Addressing low pain self-efficacy in a worker with lower limb-based nociplastic dominant pain: A case study

AUSTRALIAN COLLEGE OF PHYSIOTHERAPISTS In this case study, David Elvish demonstrates how a pragmatic and comprehensive biopsychosocial model of assessment and management led to a graduated improvement in pain self-efficacy, mitigated distress and made resumption of activity possible.

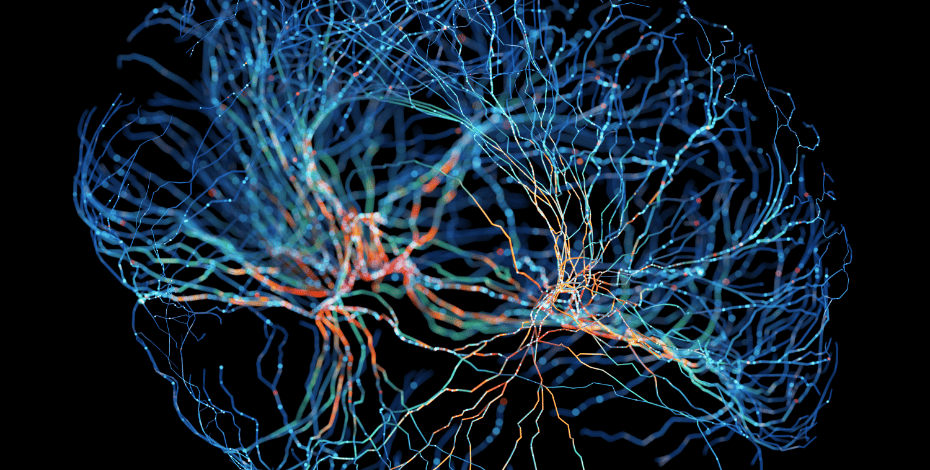

The recognition of nociplastic dominant pain (NDP) as a distinct pain type category by the International Association for the Study of Pain in 2017 conforms with the more contemporary acceptance that chronic pain is better understood as a condition of its own, rather than as a symptom of other underlying pathology or disease (Kosek et al 2021, IASP 2017).

It is estimated that 5–15 per cent of the general population experiences NDP (Fitzcharles et al 2021). While the mechanisms that underlie NDP remain incompletely understood, it is believed that augmented central nervous system nociception and sensory processing and altered nociceptive modulation play prominent roles (Fitzcharles et al 2021).

Consequently, the features associated with NDP are multifaceted and can include pain that is more widespread than or disproportionate to associated pathological findings, an unpredictable pattern of pain provocation, non-specific aggravating and relieving factors, and the additional presence of allodynia, hyperalgesia and temporal summation as well as other central nervous system- derived symptoms, such as increased sensitivity to sound, light and odours, sleep disturbances, fatigue and cognitive problems (Kosek et al 2021, Fitzcharles et al 2021, Shraim et al 2021).

The risk factors for the development of NDP also remain somewhat unclear (Kosek et al 2021). The challenge in the identification and management of NDP in clinical practice is that it often coexists in a mixed pain presentation with nociceptive and neuropathic pain (Kosek et al 2021, Fitzcharles et al 2021).

A new clinical criteria paradigm has been recently proposed to help confirm the presence of probable NDP (Kosek et al 2021).

Nociplastic-like pain features are reported to be evident in up to 46 per cent of patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) (Blikman et al 2018).

Characteristics of this subgroup with nociplastic-like features include heightened and widespread sensitivity and a greater severity of symptoms and disability, often discordant with radiographic severity (Blikman et al 2018, O’Leary et al 2018, Lluch et al 2018).

It is also understood that these patients respond less favourably to traditional OA management approaches such as physiotherapy, pharmacotherapies and surgery and have a more protracted recovery (Fingleton et al 2015, O’Leary et al 2018, Lluch et al 2018).

A comorbid association of impaired perceptual, cognitive and psychosocial factors has also been identified within this subgroup of patients (Lluch et al 2018, Moss et al 2016, Nishigami et al 2021, Urquhart et al

2015).

As a consequence of the above, a more holistic and targeted approach to assessment and treatment is strongly advocated (Lluch et al 2018, Nishigami et al 2021, Urquhart et al 2015, Mills et al 2019).

This case study highlights the importance of the identification and prioritising of multidimensional and modifiable contributing factors as part of a biopsychosocial approach, to assist in the optimal management of an NDP presentation.

Presentation

RT, a 53-year-old fitter, presented for physiotherapy assessment with a nine-month history of persisting right lower limb pain following referral from his workplace rehabilitation coordinator.

While RT had reported periodic right knee pain over the 18 months prior to this event, the onset of the more persisting symptoms was associated with standing from an extended period of kneeling, while repairing plant machinery.

The event was accepted as a workers compensation claim. The pain had been initially described as a localised pain over the medial aspect of the right knee with a clear mechanical relationship.

X-ray and MRI studies identified degenerative findings of the right knee commensurate with a grade 2 Kellgren–Lawrence classification of OA.

Following a three-month period of conservative management, RT was referred for specialist review and underwent a partial medial meniscectomy.

This was associated with a moderate reduction of the medial-based knee symptoms.

Over the next three months, RT underwent a course of postoperative physiotherapy involving a progressing exercise program.

This was associated with an initial increase of capacities and tolerances, but not associated with any further significant change to symptoms.

RT had continued with his exercise program independently since discharge from physiotherapy.

RT reported that he underwent a final review with the orthopaedic specialist at three months post-surgery, at which time he was advised that his knee had been ‘cleaned up, the best it could’, that his ongoing symptoms were likely to be due to the remaining OA in the knee and that when it was sufficiently bad enough, he would require a total knee replacement.

RT was cleared to return to full work duties and reported a gradual increase of more generalised symptoms and sensitivity over the next three months with no known associated factors.

RT now presented at nine months post-incident and six months post-surgery, with pain described as a constant ache with a varying intensity of 4–7/10 using a numerical rating scale.

Figure 1: Body chart at initial assessment.

The area of symptoms had broadened and was now present in a more generalised area both proximal and distal to the knee and over both the anterior and posterior aspects in a non-neuroanatomically plausible distribution (Figure 1).

Where previously relief had been obtained from reduced weight-bearing positions and with rest, this had diminished over time.

He reported an increased presence of sensitivity over the same area with wearing long pants, with direct pressure over the leg, with vibration from operating a forklift and with cold weather.

RT also reported a generalised feeling of perceived ‘puffiness’ around the knee. No vasomotor, sudomotor or trophic- based symptoms were reported.

The symptoms were aggravated up to 7/10 by extended standing and walking, squatting and stair use.

RT advised that he was unable to kneel due to the discomfort.

There was no specific 24-hour pain behaviour. RT now reported only limited benefit through activity limitation, use of a hot pack and periodic use of paracetamol and anti-inflammatory medication.

RT had resumed his normal roster, which involved rotating shiftwork, but reported increasing difficulties with tasks, particularly those that required sustained positioning at low levels and operating a forklift.

He also reported increasing distress about the resumption of night shift, with broken and non-restorative sleep, awake-time fatigue, difficulty maintaining concentration and concerns about putting himself

and others at risk.

He was increasingly stressed about his ability to undertake his ongoing work duties. RT advised that outside of work he was primarily ‘resting up’ for his next work shift, with minimal use of active coping strategies.

He was progressively undertaking fewer home tasks and family activities and had ceased previously valued avocational activities including dog walking, family cycling and golf with workmates.

RT did report the continuing support of and good relationships with his family, friends and work colleagues, but expressed that he was feeling like he was becoming a burden to all.

RT is a non-smoker, consumes alcohol in moderate levels on non-working days and does not take any recreational drugs.

He had increased his consumption of coffee and energy drinks, particularly during night shifts.

He was in good health with no known comorbidities and was required to undergo a yearly medical examination for his work role.

No other specific or serious contributory pathology or disease was identified on screening.

RT expressed a strong belief that the recent symptomatic deterioration was associated with degenerative changes that had progressed postoperatively, that a knee replacement was inevitable and that it was likely required within the next 12 months.

RT also expressed a moderate belief that further loaded activity and exercise-based intervention were likely to contribute to further degeneration of his knee.

He further opined that he was unsure of the role of physiotherapy considering that it could not reverse and potentially might perpetuate the progressive degenerative changes.

The completion of screening and pain questionnaires identified several elevated and likely influential psychometric findings (Table 1).

Table 1: Additional screening questionnaires and findings

Examination findings

RT was observed to mobilise with an antalgic gait, characterised by reduced weight-bearing through the right lower limb and reduced time in the stance phase.

Reduced weight-bearing through the right leg was also evident during standing (29 kilograms—36 per cent of body weight).

Right single leg balance was reduced to eight seconds (left: 30 seconds). RT demonstrated an active range of motion in non-weight-bearing with flexion to 120 degrees (left: 125 degrees) and extension to full range.

Structural testing of the knee was unremarkable.

Compressive loading of the medial tibiofemoral compartment was associated with heightened localised symptoms to 6/10.

Increased tenderness was reported over the medial joint line.

Knee and thigh girth circumference measures were comparable to the left knee with no obvious swelling/oedema present.

The presence of temporal summation and sharp, pressure and cold hyperalgesia were identified (Table 2).

No other sensorimotor deficits were determined. No other sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/oedema or motor/trophic-based signs were evident.

Grade 5/5 strength of both knee extension and flexion was present.

A modest level of hypertonicity was present in the right hamstrings, hip adductor and calf musculature.

Squatting demonstrated guarding of the knee with minimal right knee flexion beyond one-quarter range squat and weight primarily taken through the left leg (right: 23 kilograms).

Additional tolerances are recorded in Table 3.

Following additional assessment of the right lower limb and lumbopelvic regions, no other contributory factors were identified.

The chronic nociplastic pain algorithm was used to assist with determination of the presence of probable NDP.

I was able to use the algorithm to document the flow of decision-making and presence of additional features to reach the recommended level of evidence required to determine probable NDP (Kosek et al 2021).

The musculoskeletal clinical translation framework was used as the primary form of clinical reasoning (Mitchell et al 2018).

RT was provided with a diagnosis of chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain associated with OA, with associated lower limb-based NDP (Kosek et al 2021, Perrot et al 2019).

The possibility of malignancy or infection could not be excluded at this point.

It is also possible that RT had developed chronic primary musculoskeletal pain of the lower limb with no casual association with the identified knee OA (Nicholas et al 2019).

RT did not have sufficient signs and symptoms to meet the full Budapest Criteria for CRPS Type 1 (Harden et al 2010).

All findings were shared with RT to assist with his understanding of the contributing factors to his presentation.

Table 2: Clinical sensory testing

Table 3: Key assessment findings

Treatment

Using a biopsychosocial model approach to planned management, initial collaborative planning focused on strategies likely to have a relatively immediate modulating effect on the probable drivers of the distress, including low pain self-efficacy and sleep impairment (Urquhart et al 2015).

Within the treatment planning, initial patient- led goal setting was also undertaken and used as a treatment modality itself (Mills et al 2019, Rogers et al 2022).

First-line strategies included validating the current pain experience (Fitzcharles et al 2021, Edmond & Keefe 2015), developing a shift from the belief that pain is directly associated with tissue damage (Stanton et al 2020) and implementing strategies to aid more restorative sleep (Siversten et al 2015), all with the primary purpose of increasing pain self-efficacy.

Sleep was initially addressed through the cessation of night shifts, limitation of caffeine, the resumption of regular activity and the use of calming (breathing/ mindfulness) strategies (Mills et al 2019, Finan et al 2013). Initial pain science education (PSE) was focused on the contained clinical evidence of OA findings, acknowledgment of the presence of the NDP features and the likely association with more central drivers (Stanton et al 2020).

Daily activity resumption was initially focused on establishing baselines and equalising of weight- bearing with walking, sit to stand and rudimentary squatting.

A graded activity/pacing approach was then incorporated to initially establish baselines and then introduce a staged resumption of identified key activities (Antcliff et al 2021, Ferro Moura Franco et al 2021).

Supplementary PSE reflective of RT’s needs continued to be provided during further consults.

Development of an additional planned hierarchy for the resumption of family activities, playing golf and resuming house roles was also established and undertaken from consult 2 onwards.

RT experienced flares between consults 2 and 3 and 4 and 5, principally related to overdoing activities.

These served as good opportunities to additionally problem-solve likely contributing factors, to develop additional active pain coping skills and flare management strategies and to reinforce the generally benign and naturally resolving nature of flares (Dagerstedt et al 2020).

Discussions regarding the longer term resumption of night shiftwork and return to all household tasks occurred at consult 5.

By consult 6 and considering the level of skill acquisition achieved and the improved clinical picture, a joint decision was made to transition to independent management.

At consult 6, RT reported symptoms of 1–4/10, a substantive reduction of the NDP and sensitivity, that the remaining symptoms had returned to a more localised and mechanical presentation and that he had resumed most valued activities.

RT attended for six one-hour-long consults over an 11-week period with a three-month review by telehealth.

RT attended with his wife on consults 3 and 5.

Additional liaison occurred during this time with his employer on four occasions.

Discussion

The use of a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment approach (Musculoskeletal Clinical Translation Framework) enabled evaluation of the dominant pain mechanism, identification and prioritising

of multidimensional and modifiable contributing factors and a thorough understanding of RT’s beliefs regarding his pain and his recovery and management expectations (Urquhart et al 2015, Mitchell et al 2018).

It was hypothesised that the timing of the progressive development of the NDP features (more widespread pain, increased sensitivity and cognitive impairments) appeared to correlate with the deterioration of restorative sleep after the resumption of night shifts.

This in turn appeared to drive the cascade of reducing confidence to manage despite pain and greater adoption of maladaptive coping strategies (rest, activity avoidance, medication). Shiftwork, particularly night shiftwork, is associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain (Matre et al 2021).

Additional studies have demonstrated a more specific association between impaired sleep, knee symptoms and sensitivity (Mills et al 2019, Sivertsen et al 2015).

The plan for a trial withdrawal of night shifts had been discussed with RT and was supported by his employer (Cullen et al 2018).

Had the withdrawal of night shifts not been possible and/or the implementation of additional sleep strategies not been promptly associated with an improvement in restorative sleep, the need for referral to a pain medicine/sleep physician and/or clinical psychologist for a more formal assessment in sleep quality would have been considered.

It was also postulated that RT’s reduced pain self-efficacy and increasing use of maladaptive coping strategies were being driven partly by his strong pathology-oriented beliefs.

The initial PSE focused on creating an alternate narrative in which other factors (low pain self-efficacy, impaired sleep, work stress, low self-worth) were more associated with the deteriorating clinical picture, emphasising the likely benefit of implementing strategies to address these factors (Stanton et al 2020, Bunzli et al 2019, Nissen et al 2022, Lin et al 2020).

A fundamental shift in these strong beliefs occurred around consult 3 when RT started to see an association between the improving sleep and self-efficacy and a more positive clinical picture.

This led to a greater willingness to consider the potential contribution that the management of other factors might have.

Further acceptance was also achieved by engaging RT’s wife in these discussions.

The evidence suggests that PSE must be individualised and provide adequate time for discussion of complex concepts to achieve optimal benefits (Mills et al 2019, Stanton et al 2020). Beyond the PSE intervention, additional focus was directed to the strengthening of RT’s self-efficacy through the development of active pain coping skills and self-management strategies (Mills et al 2019, Degerstedt et al 2020).

Adherence to ongoing self-management post-treatment is significantly enhanced by higher self-efficacy (Degerstedt et al 2020). RT found additional mentoring through a work (and golf) colleague who was deriving benefit from a similar management approach.

The decision to use a graded activity approach rather than specific exercise was based on the lack of identified impairments of movement/control, the lack of response to previous specific exercise and the expectation that this approach would allow RT to see a direct link between expected increases of activity and progression towards achievement of the developed goals (Antcliff et al 2021).

The favourable body mass index excluded a need for additional exercise targeting weight loss (Mills et al 2019).

While there is an understanding that exercise may also contribute to central analgesic effects and a more localised cytokine response, there is at present a paucity of evidence to advocate for more specific use of therapeutic exercise/activity approaches for lower limb NDP (O’Leary et al 2018, Ferro Moura Franco et al 2021).

While the chronic probable nociplastic pain algorithm is supported by expert opinion, its clinical validity is yet to be rigorously tested, from which a more definitive NDP algorithm may be able to be established.

Expert learning for members

Additionally, because NDP has only recently been established as a distinct pain type category, substantive evidence of risk and prognostic factors and guidelines for evidence-informed care remain limited.

As such, many of the evidence-based guidelines used for my clinical decision-making have come from studies of chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain.

Despite the limitations detailed above, this case study highlights the value of prioritising a range of modifiable contributing factors as part of a biopsychosocial approach to assist the optimal management of an NDP presentation.

Click here for references.

>>David Elvish is an APA Pain Physiotherapist based in Newcastle, New South Wales. David is the managing director of Workplace Physiotherapy and a co- director of Innervate Pain Management, working within a diverse interdisciplinary team. He is currently in his second year of the registrar training program with the Australian College of Physiotherapists.

© Copyright 2025 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.