Communicating with LGBTQIA+ communities

Inclusive and respectful communication with patients and colleagues who are LGBTQIA+ is an important part of physiotherapy practice. Dr Megan Ross, Bronte Scott and Jess Hiew of the APA’s LGBTQIA+ Advisory Panel explain why and offer some tips.

What is inclusivity and why does it matter?

LGBTQIA+ inclusivity means acknowledging and respecting that diversity in sexual orientation, gender identity and innate sex characteristics is a normal part of life.

Within the physiotherapy community, the assumption that all people are heterosexual, cisgender and endosex (click here for a reminder of what this terminology means) can have a negative effect on the health and wellbeing of our LGBTQIA+ patients and colleagues.

Understanding and using the appropriate language and terminology can help to ensure that our services and organisations are inclusive and respectful of LGBTQIA+ communities.

Communication basics and avoiding assumptions

Inclusive language is language that is respectful and accurate and promotes acceptance and the value of all individuals.

It is free from words, phrases or tones that reflect or reinforce bias, prejudice, stereotypes or discrimination.

Using inclusive language puts the person first and avoids focusing on how society defines people based on characteristics.

Dr Megan Ross.

It is an easy way to facilitate respect and reciprocity and to enable safe, welcoming and meaningful conversations and interactions.

In the context of LGBTQIA+ identities, using inclusive language and avoiding assumptions about someone’s gender identity, sexual orientation or sex characteristics acknowledges the diversity of humans and respects that not everyone will define themselves in the same way.

When you communicate with anyone, it is important to recognise and leave space for human complexity, intersectionality and diversity and to avoid making assumptions.

Heteronormative assumptions are assumptions about someone’s sexual orientation—the idea that heterosexuality is the preferred, default or normal mode of sexual orientation, which also assumes the gender binary (that sexual relationships are between one man and one woman).

Cisnormative assumptions are assumptions about someone’s gender identity—the idea that being cisgender is the norm (that gender identity always aligns with sex assigned at birth) and should be privileged over any other gender identity.

Endonormative assumptions are assumptions about someone’s innate sex characteristics (the chromosomes, hormones, genitals and other anatomy that someone is born with)—the idea that physical sex characteristics match what is expected for female or male bodies.

The impact of assumptions and misgendering

The impacts of making assumptions, misgendering and deadnaming in healthcare go beyond damaging the therapeutic relationship in question.

Actual (or fear of) discrimination, based on past experiences (personal or institutional), prevents many individuals who identify as LGBTQIA+ from seeking medical care.

When health professionals hold and/or demonstrate heteronormative attitudes, outcomes can include delaying medical care, lack of disclosure (even when disclosure may be important for therapy) and a lack of targeted health promotion and care.

Putting it into practice

Bronte Scott.

When meeting someone for the first time, avoid making assumptions about gender identity, sexual orientation or sex characteristics based on their physical appearance.

This is never okay.

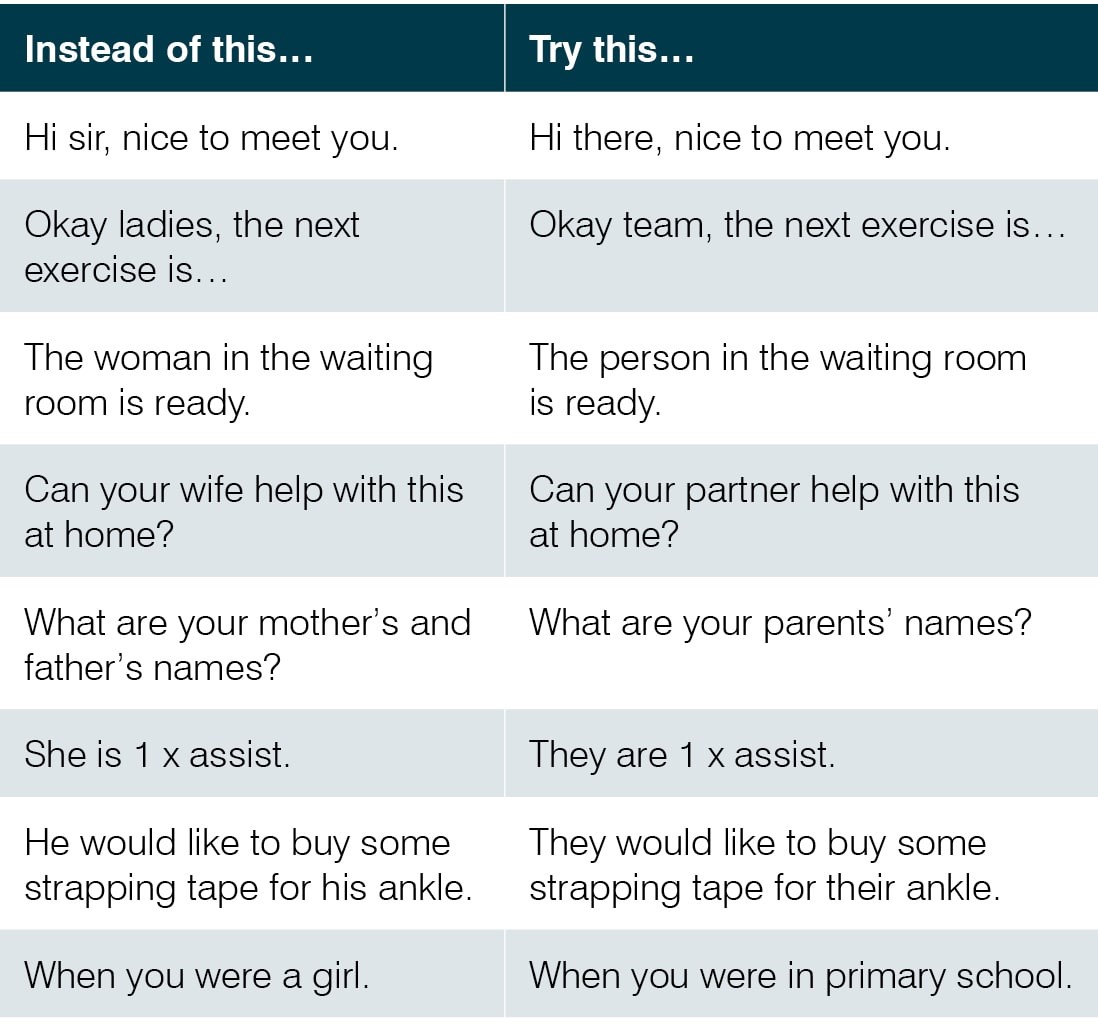

To be inclusive of all gender identities, it is best practice to use gender-neutral terms, or avoid gendered language altogether, until you are aware of someone’s specific gender identity.

This also applies to the gender of someone’s partner and diverse family make-up.

If their sexual orientation is unknown, it is best practice to use gender-neutral terminology such as ‘partner’ and to use terms like ‘parent’ rather than ‘mother’ and ‘father’.

Introducing yourself using your pronouns and including space for pronouns on intake forms are two simple ways to give others the opportunity to share their pronouns with you.

When you are referring to someone and they have shared their pronouns or that they are trans, genderfluid, non-binary or Two-Spirit, be sensitive to their stated name, pronouns and gender.

It is discrimination to misgender or deadname someone (to use their gender or name assigned at birth when they have explicitly indicated their name and pronouns).

But... when is it appropriate to ask specific questions about gender, sexual orientation or sex characteristics?

Before asking personal questions about gender identity, sexual orientation and/or sex characteristics, ask yourself, ‘Is this information relevant to this patient’s care?’

If it isn’t, then beyond asking for pronouns and preferred terms for specific anatomy, intrusive or inappropriate questions should be avoided.

‘Over curiosity’ describes health practitioners’ intrusive and invasive questions and examinations that are irrelevant to the medical care of people who are trans or gender-diverse or those who have intersex variations.

At times, this information is important and contextually relevant (for example, asking about surgical history during a pelvic health appointment or for scar tissue management).

To make these conversations more comfortable:

- use inclusive language

- explain why you need to ask for this information and how it will help their management

- ask what words they would like you to use for specific anatomy

- ensure confidentiality and privacy

- manage your reactions.

What if I make a mistake?

Many of us grew up in environments where cisgender, binary and heteronormative attitudes predominated and it is likely that we might make mistakes when we are learning something new.

It is okay to make honest mistakes when you are learning, but it is harmful to be defensive, deflect accountability and not learn from them.

We know that using the correct pronouns is inclusive and respectful and will help a person feel welcome and accepted.

So, what happens when we make a mistake?

Accidentally using the wrong pronouns may make someone feel rejected and not accepted and can have an adverse impact on their mental health.

It is likely to be detrimental to the therapeutic alliance if not managed in a timely and appropriate way.

Deliberately not using correct pronouns (or misgendering) is overt discrimination and is likely to be harmful and to have a negative impact on mental health and wellbeing.

As well as damaging the therapeutic alliance, this may also trigger shame, anger and other emotions, stemming from previous negative experiences personally or with institutions (social, cultural or religious).

Appropriately responding when you make a mistake is vital.

Focus on quickly acknowledging and correcting the mistake without drawing a lot of attention to it and then commit to doing better next time.

Jess Hiew.

Voicing your commitment to the learning process can re-instil trust in the relationship and avoids putting the onus on the individual to correct you.

And then, of course, make sure that you actually practise so you are less likely to repeat your mistake.

If you do make a mistake, don’t panic.

Remember that this is not about you, so try not to prioritise your feelings or ego, make excuses or deflect accountability.

Although the impact of assumptions and misgendering can be significant (even when accidental), try not to be overly apologetic and draw attention to the mistake by making a drawn-out apology.

It is not the person’s responsibility to make you feel better, so please don’t expect to be told it is okay.

It is not appropriate to emphasise how much effort is required to change or pretend it didn’t happen.

Ignoring your mistake tells the person that you don’t recognise their identity as authentic, which can be harmful.

A simple acknowledgement of your mistake and a genuine openness to learning and changing can go a long way.

If you make a mistake, pause, acknowledge and apologise.

Correct the mistake as quickly as possible, say it again correctly and move on.

Commit to doing better and practise.

‘I’m sorry. They are on their way. I will do better next time.’

Using inclusive language and being respectful of diverse identities is relevant for interactions with all individuals.

Click here for an upcoming course on intersex awareness.

>> Dr Megan Ross is a physiotherapist and postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Queensland. Megan is a member of the Queensland branch of the APA’s Musculoskeletal national group and is a UQ Ally, serving on the UQ Ally Action Committee. She leads a program of research in the LGBTQIA+ space, including patient and physiotherapist experiences within the profession.

>> Bronte Scott is a physiotherapist at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, working in the acute inpatient setting, and an APA Cardiorespiratory national group member. As a lesbian woman of faith, Bronte has lived experience of the exclusion too often encountered by the LGBTQIA+ community. Bronte has advocated in national media for LGBTQIA+ representation and rights.

>> Jess Hiew is a physiotherapist and business owner and has a Master of Physiotherapy from the University of Canberra. She currently sits on the Diversity and Inclusion board at Kieser Australia and is a member of the GLOBE LGBTQIA+ business networking association, advocating for LGBTQIA+ change in private practice.

© Copyright 2024 by Australian Physiotherapy Association. All rights reserved.