain science education has typically been developed in a ‘top-down’ fashion, seeking the advice of experts (eg, clinician and researcher consensus (Leake et al 2019)), yet interventions developed in this way can lack personal relevance (Robinson et al 2016).

By placing consumers at the centre of research, a ‘bottom-up’ approach can be used to refine education interventions.

In the workshop at the conference, we explored studies that identified consumers’ views about how pain works, or how we teach people about pain.

Exploring existing concepts of pain

First, to accompany the existing literature for how older adults conceptualise pain, we presented the findings from a qualitative study exploring how young adults conceptualise the biology of pain.

Importantly, those young adults had been experiencing chronic pain since childhood (average duration 11.4 years) and in that time they had been exposed to a variety of interventions for pain.

An interesting finding was the theme that pain represents an unhealed body.

This mindset goes against the normative view that ‘young bodies heal quickly’ and presents an opportunity to include education on an alternative mindset about a young adult’s body: that it is capable of healing.

Two other themes pointed to body systems, describing that pain is related to faulty messaging (a problem in the nervous system) or stress (a problem in the endocrine system).

Shifting focus from something being wrong in the tissues to a broader understanding involving other bodily systems may be a somewhat adaptive way to understand the function of pain.

Are certain learning objectives more important than others?

Next, we presented the findings of a decade-long audit process that led to the identification of key learning objectives for pain science education.

This process included consumer participation via consultation.

In the 12–18 months after consumers received treatment for chronic pain that included pain science education, they completed a survey identifying which concepts where helpful and why.

Learning objectives compiled from three cohorts of consumers (n=278) have been used to inform fact sheets for public education about pain (freely available here).

In an effort to understand why certain learning objectives are deemed valuable, we conducted a mixed method study (Leake et al 2021).

In that study, we asked adults who had received a pain science education intervention what, if anything, they had learnt that they believed was important for their improvement with persistent pain.

They said that the value of learning that ‘pain does not indicate tissue or bodily damage’ lay in a reduction in the fear of injury and a justification to stop avoiding (painful) movements.

They also said that framing pain as ‘an over-protective response that could be lessened’ was an important concept because it provided hope that their pain condition could change.

The success of educational interventions could further be improved by research designs that partner with consumers in the design of resources.

There are potentially important benefits to methods such as co-design (efforts are underway; watch this space) and a focus on ensuring that language is aligned appropriately.

Up, up and away with pain

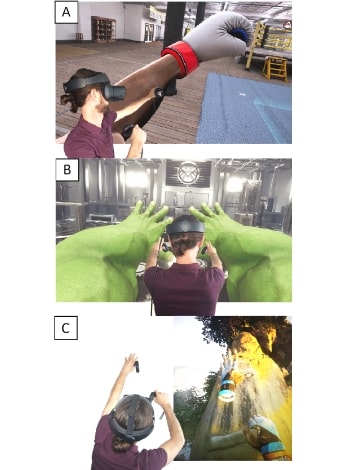

APA Pain Physiotherapist Dr Daniel Harvie MACP is a lecturer and pain scientist at the University of South Australia. Daniel’s research focuses on leading-edge theories of body perception and how they might inform new approaches to chronic pain, often involving VR and sensory training. He is the co-author, with Lorimer Moseley, of the new book Pain and Perception: A closer look at why we hurt.

Do your clients ever say that they feel like they are falling to pieces?

Like their bodies are failing them?

This, in my estimation, is a common experience for people in pain.

It seems to reflect something of a loss of trust in one’s body, a deficiency in physical self-confidence or an increased sense of physical vulnerability.

But what if we could help a client swap their body for that of a superhero?

Would they still feel vulnerable then?

And would it change their pain?

Well, thanks to virtual reality (VR) we now have a way to do this.

Sort of.

VR enables us to replace the physical world with a digital one.

It also allows us to replace our real bodies with simulated bodies (also called avatars).

Importantly, an avatar can be overlaid exactly where your real body is and it can be synchronised to your real motion.

Two illusions result:

- the place illusion—the sense of presence in a virtual world

- the embodiment illusion—the sense that the virtual body is your body.

Without getting too neurosciency (or perhaps I will), these illusions seem to be possible because of the way perception works (Harvie & Moseley 2021).

That is, our perception of our bodies and our environment is dependent on brain-held maps of the same.

These brain-held maps are continuously updated in response to new sensory and non-sensory data, subsequently altering our perceptions and cognitions.

Some groundbreaking findings have shown that profound psychological, cognitive and physical effects can arise from swapping one’s real body for a digital avatar (eg, see Nishigami et al 2019 and the review of the ‘Proteus effect’ in Slater 2017) and we were inspired to take the idea further.

We were delighted to share this early work at this year’s Australian Pain Society conference alongside Sylvia Gustin from Neuroscience Research Australia and her VR walking simulator research in people with spinal-cord-injury-related pain.

Our work to date centres on:

- a single-case report, which lays out the idea in the form of a multi-session intervention (Harvie et al 2020)

- a single-session randomised controlled trial that looked at the immediate effects of superhero embodiment as distinct from general virtual reality immersion (papers in review).

In the single-case report, we developed this embodiment idea into something we called virtual reality body image training.

Virtual reality body image training involves embodying superhero and athlete-like avatars, while acting out their characters.

Upon embodying these avatars, the participant with severe and persistent low back pain felt an immediate boost in confidence to move, with corresponding reductions in pain.

After multiple sessions and a period of in-home training, these changes appeared to stick.

Of course, we can’t draw conclusions from a single case, but it certainly got our attention.

Our next study sought to ask if the immediate effects seen in this single case might be experienced more generally by others in pain.

To answer this, we teamed up with The Hopkins Centre and the staff at the Princess Alexandra Hospital persistent pain management service.

The study involved 30 people with severe and debilitating low back pain.

Online games such as (A) Creed: Rise to Glory, (B) Marvel Powers United and (C) The Climb can be powerful tools to help patients manage their pain. Image: Daniel Harvie.

What we found was that yes, in general people did experience a boost in ratings related to physical confidence and bodily trust while embodying these superhuman avatars.

However, this immediate boost was on average about 40 per cent whereas it was about 60 per cent in the single-case report.

The boost did not occur in the generic VR control group, suggesting that the embodiment is responsible for the effects observed.

While we did not detect an immediate improvement in pain, we were encouraged that there was no exacerbation in pain.

This group showed high levels of pain and irritability and given that the intervention involved movement, one might have expected pain to increase.

So while it would have been nice to see pain reduction, this was nonetheless an important finding.

No effects from the single-session intervention remained at the one-week follow-up, which was consistent with the single-case report—where sustained benefits were only noted after several weeks of intervention.

So where from here?

It is, of course, premature for us all to run out and buy VR headsets.

But it is not premature to think about how we can help our clients rebuild trust in their bodies (you might do this already).

The best place to start would be re-engaging clients with bodily experiences that impart a sense of ‘I can’, that counter perceptions of vulnerability and that bolster a sense of physical confidence.

Imparting key concepts (Leake 2021)—for example, that pain and damage are poorly related and that our bodies and our pain systems are adaptable—will likely be helpful here too.

Seeing all sides of interdisciplinary care

APA Pain Physiotherapist Megan Willing works at the Persistent Pain Service, Royal Hobart Hospital, and is the coordinator of the service’s Pain ECHO program, which offers practical pain education for health clinicians through patient case discussion. Megan summarises the physiotherapy pre-conference workshop, of which she was a co-presenter.

At the Australian Pain Society’s Annual Scientific Meeting, the topic of the physiotherapy pre-conference workshop was ‘Interdisciplinary pain management—what it is and how do you do it (really)?’

The aim was to discuss interdisciplinary care and to encourage self-reflection and possibly action in our own practice of interdisciplinary care.

Fittingly, the presenting team was interdisciplinary: Tim Austin (a Specialist Pain Physiotherapist (as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2021), convenor and our source of inspiration), myself (an APA Pain Physiotherapist), psychologist Bernadette Smith and general practitioner Frank Meumann.

Both Bernie and Frank have extensive experience in pain management.

The amazing Anne Daly (a Specialist Pain Physiotherapist (as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2021)) contributed enormously to the design but was unable to attend.

I’ve worked in pain services and in private practice.

I deeply value interdisciplinary care. It is recommended as the ‘ideal approach’; however, I also know it can be difficult.

I have seen how the different health disciplines have different cultures, languages and assumptions.

These add richness to interdisciplinary care and are also potential sources of misunderstanding.

Interdisciplinary care is more challenging when team members are dispersed and unfamiliar to each other.

More than 20 people attended the workshop.

The majority were physiotherapists; however, there were others including psychologists, exercise physiologists, nurses and medical pain specialists.

Most were involved in interdisciplinary care, so there was a lot of experience to share.

The workshop participants shared their experiences on the ‘good’ and the ‘bad/difficult’ aspects of interdisciplinary care.

The ‘good’ whiteboard filled up the fastest.

Despite all the difficulties people raised, the benefits of interdisciplinary care were at the forefront of participants’ minds.

One major challenge that was raised was time, specifically the lack of time and difficulties in finding mutual time for conversations (letters are good, but have limitations).

Other challenges included funding, not having the required health practitioners in your region, ensuring that the person with pain is the central team member and discipline-specific jargon.

The importance of communication (written, over the phone and/or via meetings) was emphasised—regular, considerate of the perspectives of the other professions and working to stay on the same page.

Building relationships with other practitioners over time was also discussed.

Tim then interviewed Frank and Bernie about their experiences.

Bernie reflected that a key feature was the patient’s sense of helplessness, hopelessness and failure (theirs and that of health professionals), with a resultant need to build trust.

She and her patients discuss what information they are comfortable with her sharing with other professionals; this may include the patient’s fears and beliefs, a trauma history and how to respect that and mental health issues affecting pain and/or management.

Bernie explained that she relies on a physiotherapist’s input to fully understand the patient’s situation (eg, is it safe to be more active; what is the prognosis of the ‘bio’ condition?).

She finds that physiotherapists can underestimate their importance in patient care (particularly if not hands-on) and can have high expectations of themselves, of their treatment and of patients in chronic pain.

Bernie flagged that physiotherapy acronyms can be challenging and that psychologists often have limited anatomical knowledge.

She emphasised truly patient-centred care as the driver for the patient to contemplate change and that it is important to listen and understand before leaping to ‘theories’ and action.

Frank discussed the long-term relationship he has with his patients, often extending to their families.

This awareness of a person’s history can be very useful in treating persistent pain.

GPs are usually managing multiple health conditions in the one person and pain management is not always at the forefront.

He reflected that GPs have less training in musculoskeletal assessment and that he finds it useful if the ramifications of physiotherapy assessment findings and the goals of treatment are explicitly communicated to him (eg, not just ‘hip extension limited to X’ but how this affects the patient’s gait and how ‘glute exercises’ will help).

We finished with an ‘interdisciplinary team meeting’ role-play.

Participants were divided into ‘physiotherapist’ (the non-physio participants), ‘psychologist’ and ‘GP’.

They discussed a patient case and considered what their health professional needed from—and had to offer—the other team members.

There was an initial profound silence… then the conversation grew.

An intrepid few acted out the ‘team meeting’.

Afterwards, participants told us that putting themselves in the shoes of other professionals was really challenging and useful.

This simulated team meeting was my favourite section—it seems so important to appreciate what each profession needs from physiotherapists and what they have to offer us.

We have so much to learn from each other.

Managing postoperative pain

APA Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapist Dr Ianthe Boden is a senior lecturer at the School of Health Sciences, University of Tasmania, and Clinical Lead Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapist at the Launceston General Hospital. Ianthe is currently leading a consortium of 35 hospitals across six countries to assess the incidence of pulmonary complications and associated outcomes after major surgery. Speaking at the Acute Pain workshop, Ianthe discussed epidural analgesia after major abdominal surgery.

Compared to patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), epidural analgesia is associated with less pain after major abdominal surgery, yet higher failure rates and more adverse events such as pruritus and severe hypotension (Salicath 2018).

Despite this, epidural use is encouraged within enhanced recovery after surgery pathways (Gustafsson 2019).

Consequently, epidurals are increasingly being used to manage pain after major abdominal surgery.

An understanding of the different analgesia modes and their impact on physical and respiratory recovery after surgery would be helpful for physiotherapists working in this space.

Unfortunately, there is little data on the relationship between analgesia and time to successful early ambulation, day of discharge from physiotherapy care, postoperative pulmonary complications (PPC), ileus incidence and hospital length of stay.

We conducted an individual patient-level meta-analysis of data from 1243 patients having major elective and emergency abdominal surgery at five hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

Data was aggregated from five clinical trials conducted from 2013 to 2019 (Boden 2021, Boden 2018, Boden 2018, Lockstone 2019).

Early ambulation was delivered with a standardised protocol, while ileus and PPCs were assessed using diagnostic screening tools.

Discharge from physiotherapy services was standardised using a threshold scoring tool (Brooks 2002).

Data was analysed with generalised linear regression models adjusted for surgical severity, acuity and existing comorbidities.

The aggregated population comprised patients having colorectal (45 per cent), upper gastrointestinal (19 per cent), hernia repairs and general surgery (17 per cent), renal (15 per cent), and gynaecological (2 per cent) and vascular surgery (2 per cent).

A third of the operations were emergency procedures.

Most patients were managed with multimodal analgesia: PCA and oral medications (71 per cent).

Oral analgesia alone was given to 18 per cent of the cohort.

Epidurals were initiated in 11 per cent of patients, with more than half of these patients then requiring a conversion to PCA (62 per cent).

Whereas 61 per cent of patients with a PCA were able to successfully ambulate with a physiotherapist away from the bedside for more than three minutes on the first postoperative day, only half of all patients (50 per cent) with an epidural could do so.

Time from the end of surgery to successfully ambulating with a physiotherapist was significantly later (p<0.001) in patients with an epidural (44 hours (SD 34)) or where an epidural was converted to a PCA (52 hours (SD 53)) compared to patients with a PCA (31 hours (SD 24)) or oral analgesia (35 hours (SD 30)).

In all groups the most common barrier to being able to participate in the first postoperative ambulation session was severe hypotension.

However, this occurred significantly more frequently in patients with an epidural (60 per cent) compared to those with a PCA (21 per cent, p<0.001).

Pain was a more frequent barrier to early ambulation in patients with a PCA (15 per cent) compared to epidural (4 per cent), yet this difference was not statistically significant.

Although early ambulation was achieved later in patients with an epidural, when adjusted for patient comorbidities and acuity, this did not translate into a greater number of days of the patient requiring physiotherapy (5 (2) days v 5 (3) days) or a statistically significant longer hospital stay (9 (5) days v 12 (11) days, p=0.67).

The PPC incidence was 18 per cent across the entire population.

The prolonged paralytic ileus rate was 26 per cent.

There was no association between analgesia mode and these complications.

This is the first large multicentre study to investigate the relationship between analgesia and physical recovery in the context of a standardised early ambulation program and data adjusted for patient acuity and comorbidities.

In this large cohort of abdominal surgery patients, one in 10 had their postoperative pain managed with an epidural.

There was a high failure rate, with more than half requiring a switch to PCA.

Despite severe hypotension significantly affecting the ability of patients with an epidural to mobilise on the first postoperative day, this appears not to affect longer term outcomes such as the amount of ongoing physiotherapy input required or hospital length of stay.

Whether a patient had an epidural or PCA did not affect their risk of a PPC or paralytic ileus.

This data provides physiotherapists with an improved understanding of the limitations to early ambulation after major abdominal surgery dependent on analgesia mode.

It provides confidence that although analgesia mode may have an impact on early ambulation on the first day after surgery, this is unlikely to affect the patient’s ongoing physical recovery, risk of PPC or time spent in hospital.

Message received about pain interventions

Professor Paul Glare FRACP, FFPMANZCA is Chair of Pain Medicine at the University of Sydney and Director of the Pain Management Research Institute. Paul, whose main research interests are cancer pain/cancer survivor pain and using digital technologies to support chronic patients to reduce their reliance on opioids, speaks with us about digital health interventions for pain management, which he explored at the conference.

It may not be the most sexy topic or garner the most headlines but SMS texting to help patients stay on track with their health goals and rehabilitation is big news in the healthcare profession.

And its use in pain management is still relatively new, says Dr Paul Glare, a physician who has interests in chronic pain therapies, pain management and palliative care.

In a forum at the Australian Pain Society’s scientific conference entitled ‘Digital health interventions for pain management’, Paul and participants Dr Tania Gardner (a physiotherapist at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney), Dr Blake Dear (Macquarie University) and Dr Nigel Armfield (University of Queensland) explored the role that SMS texting can have in the self-management of pain.

Interestingly, the forum was chaired by Dr Ali Gholamrezaei, who is also the project officer in Paul’s research group, and it was part of broader topical sessions at the conference that examined digital health technology to deliver pain treatment.

Speaking with InMotion, Paul says that as well as having the capacity to send appointment reminders and communicate behaviour change techniques, text messaging is also a quick, inexpensive and easy way to improve wellness in patients by motivating them to exercise more, lose weight, stop smoking or eat better.

It also has applications in mental health and, he says, texting has already been used widely in certain medical fields such as cardiology and the management of diabetes and with patients who have renal failure.

The use of texting as a means to communicate pain self-management strategies remains a relatively new frontier.

‘These days everybody has a phone and almost everybody has a phone that can take messages.

'But they generally don’t have a lot of health apps on those phones,’ Paul says.

‘The ability to modify text messages is much easier than having to get a graphic designer and an IT person to fix and change an app.

'And with the capabilities of multimedia messaging you can add links, GIFs and so much more.’

Paul and his team are studying the use of text messages to support people who are tapering their opioid use, the so-called legacy patients who have chronic pain and have been on long-term opioids, often at high doses.

Having published more than six papers, including one recently in Pain, the journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain, the team has found that people tapering opioids need a lot of support, and that the majority of them favour the use of text messages over apps to deliver that support.

‘We are doing a pilot study, co-designed with patients and clinicians so it’s not just academic researchers doing it.

'And we have developed a library of about 200 messages,’ Paul says.

‘In the current project we are using the best 56 of them, voted for by clinicians and consumers as being the most likely to help.

'They cover issues such as motivation to change, validation for the changes being made, education and also some pain self-management strategies.’

The team is also conducting a randomised trial where participants in the study receive twice daily text messages, in the morning and the evening, for eight weeks.

The messages mostly have a cognitive behaviour therapy focus and participants will receive maintenance text messages for up to 12 months afterwards.

Paul says text messaging in this way can work in tandem with other strategies to help patients stay on track and so far the intervention has been well received.

‘I’m one of the people recruiting patients to the study, so I’m blinded to it all, but one snippet I know is that the people who have received the intervention—all but one of them, I think—have said they wished they could continue to receive them for longer.’

- References

-

Kongsted A, Ris I, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J. Self-management at the core of back pain care: 10 key points for clinicians. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;25(4):396-406.

Darlow B, Dean S, Perry M, Mathieson F, Baxter GD, Dowell A. Easy to harm, hard to heal: patient views about the back. Spine. 2015;40(11):842-850.

Bunzli S, Smith A, Watkins R, Schütze R, O’Sullivan P. What Do People Who Score Highly on the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia Really Believe? The Clinical journal of pain. 2015;31(7):621-632.

Bernstein IA, Malik Q, Carville S, Ward S. Low back pain and sciatica: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj. 2017;356.

Moseley GL. Whole of community pain education for back pain. Why does first-line care get almost no attention and what exactly are we waiting for? Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(10):588-589.

Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: The past, present, and future. J Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.

Pate JW, Noblet T, Hush JM, et al. Exploring the concept of pain of Australian children with and without pain: qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e033199-e033199.

Leake HB, Heathcote LC, Simons LE, et al. Talking to Teens about Pain: A Modified Delphi Study of Adolescent Pain Science Education. Can J Pain. 2019;3(1):200-208.

Robinson V, King R, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. A qualitative exploration of people's experiences of pain neurophysiological education for chronic pain: The importance of relevance for the individual. Man Ther. 2016;22:56-61.

Leake HB, Moseley GL, Stanton TR, O'Hagan ET, Heathcote LC. What do patients value learning about pain? A mixed-methods survey on the relevance of target concepts after pain science education. Pain. 2021;162(10):2558-2568.

Salicath JH, Yeoh EC, Bennett MH. Epidural analgesia versus patient‐controlled intravenous analgesia for pain following intra‐abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(8).

Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG, Soop M, de Boer HD. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations: 2018. World journal of surgery. 2019 Mar;43(3):659-95.

Boden I, Peng C, Lockstone J, Reeve J, Hackett C, Anderson L, Hill C, Winzer B, Gurusinghe N, Denehy L. Validity and utility testing of a criteria-led discharge checklist to determine post-operative recovery after abdominal surgery: an international multicentre prospective cohort trial. World J Surg. 2021 Mar;45(3):719-729.

Lockstone J, Boden I, Robertson IK, Story D, Denehy L, Parry SM. Non-Invasive Positive airway Pressure thErapy to Reduce Postoperative Lung complications following Upper abdominal Surgery (NIPPER PLUS): protocol for a single-centre, pilot, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019. 9(1):e023139.

Boden I, Skinner EH, Browning L, Reeve J, Anderson L, Hill C, Robertson IK, Story D, and Denehy L. Preoperative physiotherapy for the prevention of respiratory complications after upper abdominal surgery: pragmatic, double blinded, multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018, 360, p.j5916.

Boden I, Sullivan K, Hackett C, Winzer B, Lane R, McKinnon M, Robertson I. ICEAGE (Incidence of Complications following Emergency Abdominal surgery: Get Exercising): study protocol of a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial testing physiotherapy for the prevention of complications and improved physical recovery after emergency abdominal surgery. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2018:13(1):29.

Brooks D, Parsons J, Newton J, Dear C, Silaj E, Sinclair L, Quirt J. Discharge criteria from perioperative physical therapy. Chest. 2002 Feb 1;121(2):488-94.

Harvie, D., Moseley GL. (2021). Pain and Perception: A Closer Look at Why We Hurt (book). Noigroup Publications.

Nishigami, T., Wand, B. M., Newport, R., Ratcliffe, N., Themelis, K., Moen, D., ... & Stanton, T. R. (2019). Embodying the illusion of a strong, fit back in people with chronic low back pain. A pilot proof-of-concept study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 39, 178-183.

Slater, M. (2017). Implicit learning through embodiment in immersive virtual reality. In Virtual, augmented, and mixed realities in education (pp. 19-33). Springer, Singapore.

Harvie, D. S., Rio, E., Smith, R. T., Olthof, N., & Coppieters, M. W. (2020). Virtual reality body image training for chronic low back pain: A single case report. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 13

Leake, H. B., Moseley, G. L., Stanton, T. R., O'Hagan, E. T., & Heathcote, L. C. (2021). What do patients value learning about pain? A mixed-methods survey on the relevance of target concepts after pain science education. Pain, 162(10), 2558-2568. -

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.